Carville-by-the-Sea in 10 Slides

San Francisco's bygone bohemian community made of recycled transit cars at Ocean Beach.

Video? Yes, video! Or you can keep scrolling and read like people did in caveman days.

This San Francisco Story is how a unique community sprouted out of the sand dunes of Ocean Beach in the 1890s, the fin de siècle, where bohemians used old transit cars as clubhouses, restaurants, and rendezvous of assignation. In just ten slides, this is the San Francisco Story of Carville-by-the-Sea.

(It's one of my favorites. Don't believe me? I wrote a book about it!)

Number 1: Early public transportation in San Francisco was animal dependent. Real horse power! Horse car lines, in which the animals pulled little coaches on rails, spider-webbed out from the core of the city. Above is an example on South Van Ness Avenue near 25th Street in 1886. (By the way, the house on the right with the red arrow pointing at it? That's the landmark Frank M. Stone house, still standing at 1348 South Van Ness. Check it out sometime.)

When these horse car lines began being replaced by more efficient electric streetcars in the 1890s, the transit companies faced a dilemma: what to do with the obsolete cars?

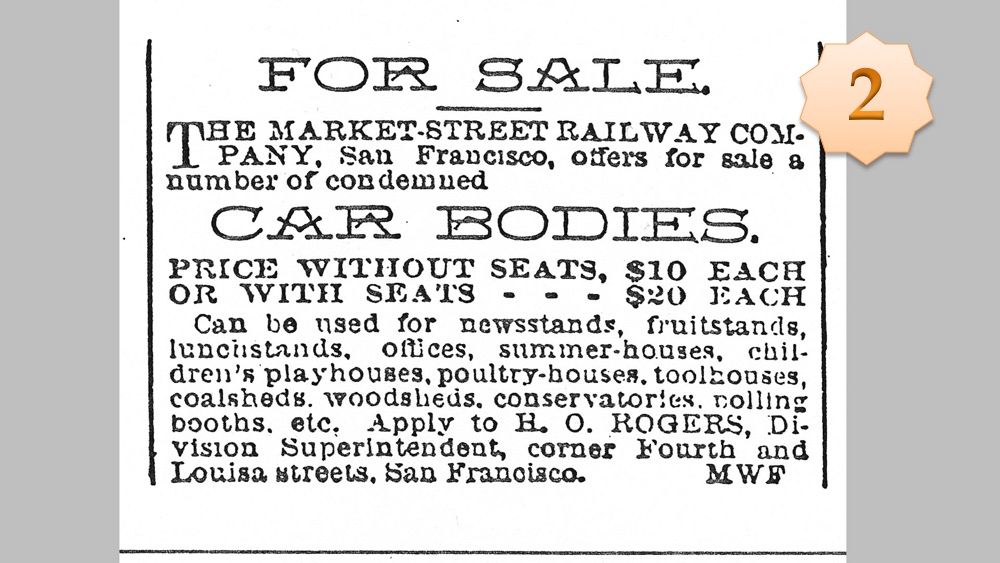

Number 2: Take out an ad in the paper! In 1895, the Market Street Railway offered car bodies with seats for $20 and without for $10, to be used for... well you can read in the ad above some of the ideas. It’s a credit to the company’s imagination that the old horse cars were employed for just about all of those uses.

