Captive Airship

How did George R. Lawrence take his amazing aerial panoramas after the 1906 earthquake?

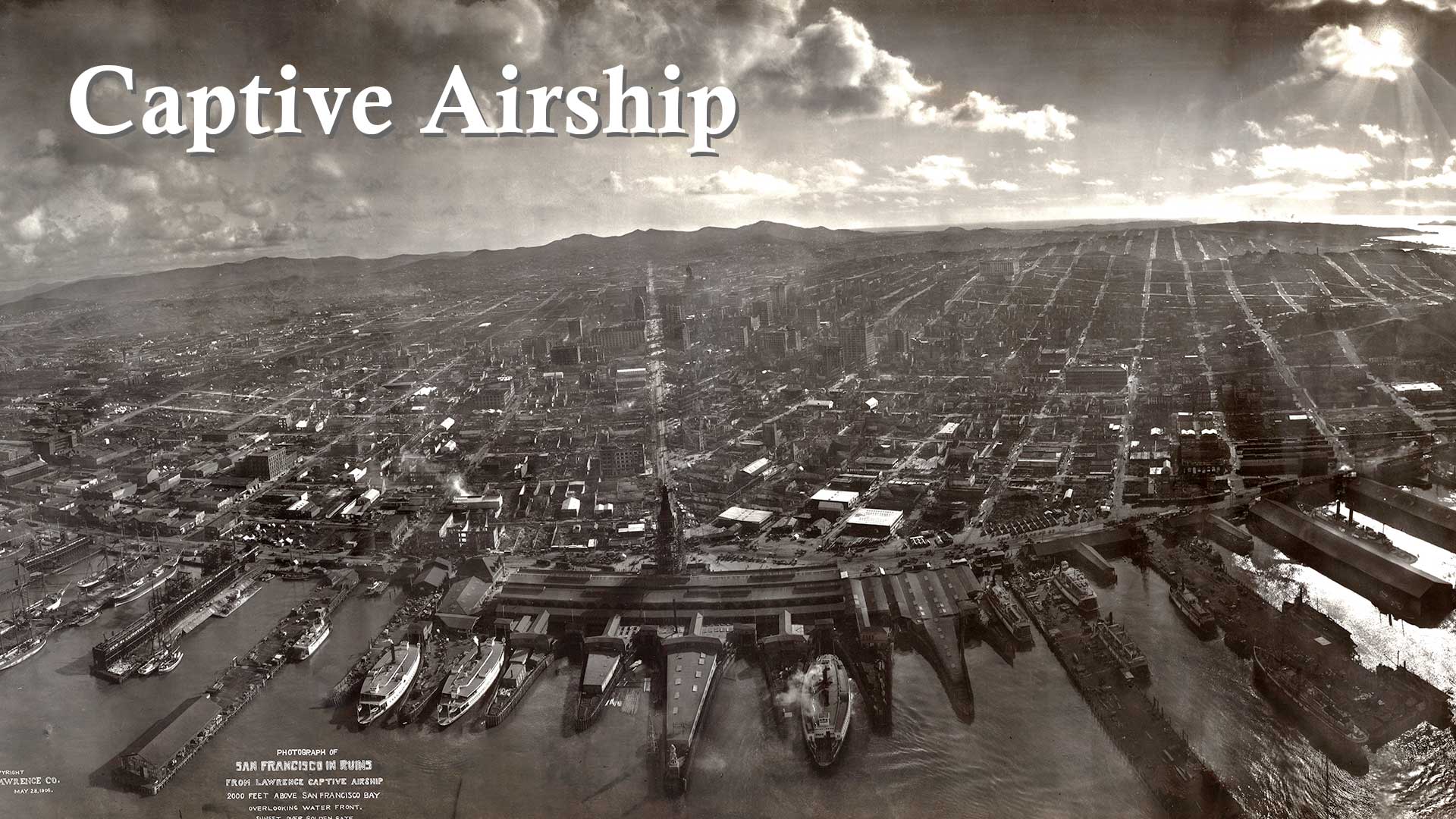

Tourists from Italy were admiring one of two aerial panoramas we have framed at the Haas-Lilienthal House. Taken by George R. Lawrence one month after the 1906 earthquake and fire, each is a different wide-angle view of a charred landscape, a gridded city of bones.

