Atlas Displaced

Searching for surviving pieces of a unique 1874 San Francisco building.

On western shore rough and bestial,

Iron Atlas bore a sphere celestial.

Freight of earth belied grace,

Conspired, post fire, to Atlas displace.

All the office workers stayed home at the start of the pandemic and they don’t want to come back to their cubicles or trendy open-floor plans. The shady streets of the Financial District are quiet. In 2023, San Francisco doesn’t know what to do with its downtown.

In the 1950s and 1960s, San Francisco did know what it wanted to do with its downtown: tear down the old buildings and build big new office towers (which now stand empty).

One of the lost buildings during the “Manhattanization” of the Financial District survived the April 1906 earthquake and fire when most everything else crumbled and burned. What was its secret super-power? A cast iron facade and an entry supported by Greek titans.

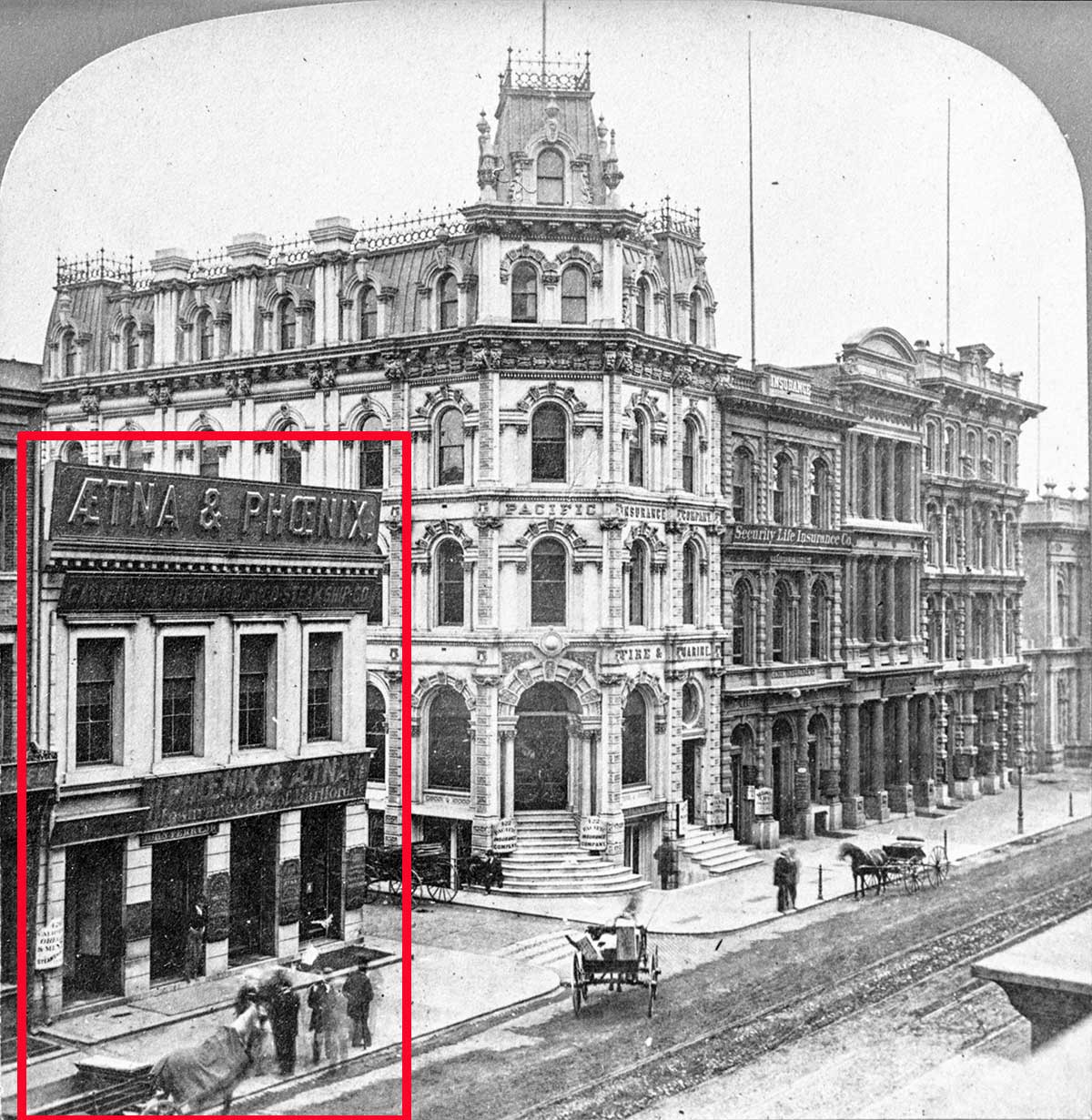

In 1873-1874, the London and San Francisco Bank constructed new headquarters on the northwest corner of California and Leidesdorff Streets. The three-story structure fit right in among a row of banks and insurance companies designed in Baroque and Classical Revival styles. In 1870s San Francisco you didn’t deposit money with a firm unless the building looked like a calcified French pastry or a Roman Temple. Take a look at the neighbors:

