Enter Sandman

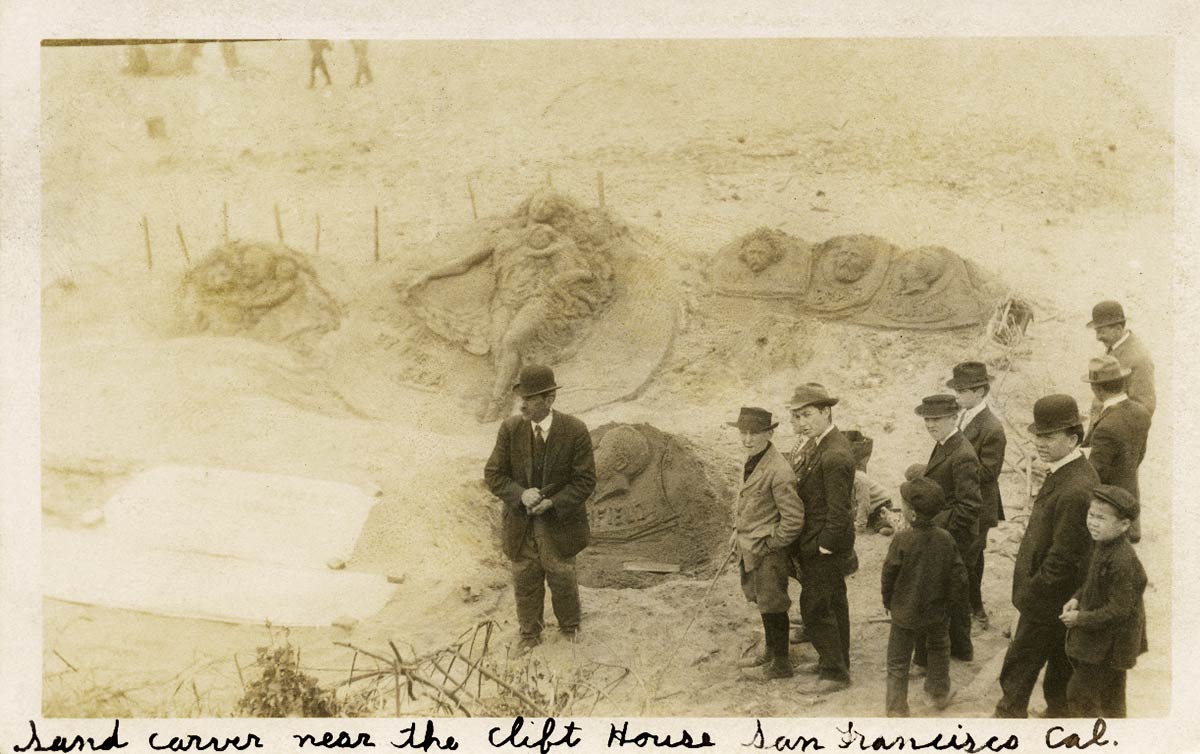

When sand sculptor James J. Taylor came to San Francisco’s Ocean Beach.

This Saturday, October 28, 2023, the 41st annual LEAP Sandcastle Classic returns to Ocean Beach. Benefiting arts programming in education, the event is a showcase of sand sculpture. Architects, designer, structural engineers, and contractors team up with school children and the friendly competition between fundraising teams produces amazing works of surface-tension art.

Long may water molecules be attracted to one another. This year has a Halloween theme, so I expect at least one creepy haunted house and a dog dressed in a witchy costume.

The Sandcastle classic always makes me think of James J. Taylor, who made a living from the 1890s to the 1910s as a renowned sand sculptor. I’ve written about him before, but the best stories should be retold.

Like Bruce Springsteen and Jon Bon Jovi, albeit in a different field of art, Taylor made his fame in Asbury Park, New Jersey, a seaside resort town known for its beach and boardwalk. In the early 20th century, a community of tip-seeking sculptors enthralled visitors with sandy reproductions of floral bouquets, masterpiece paintings, and world landmarks like the Eiffel tower.