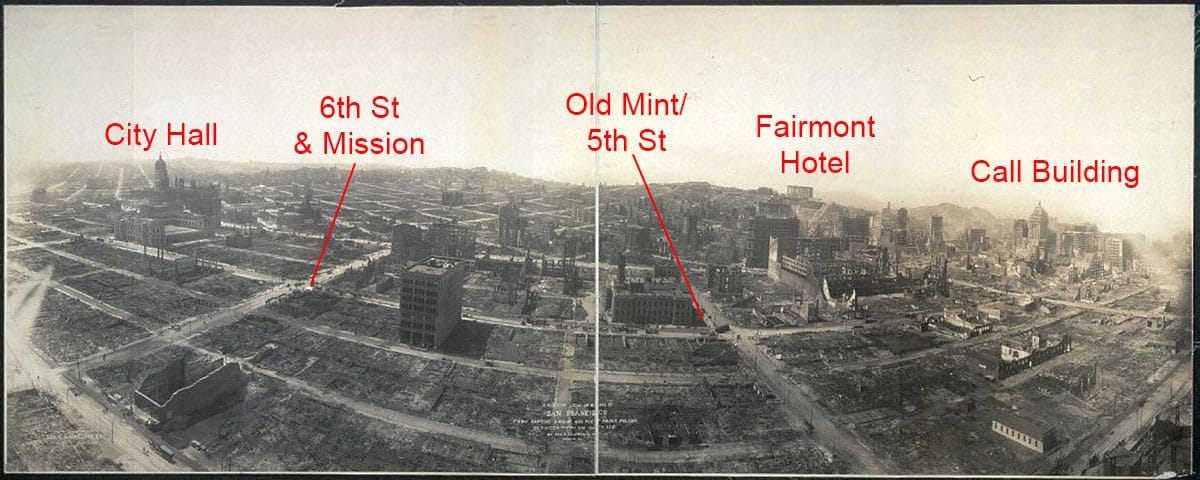

Trying to be the helpful host, I identified some visible San Francisco landmarks. There aren’t many to choose from. The destruction of downtown was almost total.

The clarity of the image is remarkable. You can see people walking, wagons on the move, and crowded streetcars put back in service just a couple of days before the photograph:

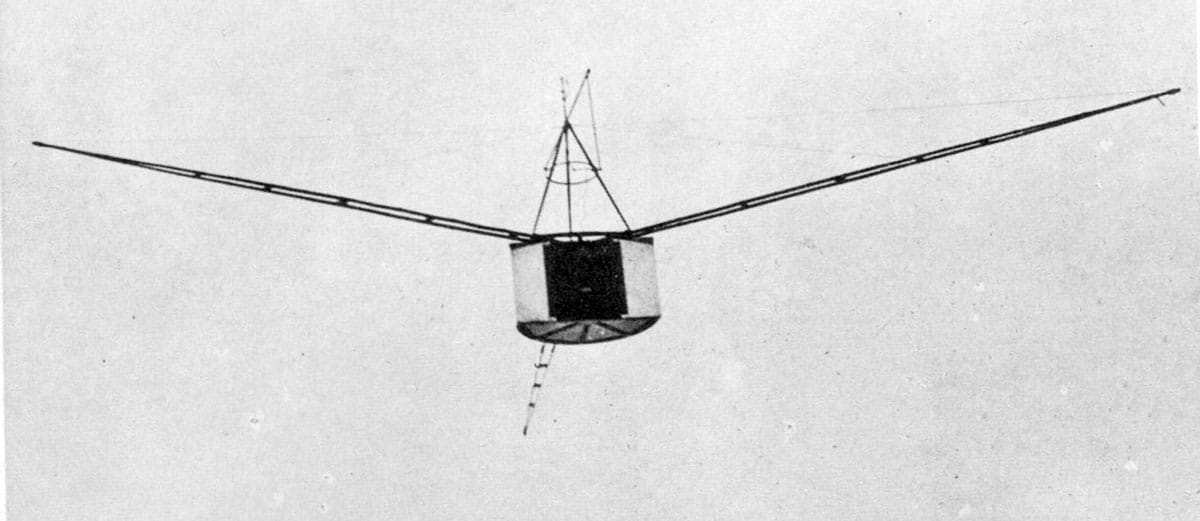

One of the visitors asked, amazed, if the view was taken from an airplane. I noted the caption printed on the photo that it was snapped from “captive airship.”

