Gold Rush Prefab

"Portable houses" were one solution to San Francisco's 1849 housing crisis.

It is a common truism that those who made money during California’s Gold Rush were not the gold seekers but the men who mined the miners: gambling houses, laundresses, merchants, and provisioners who sold $1 eggs and $100 boots to the Argonauts arriving from around the world.

My great-great-great-grandfather tried to have it both ways.

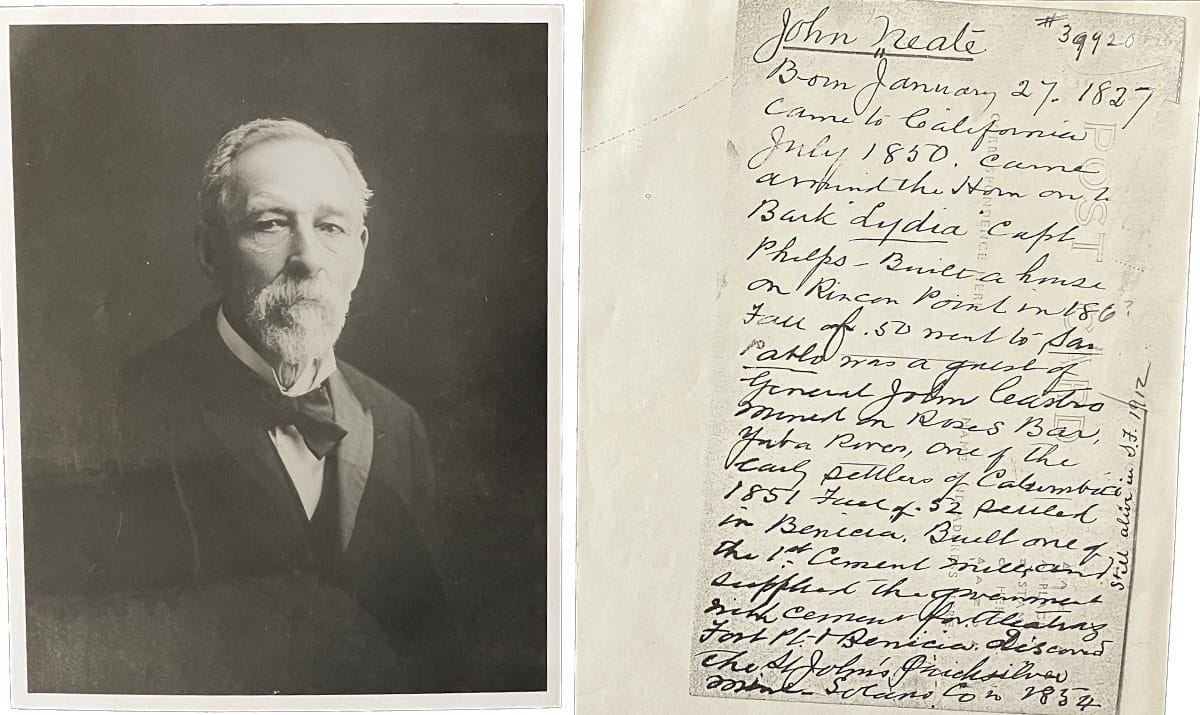

John Neate seemed to have received some technical training in Bristol, England, knew minerals, and something about mining engineering. He did his own gold prospecting at Rose’s Bar on the Yuba River shortly after arriving in California. A couple of years later, he discovered veins of cinnabar in the hills above Vallejo and established a quicksilver mine there.

But on June 9, 1850, when the 23-year-old entered San Francisco Bay at the end of a six-month sea voyage from Liverpool, he arrived with consigned merchandise to make some quick money.

Among the goodies was a sewing machine he later claimed was the first to arrive in California. He sold it in Benicia for $350, which would equal about $14,000 in 2024.

Not bad, and the profit may have given John Neate high hopes for the other items he had lugged around the world in the hold of the barque Lydia: prefabricated iron houses.

