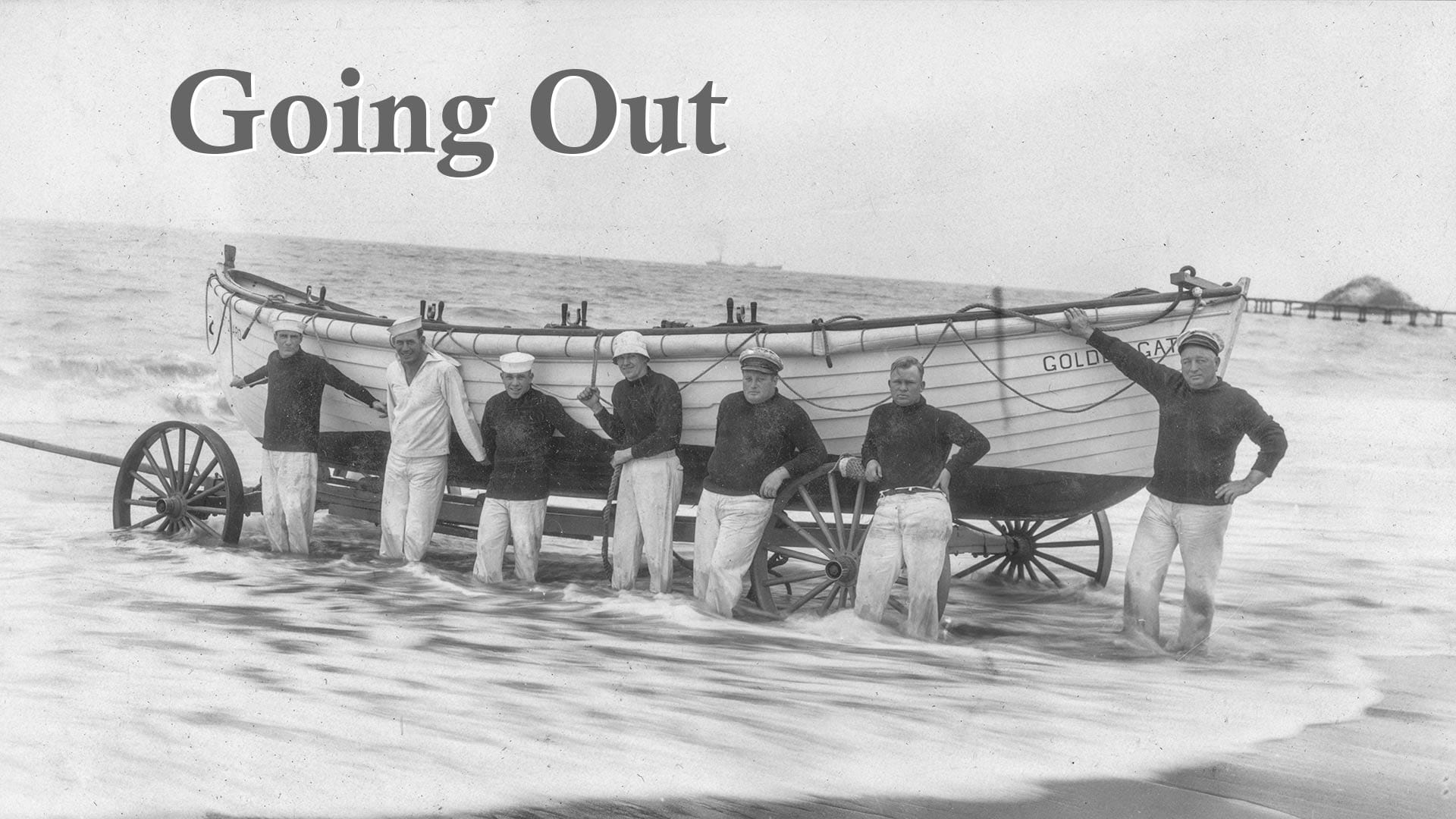

Going Out

Life Saving at San Francisco's Ocean Beach

When I was a kid there were large signs on the Ocean Beach seawall warning of dangerous undertow.