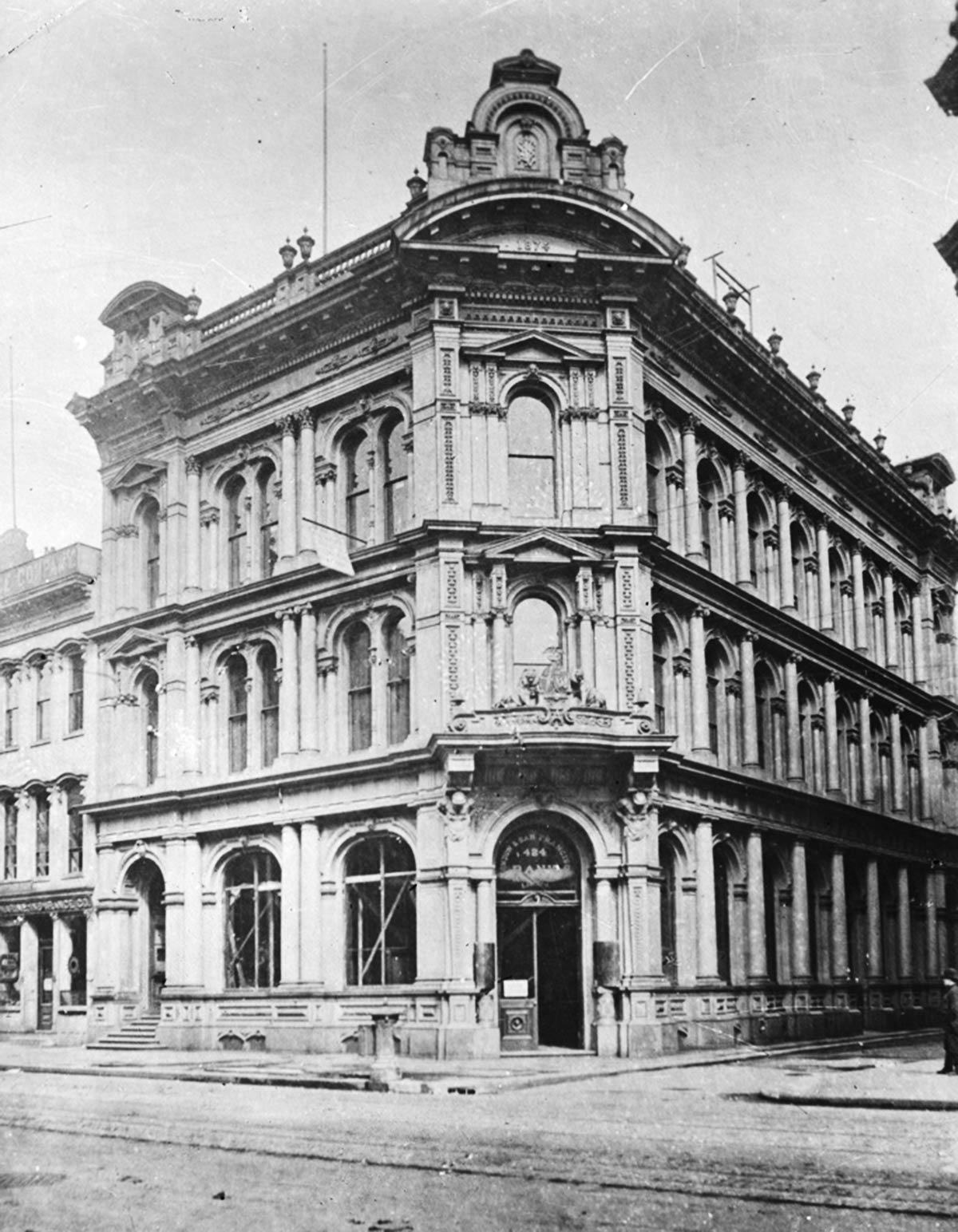

Architect David Farquaharson (a great name I recommend you chant aloud throughout the day) threw the Classical Revival kitchen sink at the fairly modest-sized headquarters of the London and San Francisco Bank: columns, colonnettes, pediments, arches, animals, shields, and every classic order of architecture were represented. The exterior had Roman Doric details on the first floor, Ionic on the second, and Corinthian on the third. Two caryatids of Atlas, the Greek Titan condemned to hold up the heavens, supported the corner entry portal.

Either in response to the town’s frequent fires or to project an aura of invincibility—good for a bank—the facade was cast iron, made by Hinckley & Co.’s Fulton Foundry on Fremont Street. Craftsmen at the foundry first designed the sections in clay to create molds. Molten iron was poured into the molds, producing 10- to 12-foot segments averaging ½ -inch in thickness. These were then carted by dray animals six blocks to the job site where the sections were bolted together on the building.