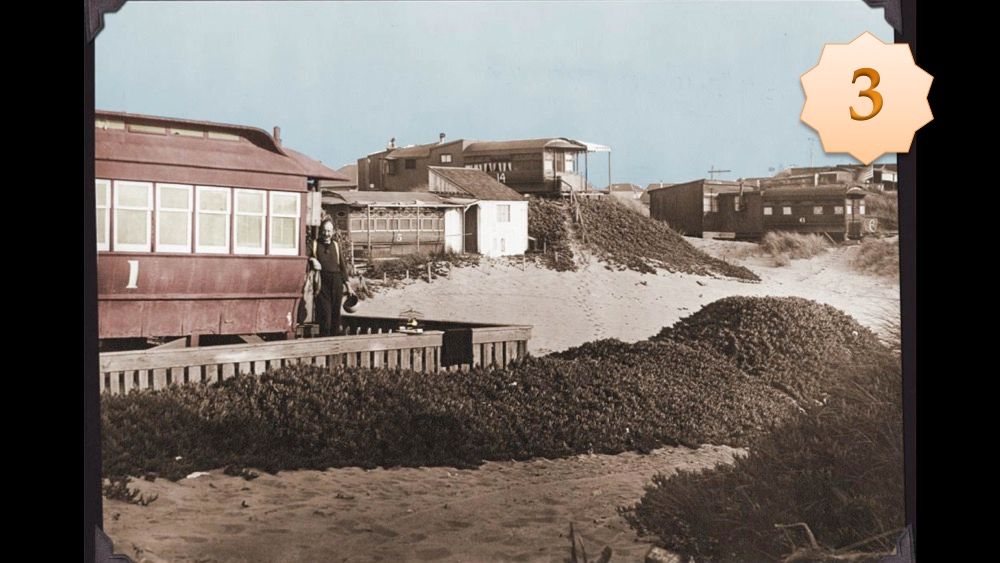

Number 3: Adolph Sutro purchased a handful of cars and offered them for rent on one of his blocks in the cold foggy sand dunes facing Ocean Beach just south of Golden Gate Park. Sutro planned his seaside property to be a new French Riviera, but since he hadn’t invested in any water lines, gas lines, sewage, sidewalks, or indeed any infrastructure whatsoever, the short-term plan was to make some income off the land, even if it was just $5 a month in rent from an old horse car.

The #1 car above was named “La Boheme” by the musicians who used it as a clubhouse and watering hole after their downtown theater shifts. They facetiously called the sand hill behind the car “Mount Diablo.”

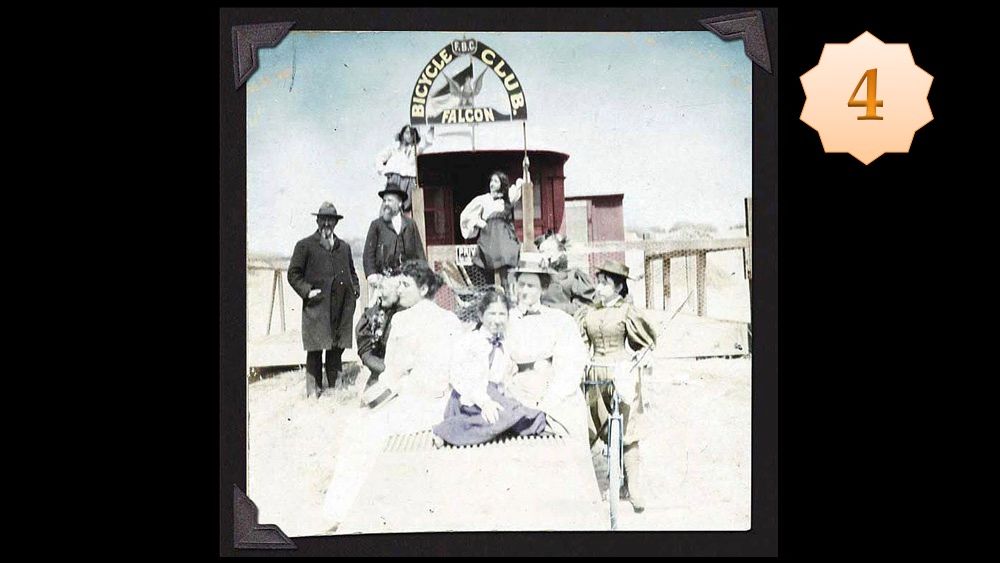

Number 4: A neighboring car was claimed by a club of seven women bicyclists and their admirers. Bicycling was all the rage in the 1890s and after long rides through Golden Gate Park, the “Lady Falcons” used their highly-decorated car for naps and elaborate dinner parties.

Number 5: A block south of Sutro’s property, real estate man Jacob Heyman had tried unsuccessfully to sell in the sand dunes until he decided to go along with Sutro’s strategy. Rather than be restricted to renting, Heyman purchased a couple dozen old horse cars and offered to throw them in as instant housing to anyone who purchased a lot. He built creative rental properties to illustrate possibilities and, most importantly, he tapped the aquifer for groundwater, making full-time living at the beach viable.