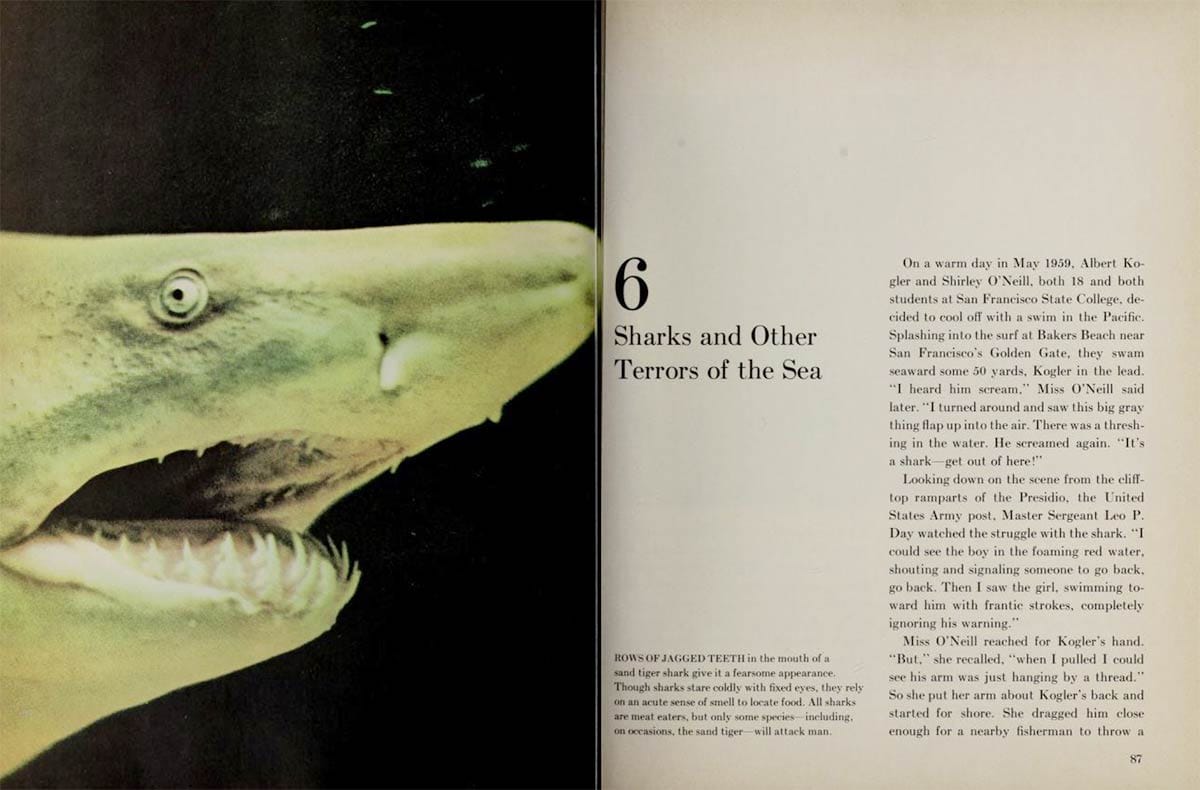

The famous story of the 1959 Great White shark attack at Bakers Beach had its own scary chapter-opening in one of the Time-Life nature books back at our house.

Jaws came out when I was 9, showing at my neighborhood theater, the Coliseum.

So, between the signs and my new paranoia about sharks and poisonous stonefish (thanks Time-Life Books), I was dissuaded me from getting my toes wet at Ocean Beach.