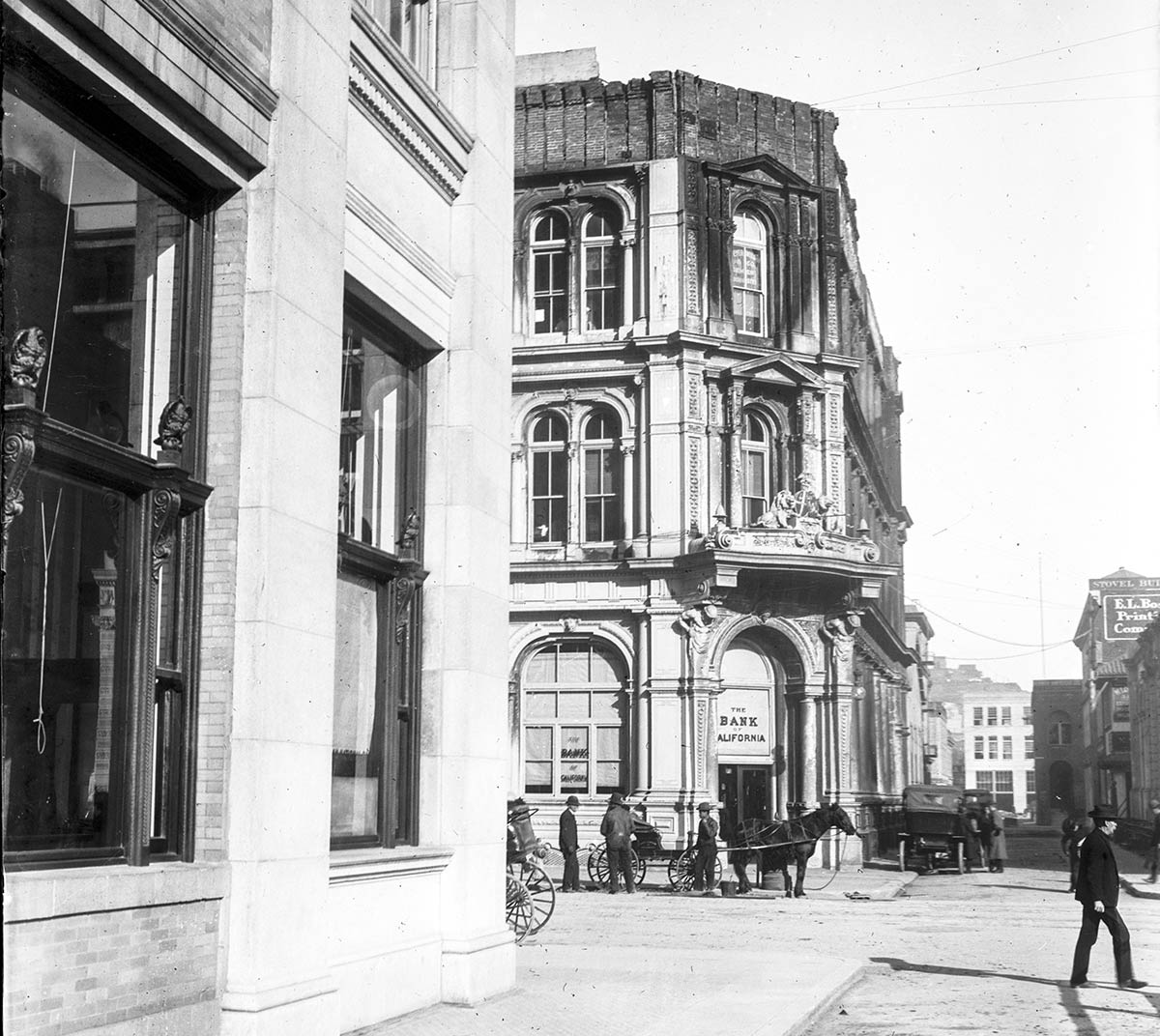

The London and San Francisco Bank was taken over by the Bank of California in 1905. Massive fires started by the April 18, 1906 earthquake gutted the interior of 450 California Street the following year. But when the streets cooled, the cast iron front, the vaults, and most of the walls remained intact.

Business resumed in “Old Ironsides” just a month after the disaster, albeit in chaotic fashion:

“The carpenters are still at work in the banking room and on the floors above and the banging of hammers and the rough rasping of saws rise above the clinking of coins and the words of the bankers. The tellers stand at wooden counters, undivided by partitions. The rough and ready aspect of the bank in its new quarters on the first day of its reoccupancy was like that of a boom town on the frontier.”

Legendary architect Willis Polk supervised the restoration. He gave the interior a lush treatment of marble and bronze, a coffered ornamental ceiling, and a new elevator, but he respected the original iron facade. His added attic story with angels, wreaths, and balustrade complimented rather than overwhelmed the 1874 design.

Banks merged and consolidated throughout the 20th century. Over the next 50 years, 450 California Street was used by the Bank of California, San Francisco National Bank, the Canadian Bank of Commerce, the American Trust Company, and then, finally, Wells Fargo Bank.

In 1959, the Atlas Twins, having withstood the great fire of 1906 and all the corporate change-overs, finally succumbed to Yes-in-my-Downtowners (YIMDYs?) when Wells Fargo decided to build its new modern headquarters on the site.

The elegant facade was recognized as “possibly the most elaborate cast iron front in existence,” and worthy of preservation. But, in 1959, preservation meant it should be ripped off the building and put in a museum somewhere, instead of enjoyed by the public on the corner where it had been for more than 80 years.

According to contemporary newspaper articles, the San Francisco Maritime Museum Association took 450 California Street’s Atlas-enhanced entryway.

In the 1950s, the Maritime Museum was grabbing lots of old stuff for its Aquatic Park plans. The original vision was grander than the Hyde Street Pier and Maritime Museum of today’s San Francisco Maritime National Historic Park. In addition to square-riggers and lumber schooners, “Project X” was to have retired railroad rolling stock and a main street of recycled Victorian structures—sort of a permanent and high-minded Renaissance Fair, but as a Gold Rush seaport.