The airship was not an airplane—the Wright Brothers had gone on their famous flight less than three years before the disaster—and it certainly wasn’t a UFO.

I glibly told them captive airship meant an unmanned balloon and that the exposure had been tripped from the ground via a long wire.

Coincidentally, a week later I was writing the description of that famous photograph. (We have a version of it in our upcoming gala’s silent auction. You can bid on it here!)

I paused typing “captive airship,” bothered that maybe my facts weren’t right about that balloon.

They weren’t.

The Hitherto Impossible in Photography is Our Specialty

George R. Lawrence was a self-taught photographer and inventor. In the 1890s he advanced flash technology, tinkering with the powders to produce brighter light, and introduced electrical charges to synchronize flashes. He was an expert commercial photographer for large group shots and wide views of baseball games, presidential parades, convention dinners, and horse races.

Nowadays our phones can pan over wide scenes and software can stitch together multiple shots, but at the turn of the century you needed a mad-genius professional like Lawrence.

Negatives were cumbersome fragile sheets of glass that had to be treated with chemicals before being exposed to light at just the right moment for just the right length of time.

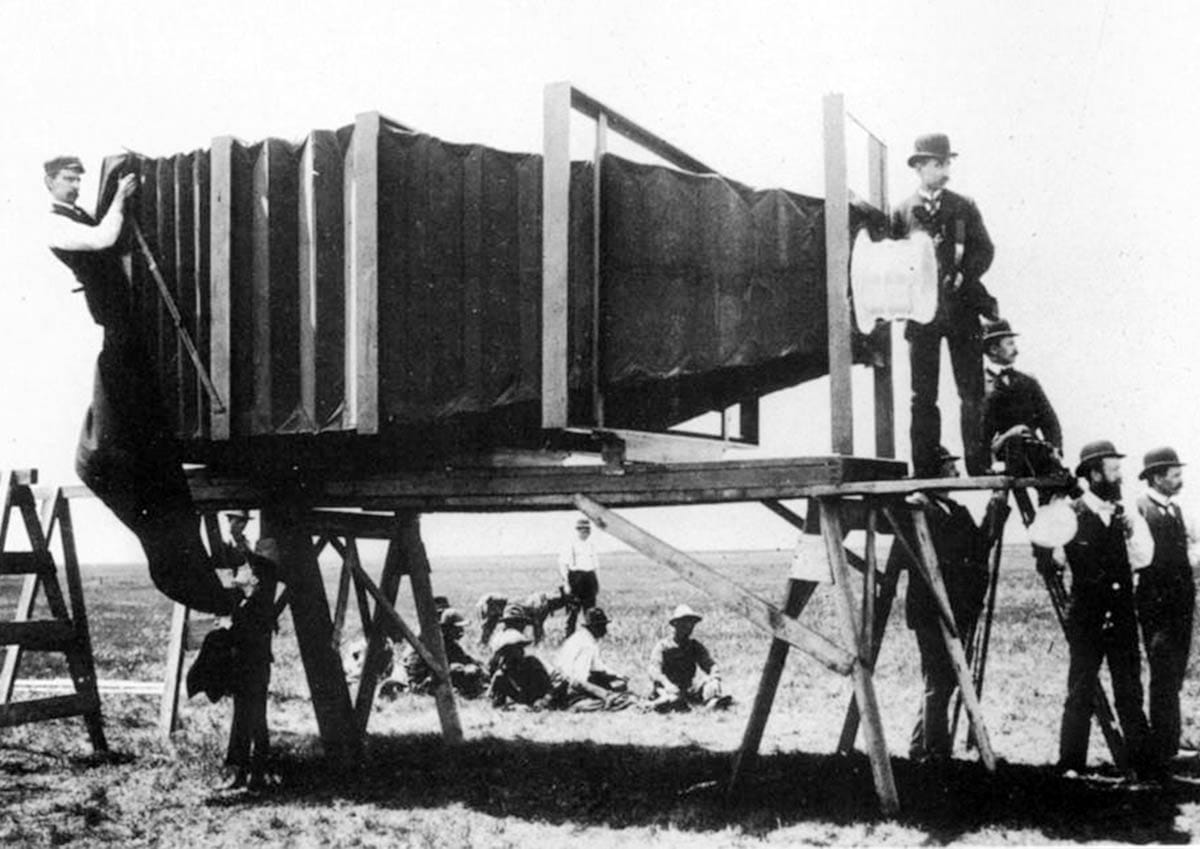

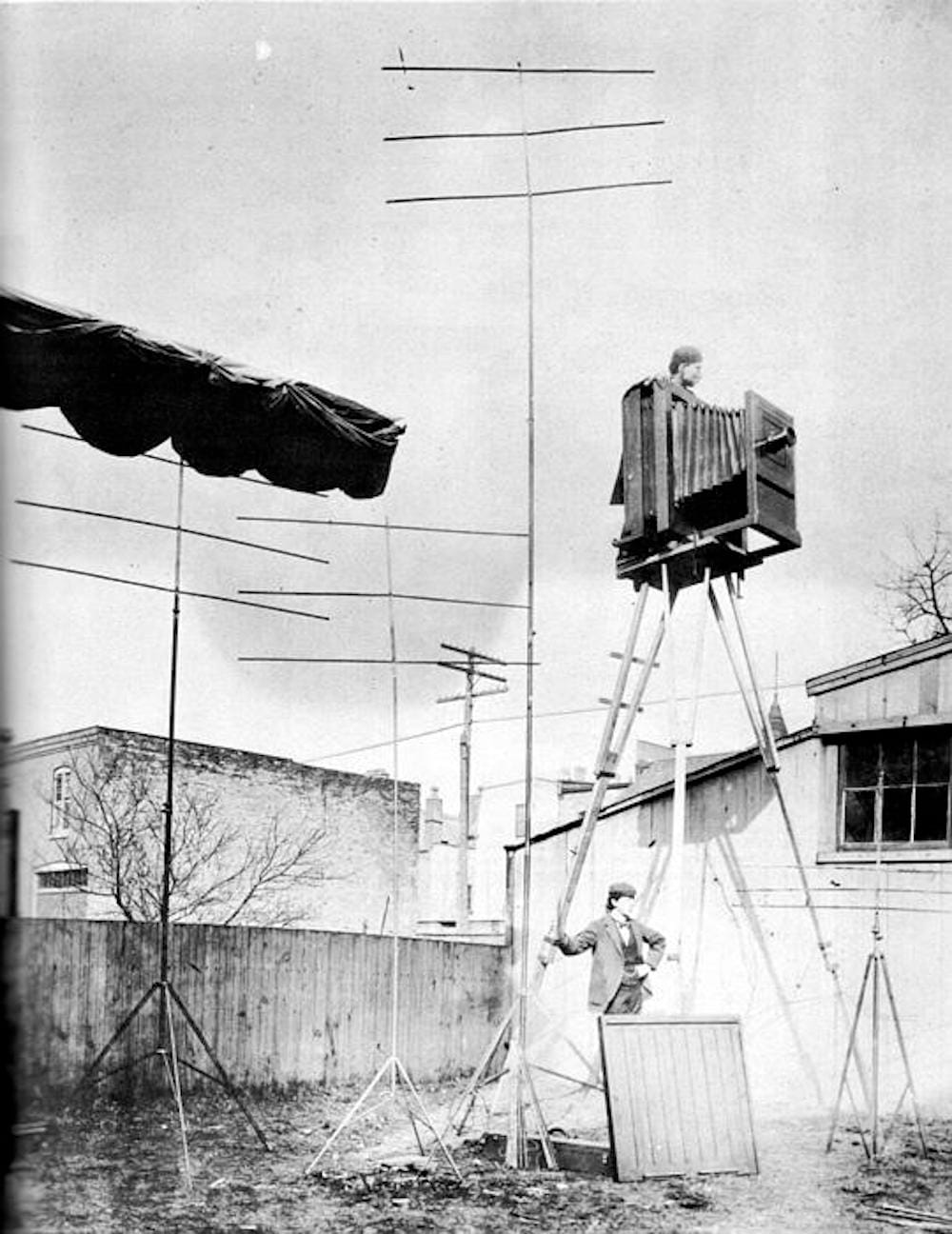

A larger negative produced a larger print. If you wanted a clear and elevated panorama of 300 Masons at their annual picnic, you needed a big negative, a big camera, and maybe a big tripod.

With the motto “The Hitherto Impossible in Photography is Our Specialty,” Lawrence was up for just about any photographic challenge.