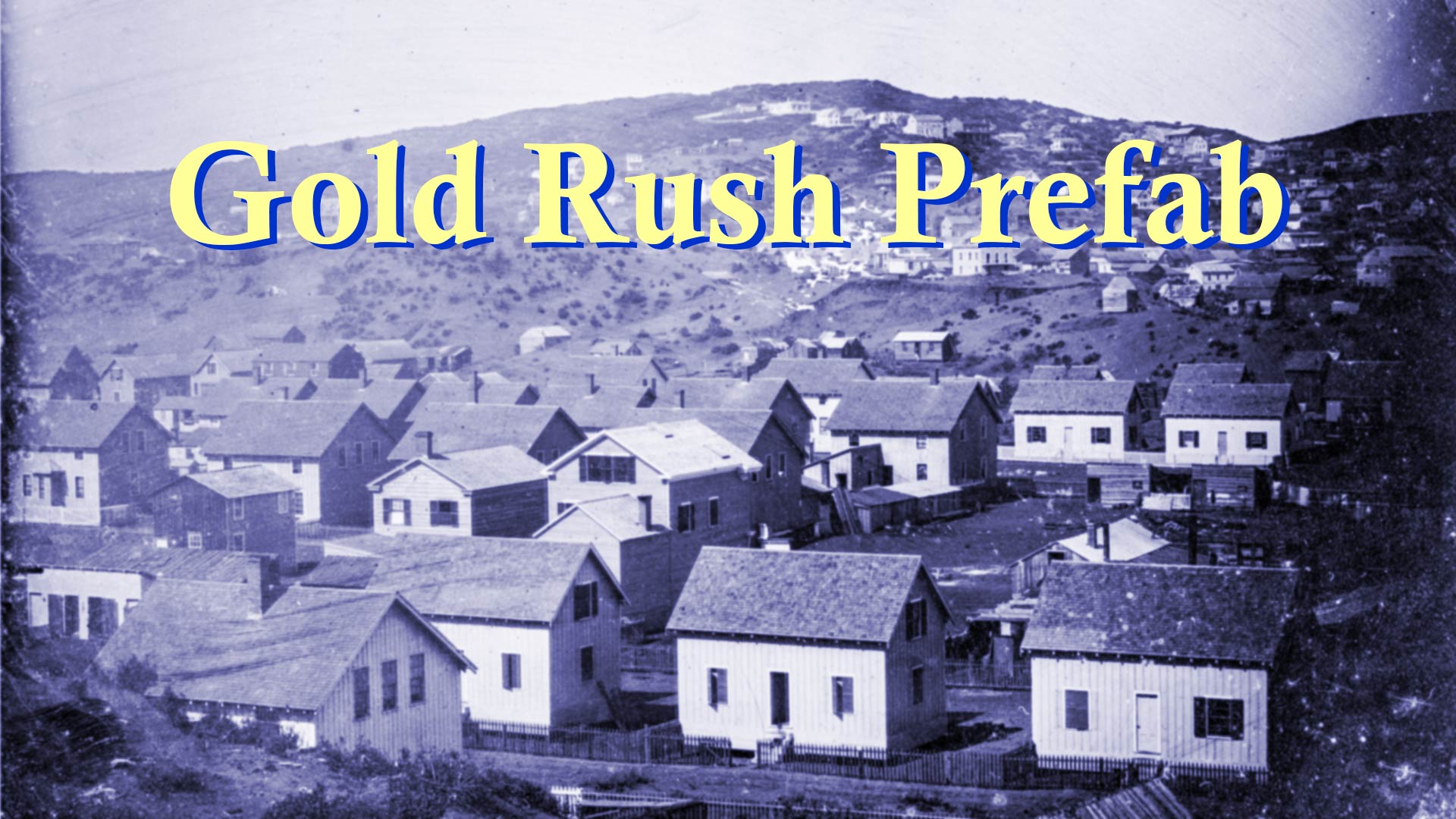

Prefab City

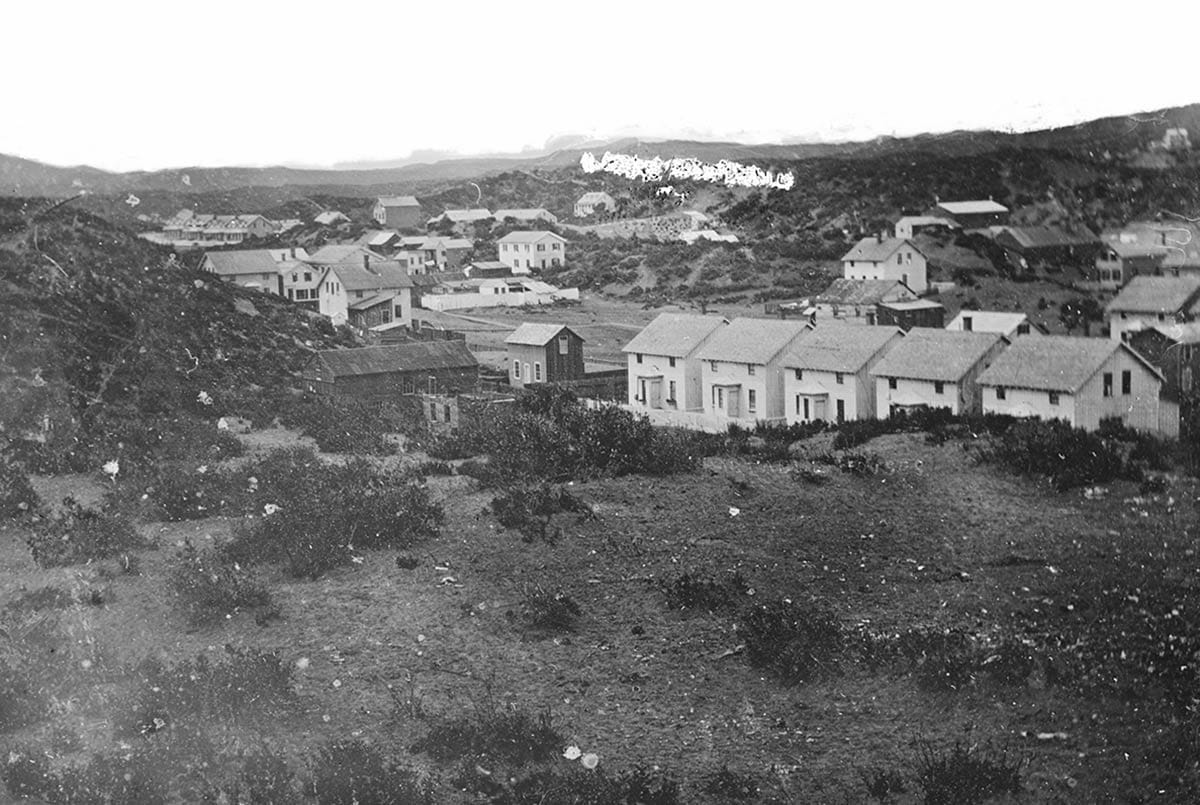

We’re told in 2024 that San Francisco is in a “housing crisis.” Such a statement has been made almost every decade of the city’s existence and even before the city was officially a city. But the phrase had real meaning in 1849 when a world of men all descended on the tip of our peninsula trying to get to the gold fields.