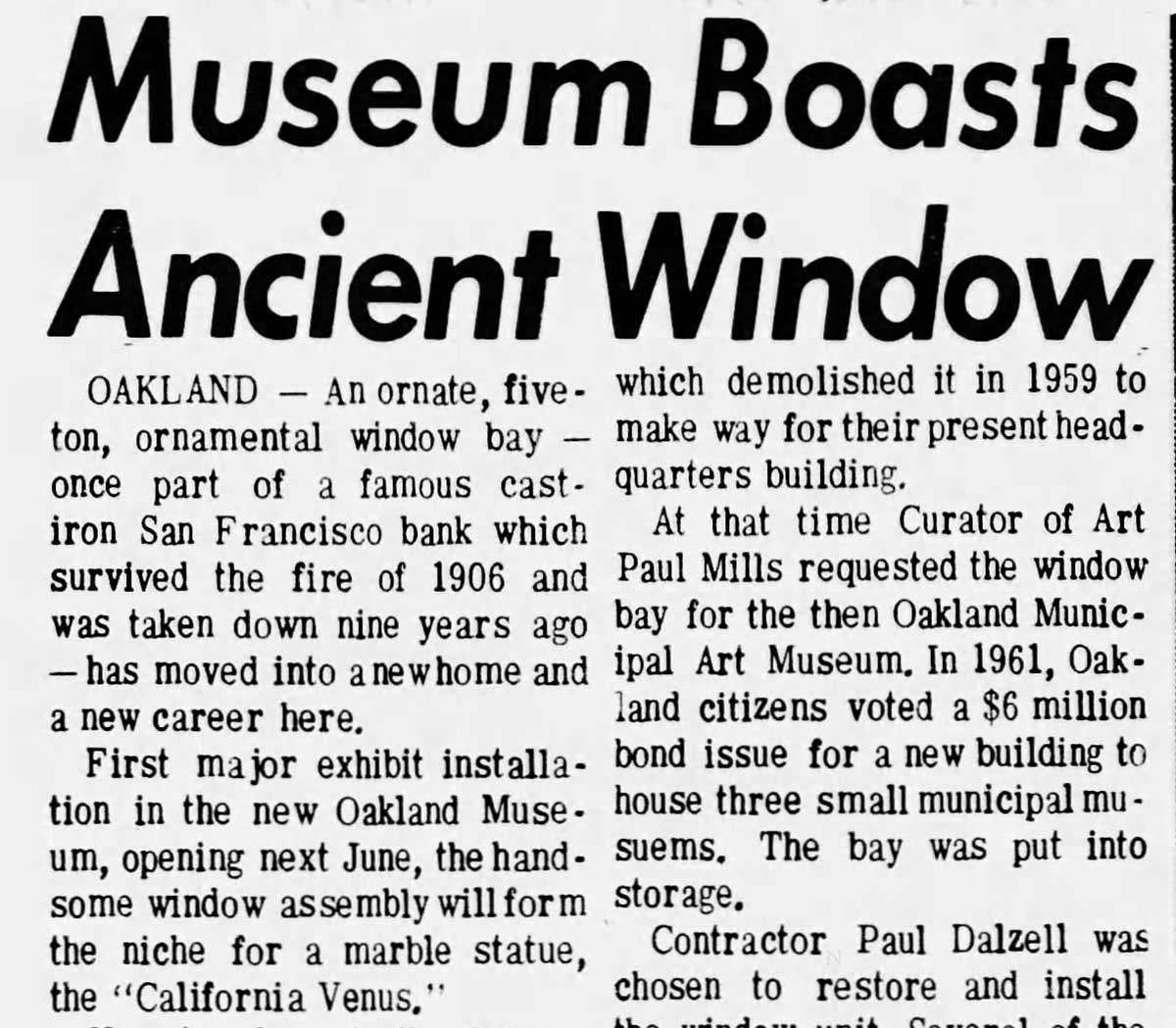

The Oakland Museum definitely claimed the massive window surround of the first story above the Atlas entryway. Ten years later, that window frame returned to public view.

These were the days when history museums tended to an attitude of more-the-better, giving many the appearance of artistically-lit used furniture stores. In 1969, when the Oakland Museum of California opened beside Lake Merritt, the cast-iron bank window was used in the Gallery of California Art to frame a “California Venus” marble sculpture.

Since then? Maybe I missed it still on display? The folks at the Oakland Museum are looking around the warehouse for me…

As for the entryway, I’ve reached out to the Maritime Museum to see if it has any record of even accepting it in 1959. No word yet.

If they still exist, perhaps the Atlas Twins can find a new home downtown. A bit of mythos may please the gods and be just what San Francisco’s Financial District needs to turn things around.

Woody Beer and Coffee Fund

Christine G. bought my coffee this week. She is a gem and, dare I say it, a National Treasure. As she is a docent in the Presidio, it was fitting I drank my java chatting with super-duper “Friend of Woody” Peter F. just off the parade grounds. (Christine, when are you free for a sip and sit?)

Thanks to all who keep sociability (and me) well-lubricated. Feel free to join the party and let me know when you can have a drink!

Sources

“Valuable Purchase,” San Francisco Examiner, August 9, 1872, pg. 3.

“Commercial Banks Open Doors to Calm Public,” San Francisco Call, May 22, 1906, pg. 1.

“In Permanent Home,” San Francisco Call, July 6, 1909, pg. 18.

“City Gets Unique Window,” Oakland Tribune, August 5, 1959, pg. 12.

“Oakland Bound,” Oakland Tribune, August 7, 1959, pg. 13.

“Museum Ironwork—a First and Last,” Oakland Tribune, November 20, 1968, pg. 40.

“Museum Boasts Ancient Window,” Napa Register, December 7, 1968, pg. 6D.