Chinatown Demolition

Plague fears led to chopping down parts of San Francisco's Chinatown in 1903.

In March 1903, Tin Lee needed a job and advertised his services in the newspaper: “Chinese first-class French and German cook; good references. 720 Stockton st.”

A month later, he had bigger problems. His home was about to be demolished.

San Francisco’s Board of Health had just won a power struggle with the mayor, Eugene Schmitz, and with new members sworn in, immediately wanted to flex its muscle. Cases of bubonic plague were suspected to have broken out in the city over the winter (although the major newspapers, especially the San Francisco Chronicle, denied it).

The board decided it was time to send ax men to Chinatown.

Chinatown usually played scapegoat for any public health issue in the city. Germ theory was only just being understood and “miasmas,” smells, and even shadows were still blamed for illnesses. Such explanations easily dovetailed with the intractable intolerance the Chinese-American community endured from newspaper editors, sand-lot orators, and the mayor whom Schmitz had just replaced, James D. Phelan.

Racially restricted and crowded in a ten-block section of the city, the Chinese suffered the most from any contagious outbreak in San Francisco and then found themselves blamed for it.

When plague was discovered in the city in 1900, all of Chinatown was put under a general quarantine for fumigation. There were political denials, conspiracy theories, racial scapegoating, and all the other disturbing and frightening aspects of a deadly infectious disease at loose. We, in 2024, are sadly well acquainted.

Board of Health president Dr. J. M. Williamson came out of that experience with some definite ideas of what should happen to prevent further outbreaks, which conveniently coincided with periodic public campaigns to push the Chinese community out of San Francisco:

“Chinatown, as it is at present, cannot be rendered sanitary except by total obliteration. It should be depopulated, its buildings leveled by fire, and its tunnels and cellars laid bare. Its occupants should be colonized in some distant portion of the peninsula […] in this way and no other will there be safety from the invasion and propagation of Oriental diseases.”

(The 1900 plague outbreak seemed to have arrived from Australia, where the Examiner pointed out that 176 of a documented 179 cases there were white people.)

Williamson took a few more eyebrow-raising shots in his 1901 annual report that sadly sounds a lot like some of today’s elected officials: “The day has passed when a progressive city like San Francisco should feel compelled to tolerate in its midst a foreign community perpetuated in filth, for the curiosity of tourists, the cupidity of lawyers and adoration of artists.”

A year later, there were rumors plague had returned. The Board of Health set rat traps in Chinatown in November and December of 1902, and of the 481 rats autopsied, 15 were infected with bubonic plague. (They were on the right track with rats, which can carry the fleas which spread the bacterium.)

The testing was done by doctors at the U.S. Marine Hospital, who pointed out that no one sent them rats to test from other parts of San Francisco. The outbreak passed quickly, at least in Chinatown. Of the 324 rats caught there over the next two months, none had plague.

No matter. The Chronicle, still saying plague was fake news (they almost used that exact phrase), didn’t want to see a crisis, even a fake one, go to waste. The newspaper had been advocating to push the Chinese out of the city for years.

“[I]t is not improbable that the fake reports of plague may silence criticism and obliterate a section which outsiders assume they regard as an attraction and a source of revenue. Let us have a free hand and the growing feeling that Chinatown is a nuisance which will be a perpetual menace to the prosperity of the city will soon suggest a way to get rid of its dubious attractions.”