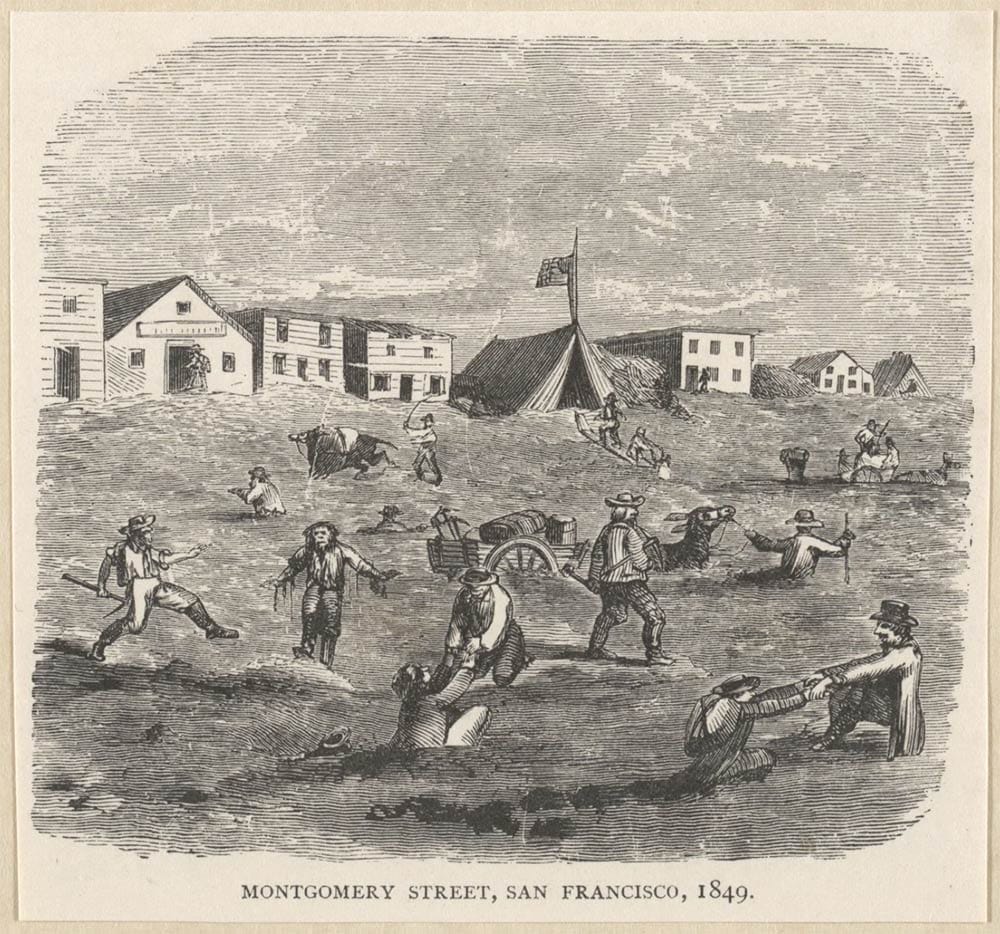

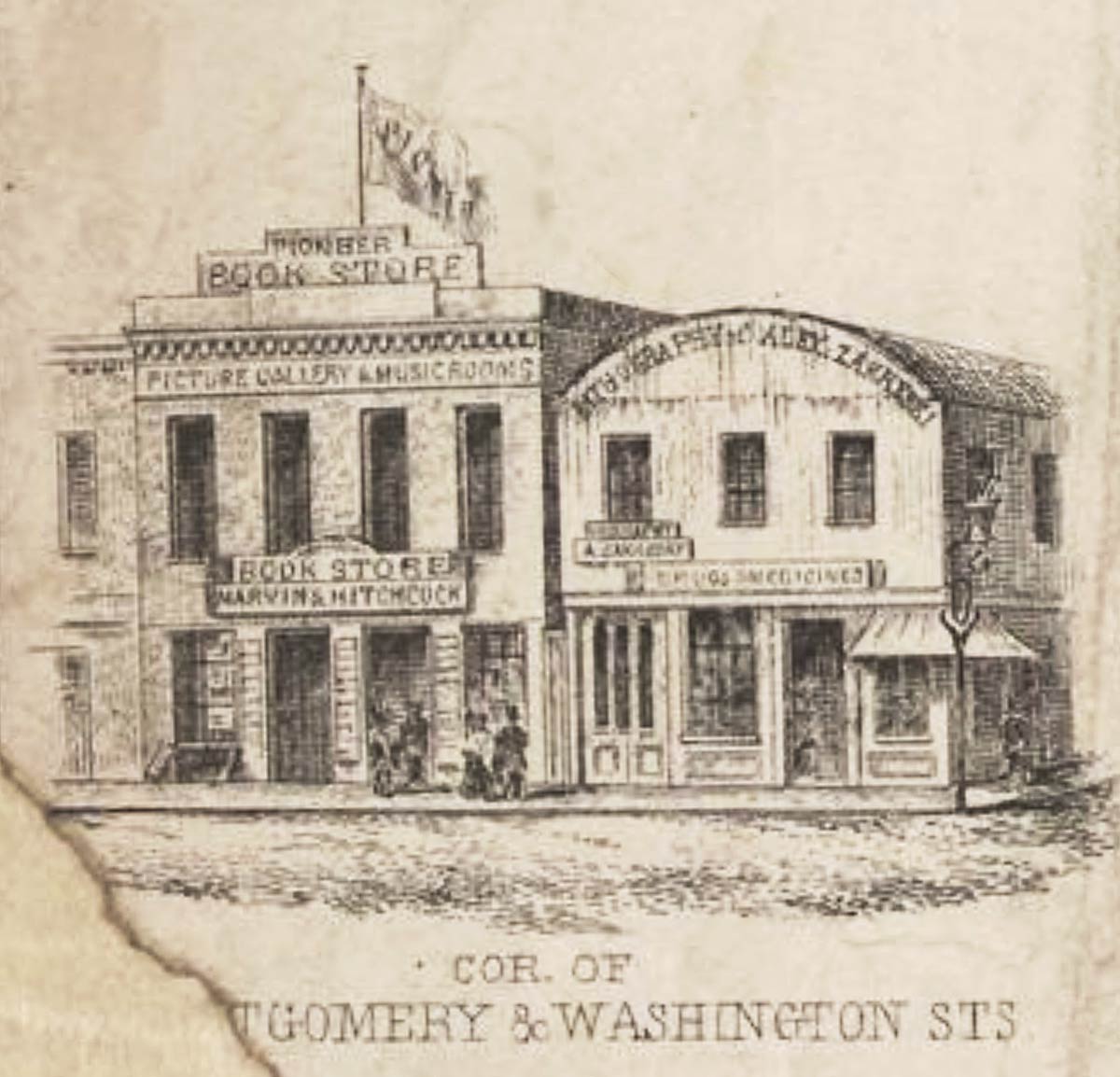

In boomtown Yerba Buena, a village soon formally christened San Francisco, men slept in the rough or in tents in mud and sand. Lucky ones rented cots or benches in shacks or rented stacked flea-infested bunks in hastily erected lodging houses.

“At some lodging-houses and hotels, every superficial inch—on floor, tables, benches, shelves, and beds, was covered with a portion of weary humanity." — The Annals of San Francisco, 1855.