We didn’t even have the lifeguards I’d see in television shows, the ones sitting in their mini-towers telling the detective-of-the-week that they didn’t know anything but, wait a minute, come to think of it, there was something strange that day…

From 1877 to 1951, Ocean Beach did have an official life-saving station, although the men who worked it were not the kind of lifeguards you remember from Baywatch episodes. The primary job of the “surfmen” at the Golden Gate Park station was to rescue victims of foundering and wrecked ships and steamers.

The United States Life-Saving Service (USLSS) was created by congress in 1871. It was the country’s first official and professional agency to meet maritime emergencies. In 1914, it was rechristened and reorganized as the U.S. Coast Guard.

Ocean Beach was the scene of major and many shipwrecks. Historians James Delgado and Stephen Haller identified the seven-mile stretch between Point Lobos and Mussel Rock as one of the highest concentrations of maritime accidents in the Bay Area with twenty-four vessels and sixty-six lives lost between 1850 and 1936.

The beach was a natural spot for a USLSS station and the first was constructed on the northwest corner of Golden Gate Park at Fulton Street in 1877. Later stations were installed down the beach near Lake Merced, at Fort Point, and on what is today Crissy Field.

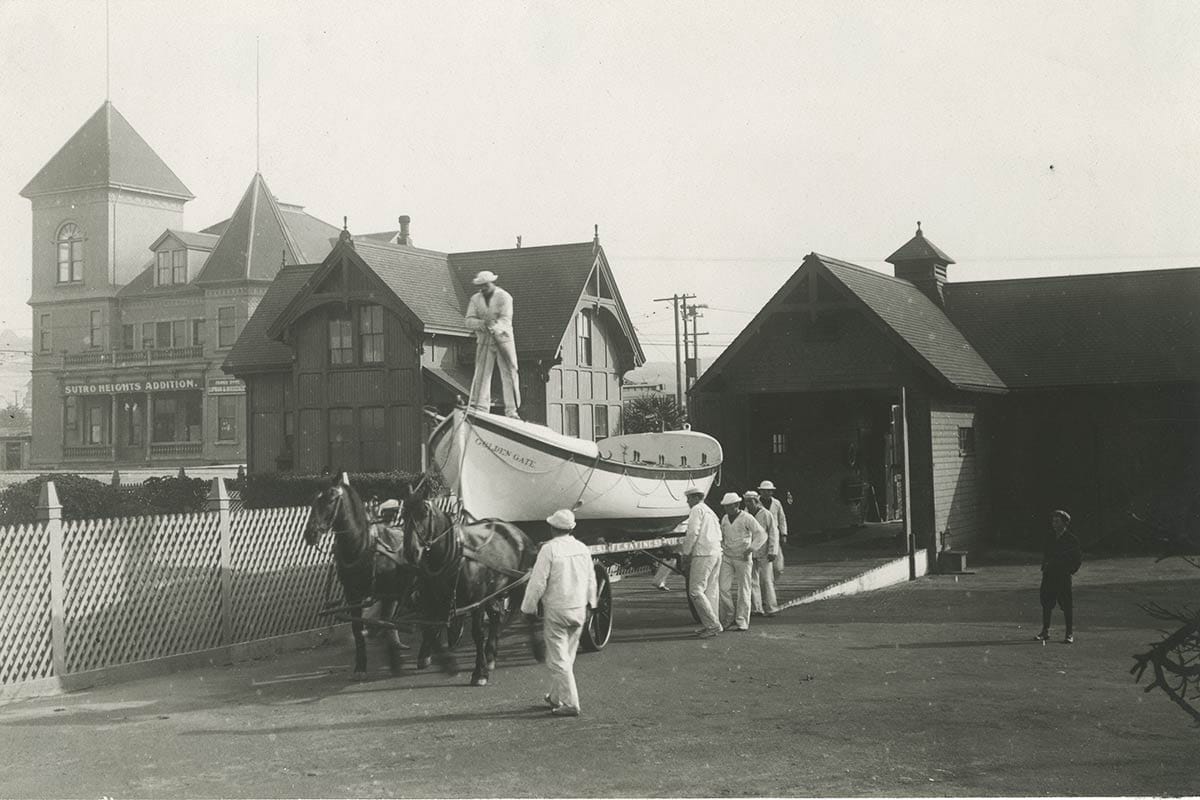

A serious governmental mission of dormitories and equipment sheds could still exude charm. Check out the ski-lodge architecture:

By the late 1890s there were 13 stations up and down the United States’ west coast. Each was manned by a crew of eight surfmen with a captain, the “keeper,” in charge.

The boathouse held two craft, a smaller life boat that could be dispatched quickly for incidents in close proximity to the beach and a big 30-foot-long surfboat able to handle rougher seas and hold up to 50 people.

“This boat can neither sink, nor fill, nor be stoved in, nor capsize, nor turn-turtle, nor ship-a-sea, nor do any of the evil tricks common to boats in a gale,” claimed a reporter. “Once get her out in the open sea and there is practically nothing that can hurt her.”

Getting her out in the water past the surf was the trick and challenge of the crew at Ocean Beach. Breakers and tide could conspire to make launching the big boat from the beach impossible. In such conditions the lifesavers resorted to their “beach apparatus.”

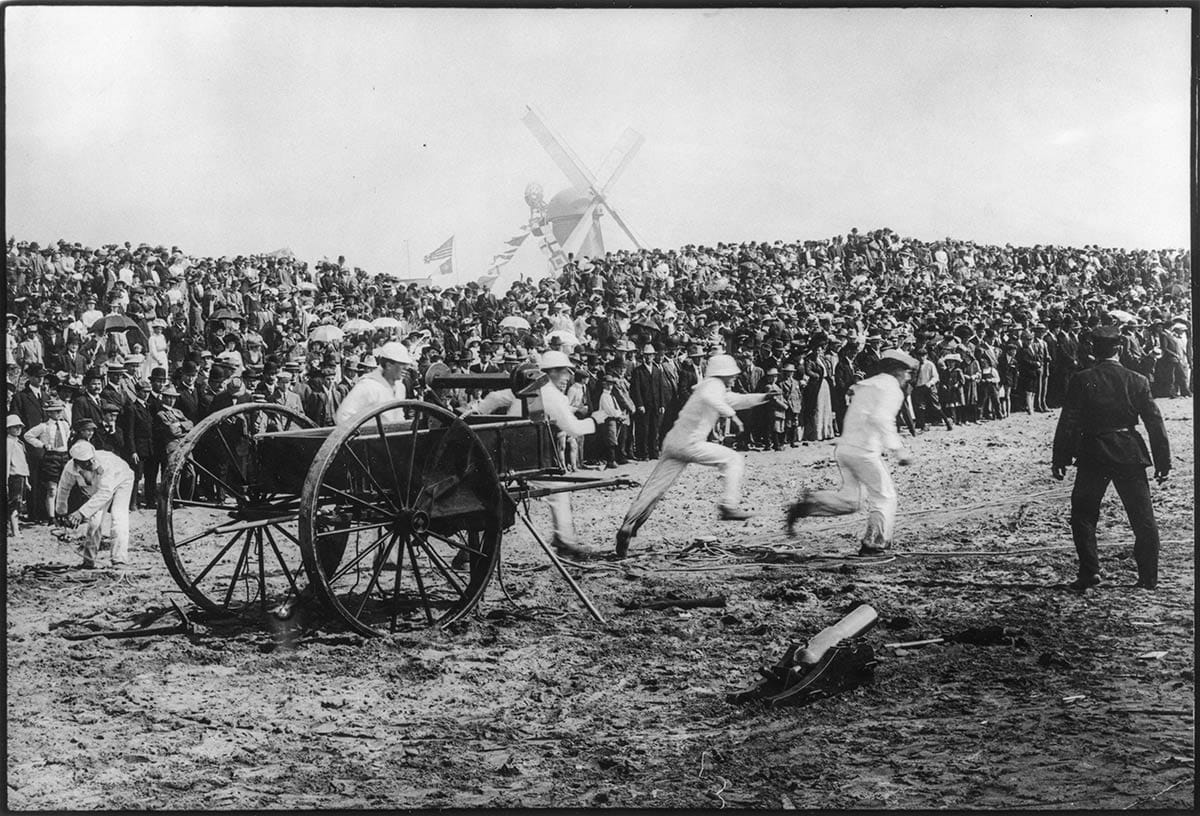

A small cannon on a cart could shoot a line over a foundering ship within 300-500 yards of the shore. With a cable fastened to the ship, passengers could be ferried to shore using a contraption called a breeches-buoy: hanging canvas shorts a shipwreck victim could sit inside akin to a modern zip line.

Patrols walked the beach with flags, doubled up on foggy days, and at night carried torches looking for ships flying any distress signal. Observation towers were set up in places, including above Fort Point about where the Golden Gate Bridge toll plaza stands today. The staff also guarded beached wrecks from looters from time to time.

One good story: when the Bessie Everding came aground on Ocean Beach on the foggy evening of September 9, 1888, the crew abandoned ship and rowed their boats to safety. A patrolling surfman from the Golden Gate station, walking the beach and unaware of the incident, heard a strange howling to seaward.

Seeing the schooner rolling in the breakers, the patrolman rustled up the lifesaving squad, which rowed out to the wreck to find the craft crew-less in spooky Mary Celeste fashion.

The ghostly howling? The ship’s cat had been left behind.

Cat was saved. The crew returned to their wrecked ship the next day, salvaged half the cargo and useful fittings, and abandoned the Bessie Everding to break up in the rollers about where today’s Lawton Street lines up with the beach.