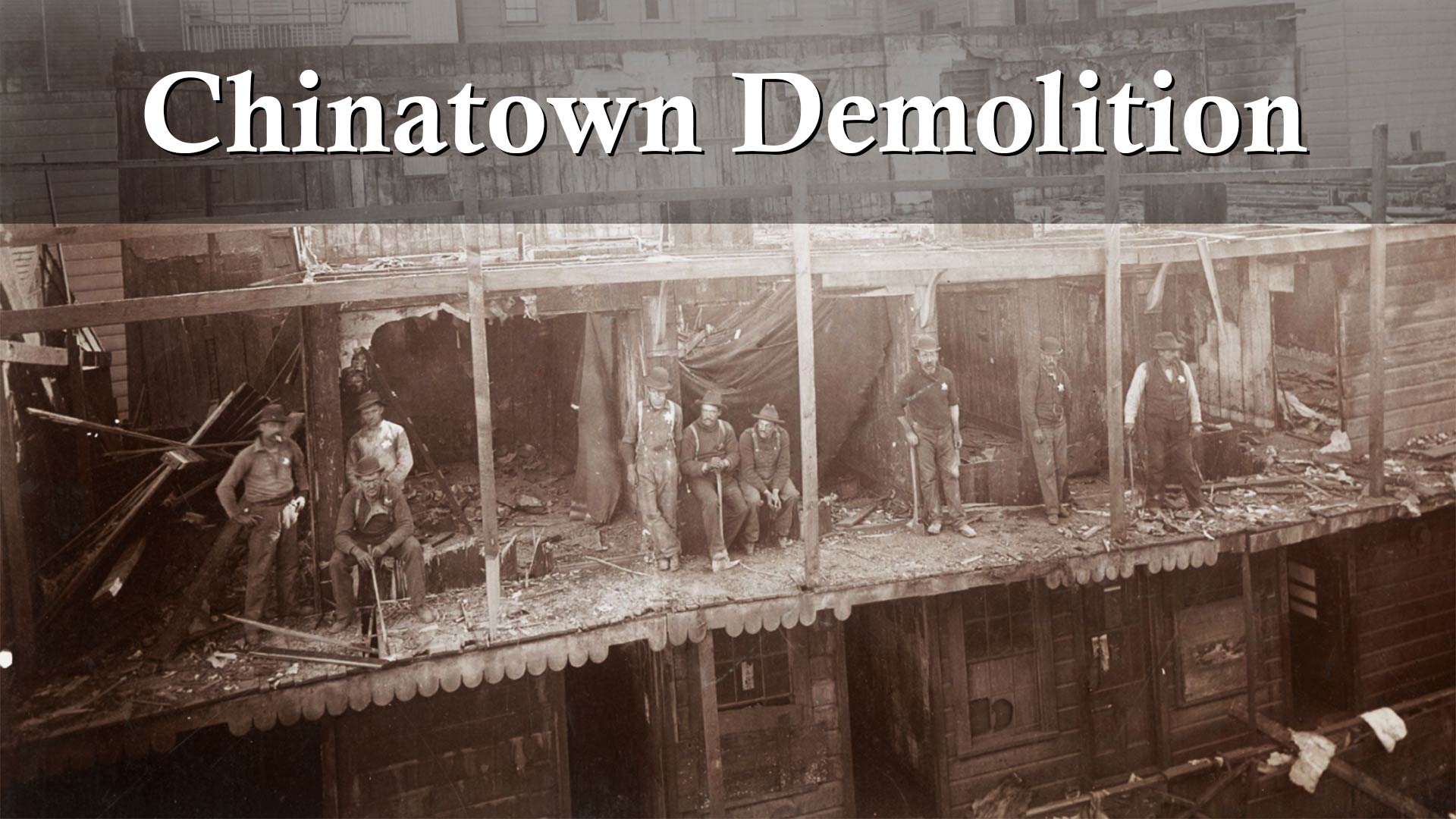

The Board of Health got the state and federal government onboard and sent the Police Department out with axes to start hacking down Chinatown buildings. The progress was documented in an album held and now digitized by the San Francisco History Center at the San Francisco Public Library.

Correlation with plague didn’t seem to be taken into account as much as eliminating spaces which blocked “admission of light and air,” deemed to constitute “a menace to the health of the city.”

Some of the structures cluttering alleys and back lots were pretty bad:

While others looked fairly OK, at least from the front:

These photographs offer some rare and special views of the city, even on the edges. I was particularly attracted to this westerly look up to Nob Hill. Friend Bill Kostura was able to identify the street as the 700 block of Stockton Street. Our cook, Tin Lee, lived in a building just off the right edge of the photo.