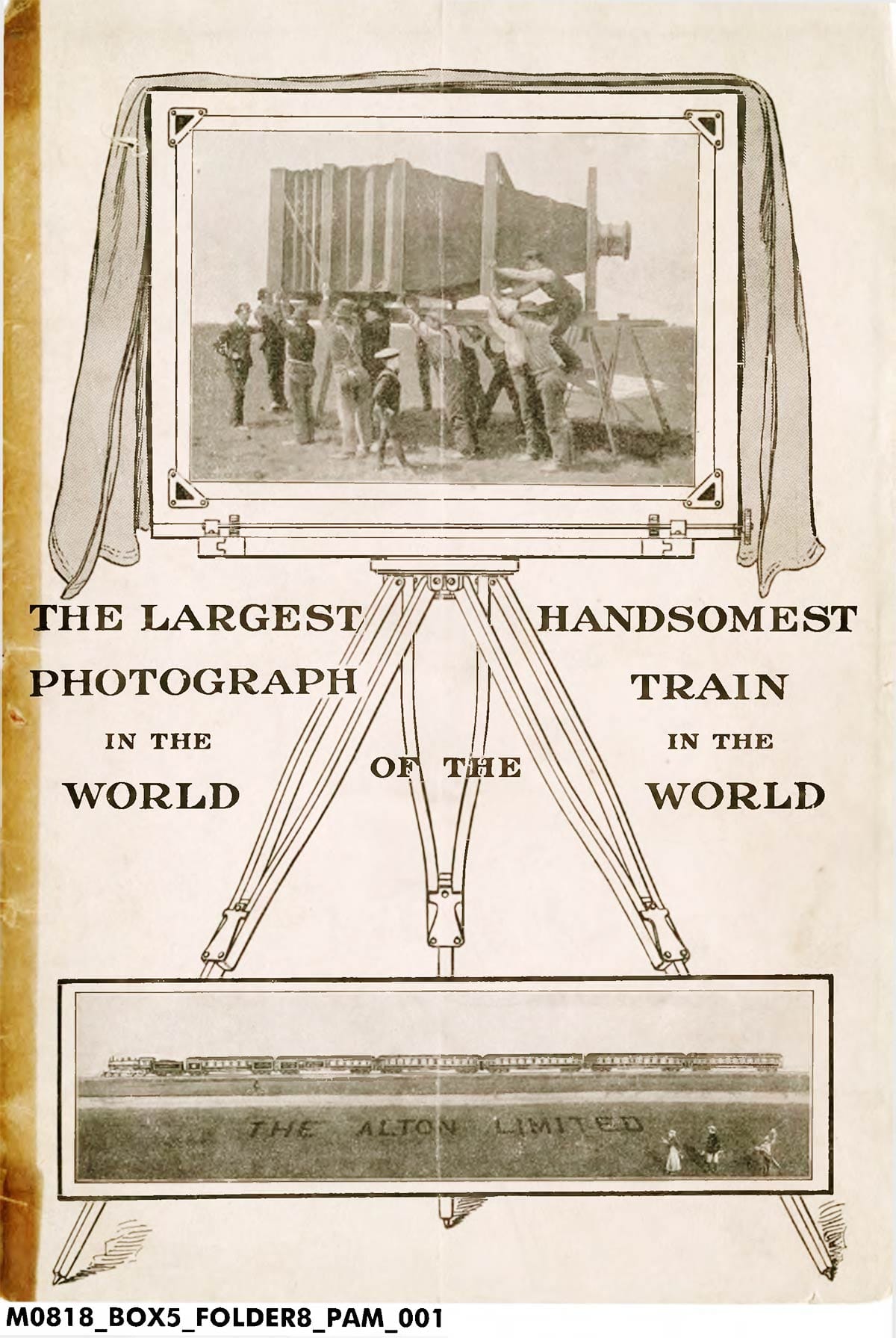

In 1900, the Chicago and Alton Railway wanted a publicity photo for its new “Alton Limited” train running between St. Louis and Chicago.

To ensure “absolute truthfulness of perspective,” Lawrence designed the largest camera in the world so he could capture the locomotive and six cars—524 feet long—in one clear shot from a quarter of a mile away.

The camera weighed 900 pounds. The glass negative and its plate holder added 500 pounds. The one-shot-only contraption produced a print 4 ½ by 8 feet in size.