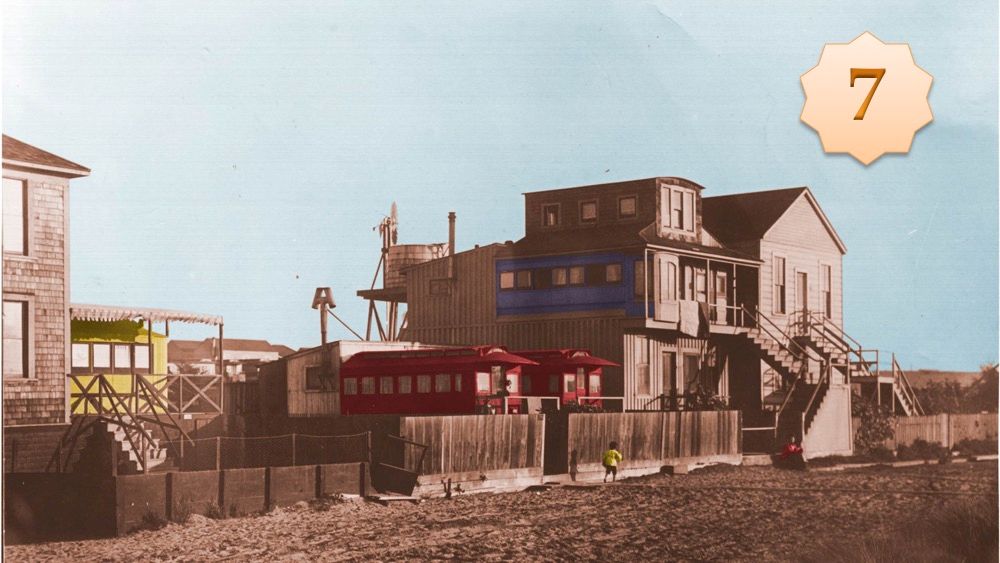

Number 6: Here are Heyman’s cars awaiting potential buyers and some of the rentals going up in the background. By the way, all this colorization of old photos was done by me to give my book a old-postcard vibe. Don’t take it for reality!

Number 7: The creative carpenters responded to Heyman’s temptations and pumped-up water. Carville grew quickly with private homes, bars, eateries, bed-and-breakfast inns, and raucous clubhouses. It became a fashionably shabby, quirky colony of some 200 cars by 1900, drawing bohemians and the wealthy playing bohemian, school teachers on a budget, and rakes looking for a hideaway to carry on quiet affairs.

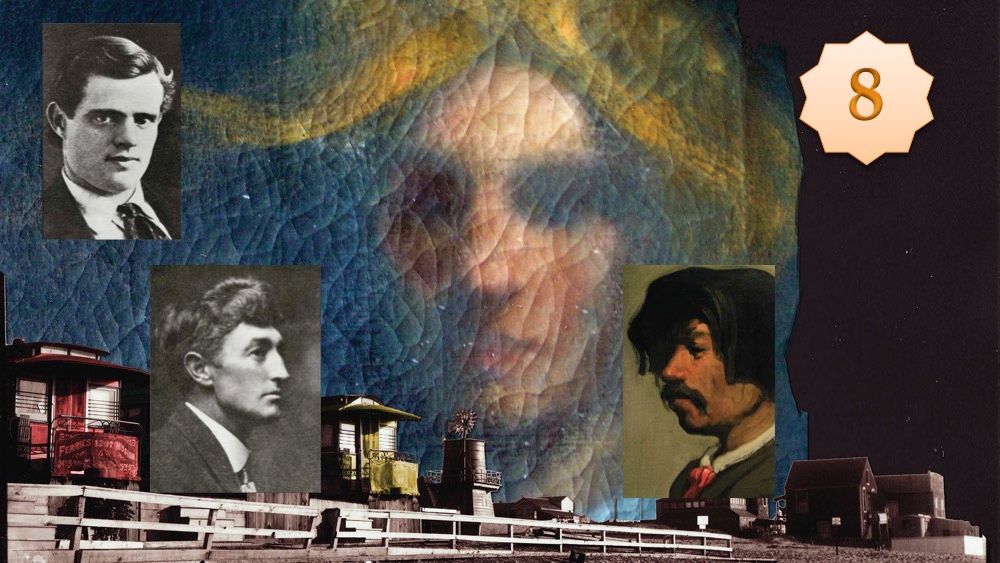

Number 8: Drinking? Affairs? Night-time skinny-dipping in the surf? Sounds like a place artists would be drawn to and they were. Visitors and part-time residents of Carville included the writer Jack London, poet George Sterling, humorist Gelett Burgess, the journalist Maisie Griswold, and the artist Xavier Martinez, who rented a car as a studio. (Griswold is the subject of the background painting above, done by Martinez.)

Number 9: After the 1906 earthquake and fire, an exodus of people from the burned-out core of the city moved west and constructed conventional houses at the beach. Sidewalks and sewage lines replaced the open dunes and a real neighborhood developed as Carville transformed into the Outer Sunset District. Most of the artists bailed for Carmel and other colonies, and by the 1920s, car houses were demolished, relegated to backyard sheds, or hung on as decaying rental properties.

Number 10: Is it all gone? There’s at least one Carville building still standing on the Great Highway, made of three cars artfully combined on a second story. Check out the photo above. That's two cars smooshed together to make one great living room. Perhaps there are more Carville homes hidden away? Let me know if you find one!

These ten images just scratch the surface of the San Francisco Story of Carville-by-the-Sea. Want to read more? Get the digital version of my book, which includes a new afterword and some great bonus photographs and artwork done by friends and fans:

Carville-by-the-Sea: San Francisco's Streetcar Suburb (2022 Digital Version)

Available in EPUB and PDF format for $9.99