Is that a dog or a cat posing on the ledge above the entryway at far left with its owner peeking out the window?

The background building with the cupola housed Leland Stanford’s stables and the house at the top with trees to the right was the old David Porter property, about to be obliterated itself for the construction of the Fairmont Hotel.

Here’s a different view of the Porter house on California and Powell Streets:

The Board of Health couldn’t clear all of Chinatown. The district had on its side some political clout, lawyers, moneyed interests, and public sentiment—tourism was actually a thing even then. Property owners filed injunctions. Deal-making and compromises were made on the down-low and ultimately only alleyway sheds, rambling back additions, and a few of the most derelict buildings were razed.

The order was given to tear down the buildings, balconies, and wooden sheds in the rear of 10, 12, 14 Sullivan Alley (about where Jason Court to today); 708 and 718 Jackson Street, 18-32 Stout’s Alley (today Ross Alley); 831 to 837½ Clay Street; 843 to 875 Clay Street; and buildings adjoining Oneida Place, which apparently included the east side of the 700 block of Stockton Street.

Also on the list? 718-720 Stockton Street, a fairly substantial brick building where the cook Tin Lee lived. The building’s owner was told to “explain to the Board why it should not be torn down,” which sounds suspiciously like an invitation to cut a deal and, in the end, it might have been saved.

Three years later, both the Chronicle and J. M. Williamson got what they wanted when the whole district burned to the ground in the fires following the 1906 earthquake.

With Chinatown’s “buildings leveled by fire, and its tunnels and cellars laid bare,” plague still returned again to the city in 1907.

The outbreak was blamed by the head of the Marine Hospital Service on fleas from an infected ground squirrel. So much for the Oriental disease theory.

Woody Beer and Coffee Fund

Is Woody LaBounty still Woody LaBounty if he doesn’t live on the west side of town? It’s a good question to consider as Nancy and I consider scaling down and moving to some place like Chinatown, Russian Hill, or North Beach. Maybe we should do a poll, or at least talk it over as I buy you a drink using the ducats deposited in the Woody Beverage Fund.

Let me know when you’re free and we can draw up one of those “pro/con” lists on a napkin or even come up with a new identity for me, like maybe “Beatnik Lazar” or “Dewey LaFontaine.”

Sources

Charles McClain, “Of Medicine, Race, and American Law: The Bubonic Plague Outbreak of 1900,” Law & Social Inquiry, Summer 1988, pgs. 447–513.

Joan B. Trauner, “The Chinese as Medical Scapegoats in San Francisco, 1870–1905,” California History, Spring 1978, pgs. 70–87.

“Plague Fake Put Through,” San Francisco Chronicle, May 30, 1900, pg. 9.

“San Francisco Merchants in Mass-Meeting,” San Francisco Examiner, June 2, 1900, pg. 14.

“Widen Streets of Chinatown and Purge Place of its Evils, San Francisco Chronicle, July 1, 1900, pg. 11.

“No Cure for Chinatown,” San Francisco Chronicle, November 11, 1901, pg. 5.

“Vicious Acts of the Old Board of Health,” San Francisco Examiner, March 28, 1902, pg. 14.

San Francisco Chronicle, February 6, 1903, pg. 6, col. 3.

“Anti-Schmitz Faction Wins,” San Francisco Chronicle, February 10, 1903, pg. 14.

“The Rat-Infection Humbug,” San Francisco Chronicle, February 27, 1903, pg. 6.

“Situations Wanted‑Male,” San Francisco Chronicle, March 2, 1903, pg. 8.

“Will Remove Obstructions,” San Francisco Call, March 29, 1903, pg. 37.

“Health Board Strikes Snag,” San Francisco Chronicle, April 1, 1903, pg. 9.

“Making Campaign for Cleanliness,” San Francisco Chronicle, April 8, 1903, pg. 11.