Hotels (using the term loosely) commanded leases of $12,000 to $15,000 a year from property owners and the cost was easily recouped at the expense of tired men seeking a bed or even a stretch of open floor space to recline.

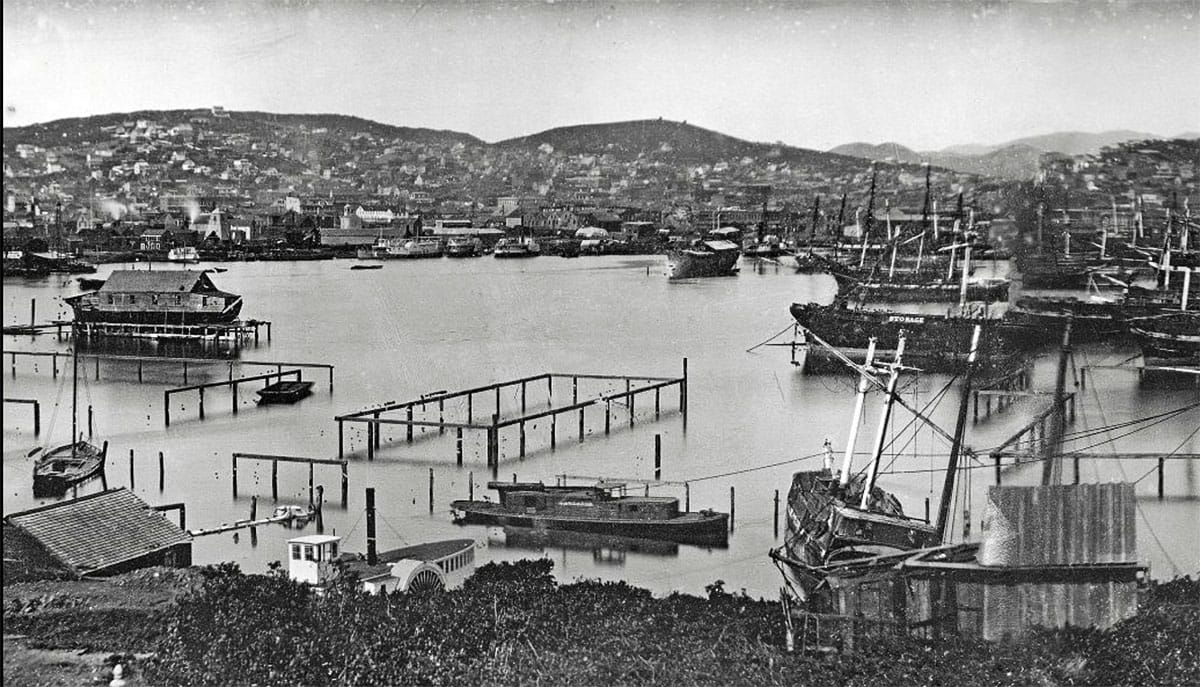

You might find a deal sleeping on an abandoned ship in Yerba Buena Cove, but your daily commute being rowed to shore could cost you $2. (Yes, that was an 1849 side hustle.)