The men of the lifesaving station trained frequently, running their boats out into the surf, shooting their cannon down the beach, practicing resuscitation and flag-signaling. The drills drew large crowds on sunny days and the brave surfmen were idolized by many, much as fire fighters and other rescue personnel are treated today.

The “coasties” responded to dozens of wrecks and stranded craft in their 70 years of service at the beach. Their unofficial motto was “You have to go out. You don’t have to come back.” Cheerful bunch, the coasties…

Can you see Pamela Anderson or David Hasselhoff doing this work?

The larger dormitory building became surplus to the Coast Guard in the 1923. One of the life-savers, Carvel Torlakson, bought it for $75 and moved it to near the corner of 47th Avenue and Cabrillo Street as his family residence. It’s still there, perhaps the oldest surviving structure in the Richmond District.

The days of horses pulling boats to the surf, signal flags, and men at oars all gave way to motorized launches, radios, and helicopter rescues, but the Golden Gate Park station hung on as a Coast Guard operation until late 1951.

The buildings were removed some years later and today there isn’t any sign of the complex where it once was in the park.

Much of the Fort Point Lifesaving Station, which remained in service at Crissy Field until 1989, is still in place if you’d like to visit. And it’s hard to miss the Torlakson house on 47th Avenue, purplest building in town, which has a nice plaque.

Thanks to my friend, John Martini, always a great source of information on… um, everything?

Woody Beer and Coffee Fund

Thanks to Linda G. (F.O.W.), Jim B., and the legendary Mr. Lucky for chipping in to the Woody Beer and Coffee Fund. Thanks to them, I can buy you a beverage and you can tell me that story of when you met that semi-famous person at that great place we both remember which closed long ago. What a crazy and great time, right?

Sources

Leonard Engel, The Sea (New York: Time-Life Books, 1970).

James P. Delgado and Stephen A. Haller, Shipwrecks at the Golden Gate (Lexikos, 1989)

“Life-Line and Surf-Boat,” The Wave, September 18, 1897, pg. 8.