Lawrence captured some of his big group scenes and vistas by constructing tripod towers for his cameras, then moved on to “birds-eye views” taken from hydrogen balloons.

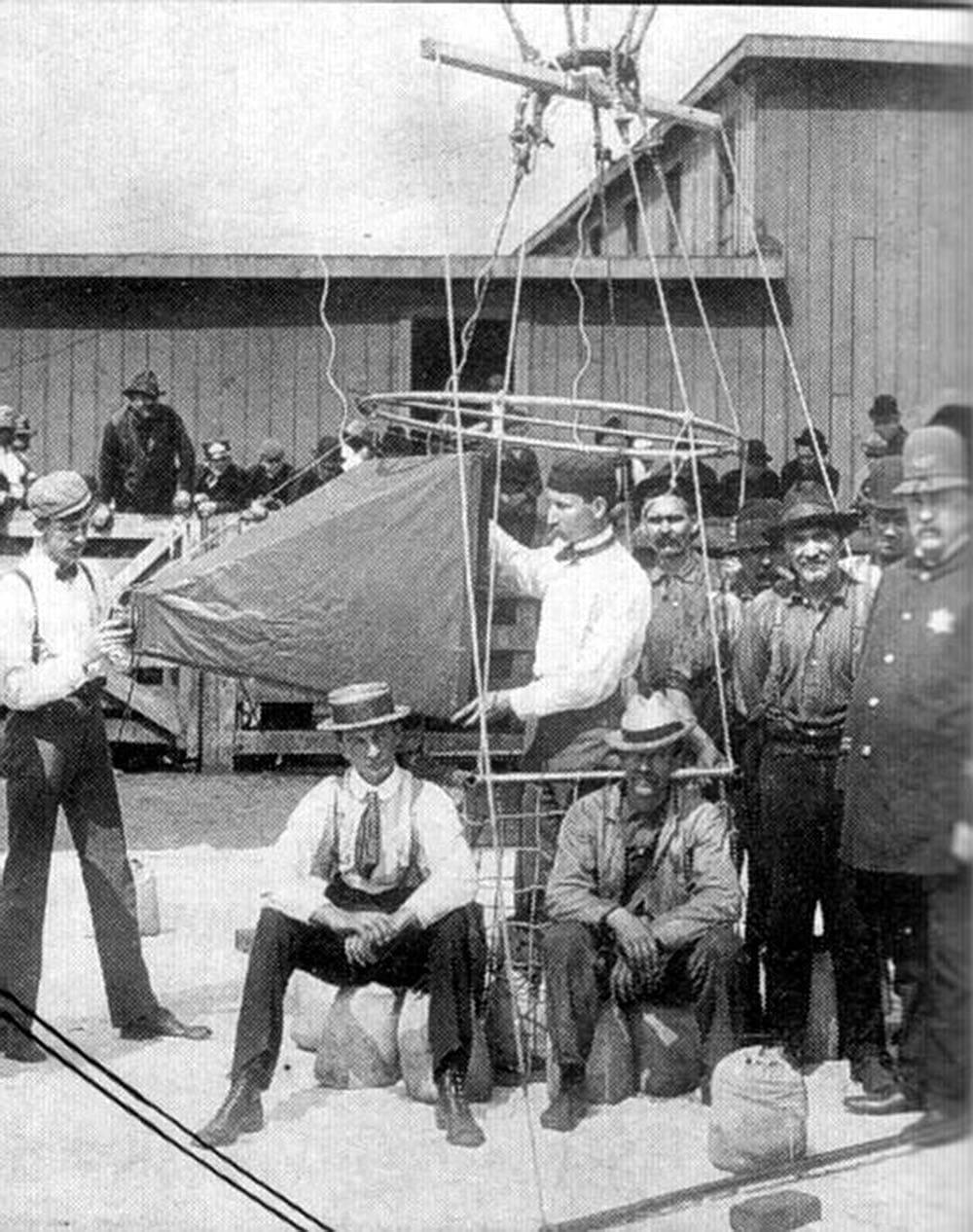

After a couple of balloon mishaps almost killed him (they happened often in the 19th century), the resourceful photographer invented a way of getting his camera up in the air without him.