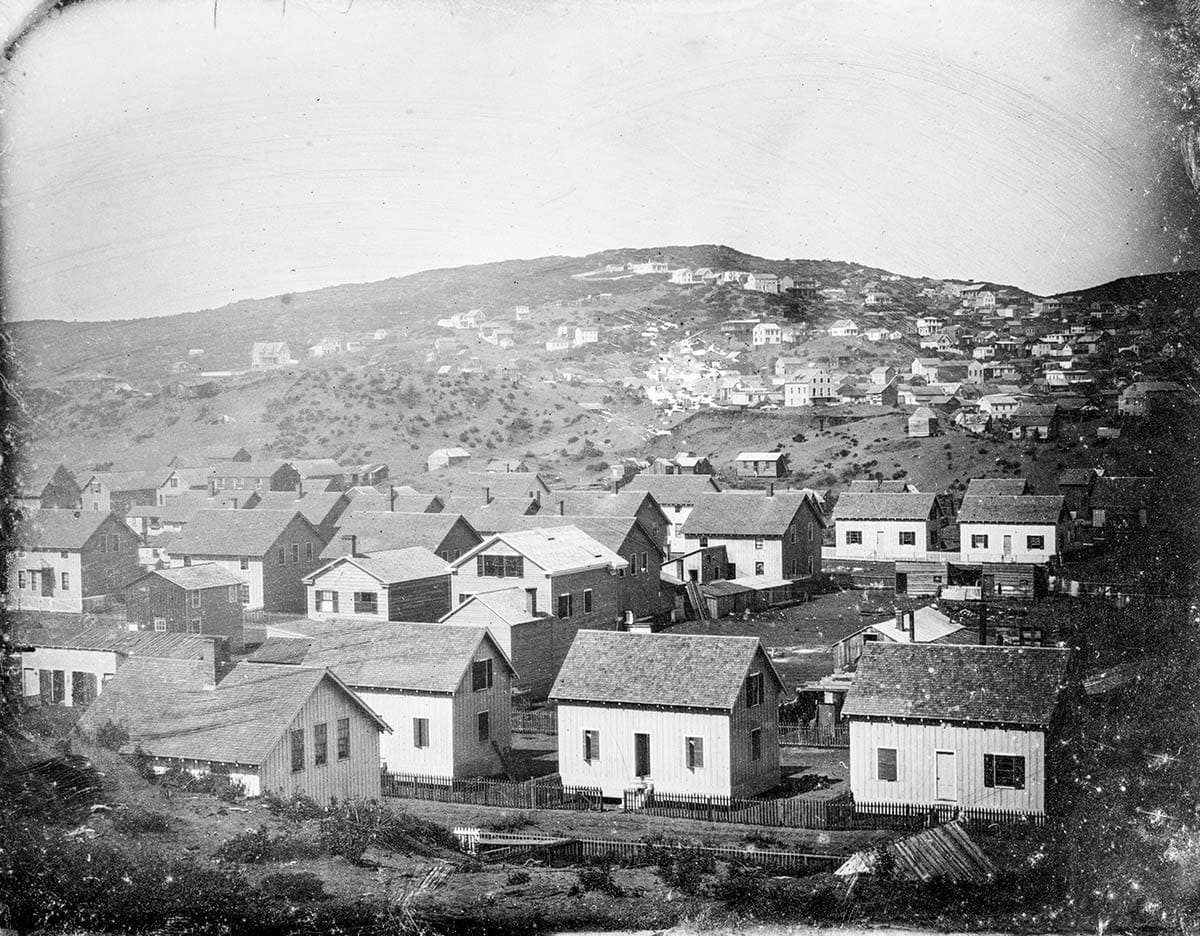

Makers of pre-fabricated housing around the world saw a market for their wares in California. Thousands of partly constructed wood framed houses—not too different from the modular homes and kit cabins of today—were shipped out with construction plans from Europe, New York, Massachusetts, and Maine.

Some of these “portable houses” were tiny and some huge. Some had quaint front porches and others cutesy filigree to nail onto roof ridges and eaves.

Innumerable cottages, multi-story hotel buildings, and even prefab bowling alleys left ports in England, France, Germany, Boston, Baltimore, and Philadelphia to sail around Cape Horn to San Francisco.

Houses came from across the Pacific as well, from New Zealand and Australia and China. Some were sent complete with carpenters to help with the assembly.