Some sources credit Taylor as the originator of sand sculpture at Asbury Park, defraying his expenses while summering at the resort in the mid 1890s. Whether he was the Adam of his community or not, Mr. Taylor was soon recognized as its god.

“A sculptor with an artistic soul and a facile hand,” Taylor repeatedly riffed off one design he entitled “Cast Up by the Sea.” Its centerpiece was a beautiful reclining woman, usually portrayed clutching a child to her breast. Hours were spent getting her impressive dress folds and hair tendrils just right.

Was this an exercise in pathos, a depiction of a shipwreck drowning? Or was the woman some goddess of the sea escaping with her child from a jealous Neptune? Perhaps she was a heroic avatar of motherhood, a modern Madonna, a Star of the Sea for sailors. As with most art, you are on your own.

Taylor almost always flanked his maternal Venus with incongruous friezes of famous men, usually presidents and Civil War generals. Perhaps he discovered this kind of mash-up brought the best tips, which ranged from $20-$30 a day. Or maybe he just liked showing off his range.

For a few years, Taylor (or perhaps the publicity-seeking New Jersey resort owners) put out an annual challenge: a cash prize to any sand modeler who could best the king. Taylor won whenever anyone actually took him on, which wasn't often. “Sand artists are plentiful,” noted one paper, “but evidently they are afraid to compete with Asbury Park’s champion.”

Summer competition for the attention and tips of tourists at Asbury Park increased. The beach crowded with other artists as well as untalented panhandlers scratching anything in the sand. When advertising worked its way into some of the creations, city authorities began regulating the sculpting. In 1907, Taylor attempted to form a union of sand artists to “weed out the undesirable element.”

It may have all been too much for the sand man. He left New Jersey and took his talents on the road. In 1908, he found a home in Long Beach, California.

In California, Taylor followed a liberated, if precarious, livelihood, dependent on the climate and an audience. “Taylor does not exert himself unless there is a goodly crowd on the strand, for he has followed the work so long that he has grown worldly-wise.”

In addition to “Cast Up,” he frequently offered Long Beach visitors mermaids, menageries of lions and racehorses, and allegorical sculptures of Southern California as a goddess with a cornucopia.

Taylor made occasional road trips up the coast to other beaches, including as far as Seaside, Oregon. In 1909, “Cast Up by the Sea” finally appeared on San Francisco’s Ocean Beach. The local newspapers were impressed with the mother and babe and the portraits of prominent men Taylor chose for the side friezes: poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, General Grant, President Taft...

“The boys and girls who delight in making mud pies or sand pies on the beach were speechless with astonishment,” reported the San Francisco Chronicle, “and asked the man to show them how to make such nice things.”

James J. Taylor spent the last decade of his life in a small Long Beach shack, sculpting to the end. According to one newspaper, he cared “only that his talent should bring enough for the most meagre subsistence.”

The sand ran out of his hourglass on August 4, 1918, when pneumonia got him after a month-long illness. He was in his late 50s, and an obituary noted that for all his fame as “the sand man,” few knew “little of the life or affairs of the man.”

Woody Beer and Coffee Fund

I don’t think Patrick S. (F.O.W.) understood the rules of the Woody Beverage Fund. He bought my beer (and dinner!) at Tommy’s Mexican restaurant. I got you next time, Patrick. How about you, dedicated reader? Are you ready to have me purchase you a drink? Let me know when you’re free.

The beverage bank is always open for donations. Force me to be sociable!

Sources

“Taylor Re-Engaged,” Asbury Park Journal, June 4, 1901, pg. 1.

“To Model Sand in Eagle Hall,” Asbury Park Journal, May 8, 1903, pg. 3.

“Sand Sculpture,” Los Angeles Herald Sunday Magazine, December 6, 1908, pg. 6.

“Mayor Stoy as ‘Art Critic,’ Los Angeles Evening Post-Record, April 19, 1909, pg. 4.

“Beach Artists Have a Defender,” Atlantic City Daily Press, July 21, 1909, pg. 1.

“Museum Receives Valuable Curios,” San Francisco Chronicle, December 6, 1909, pg. 14.

“Sands of Life Ebb for J. J. Taylor,” Long Beach Press, August 5, 1918, pg. 12.