Kites Away

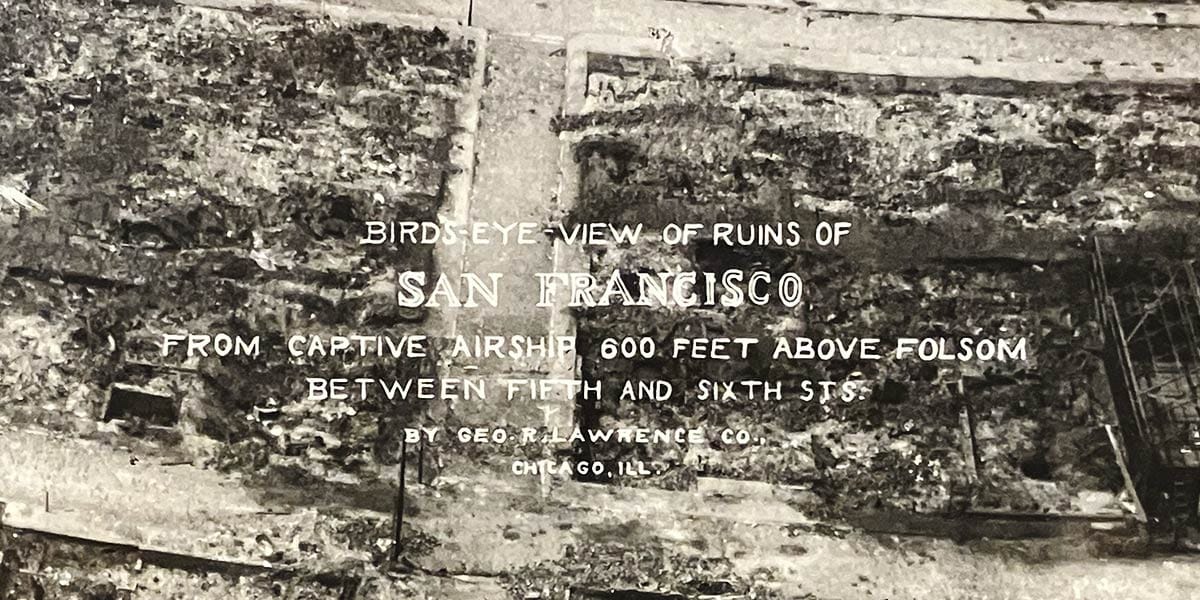

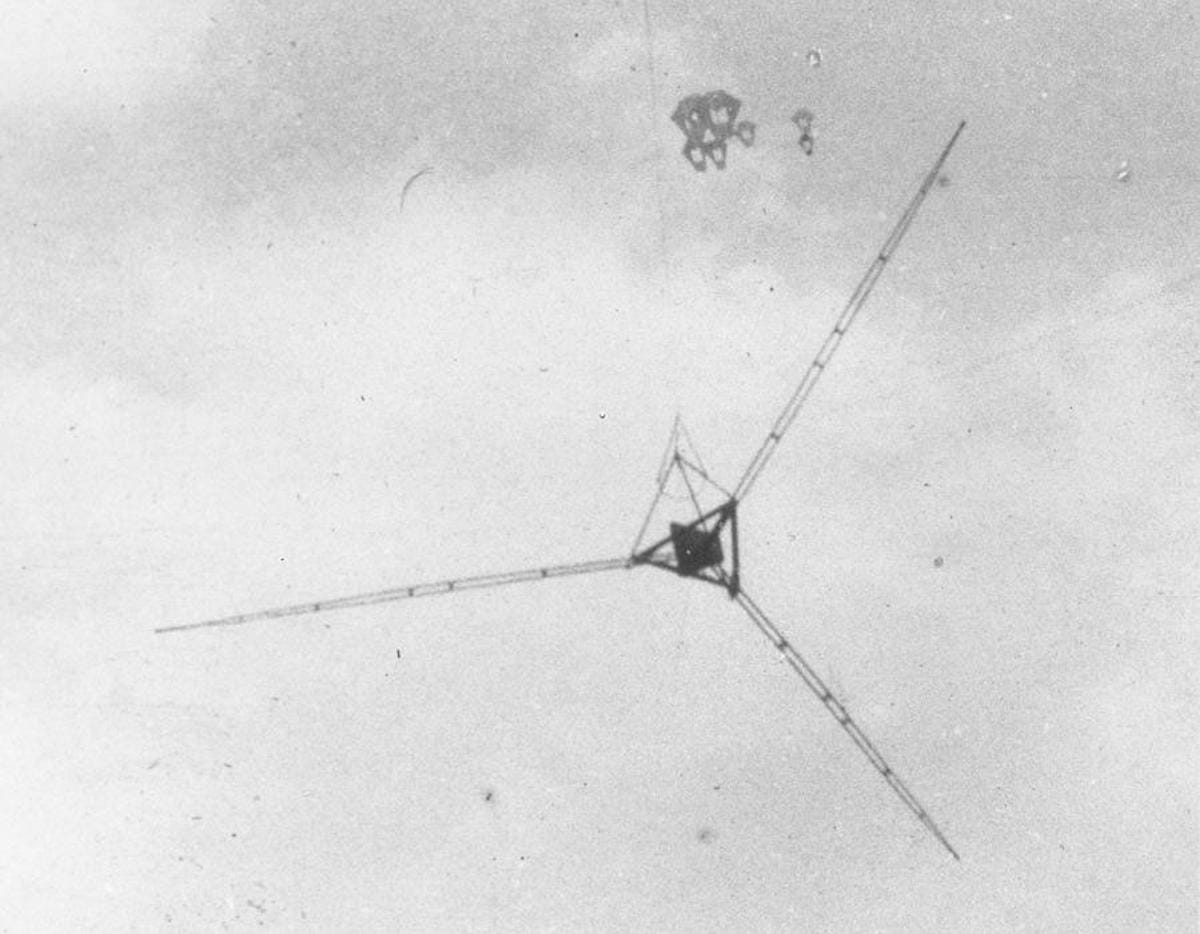

Working off a patented technology designed to fly promotional banners (advertising has always been fruitful field for American ingenuity), Lawrence started sending cameras aloft under a train of kites.

Cameras steadied by cords, bamboo sticks and lead weights had their shutters tripped hundreds of feet in the air by electrical current through insulated wires.

This was the “captive airship.”

Managing wind, angles, and technology must have taken lots of trial and error. Instead of glass, Lawrence used celluloid-film plates, but his flying cameras still weighed close to 50 pounds each.

In 1905, Lawrence pitched his invention as an aerial reconnaissance tool for the US Navy (contracts from the military have always been a fruitful field for American ingenuity). He demonstrated his kite-camera technology on the deck the USS Maine, and while impressed, the Navy decided to pass.

Then a chance in a lifetime came along in April 1906 when the city of San Francisco shook and burned. Lawrence packed his kites and headed west with a team to document the carnage.

San Francisco in Ruins

When Lawrence arrived in May 1906 he wasn’t alone.

Photographers swarmed to record the devastation (and sell prints...disasters have always been an inspiration for American ingenuity). They lugged cameras up every hilltop, climbed the damaged Ferry Building, and scaled the burned-out St. Francis Hotel to get elevated views of the ruinous landscape.

Only Lawrence, however, had a captive airship.

At the Haas-Lilienthal House we have two of Lawrence’s views, both with a wide-angle perspective of about 130 degrees (his film was fitted over a curved box). One is taken 2,000 feet above the bay looking west past unburned piers and the Ferry Building up Market Street. The other is above the South of Market area looking north.

Just one of the massive contact prints, 47-inches by 19-inches each, would set you back $125 in 1906, an unbelievable $3,500 in 2024 dollars. Lawrence made a reported $15,000 in sales, half-a-million bucks today.

In the next few years he was commissioned to take his airship cameras to factory complexes, railroad yards, and small towns proud to show off their growth with an aerial panoramic photo. None of these ventures matched the monetary success of his San Francisco-after-the-disaster shots.

Great thanks to Simon Baker, the expert on Lawrence for more than 40 years, for his research and articles.

Woody Beer and Coffee Fund

Thanks to the Friends of Woody (F.O.W.) and the Very Good Acquaintances of Woody (V.G.A.O.W?) for all the support.

The Friends fire up my motivation machine to write one of these each weekend (although you get it on Wednesday), which feeds my soul and gets me to stop thinking about nonprofit compliance documents and why stupid banks are so stupid. Both FOW and VGAOW toss occasional bucks in the Woody Beer and Coffee Fund, which slakes my thirst and makes sure I don’t stay home grumbling about being an old man.

Yer all swell and deserve free hot chocolate and biscuits, which I am happy to provide. When are you free?