I would have sprung for the carpenter upgrade.

Manufacturers promised these things could be erected easily, but we aren’t talking about an IKEA bookcase. A prefab cottage from Hamburg, Germany arrived in San Francisco in 42 large crates, Allen wrench and Swedish-captioned cartoon instructions not included.

Houses of Metal

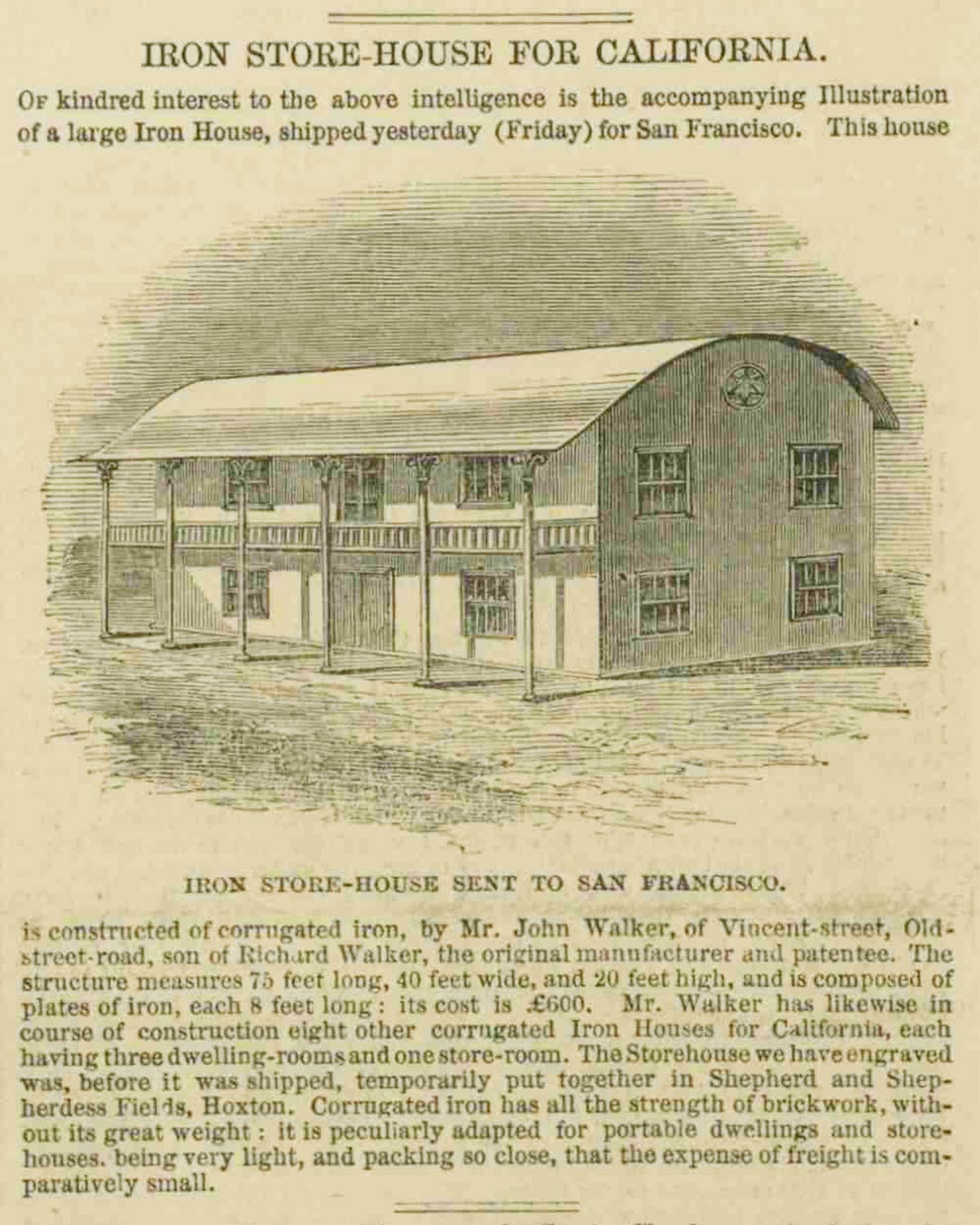

In the prefab world in 1849, iron houses were a relatively recent invention. The chance for gold rush profits accelerated their development, as just about every foundry, blacksmith, and roofer decided to get into the housing business.

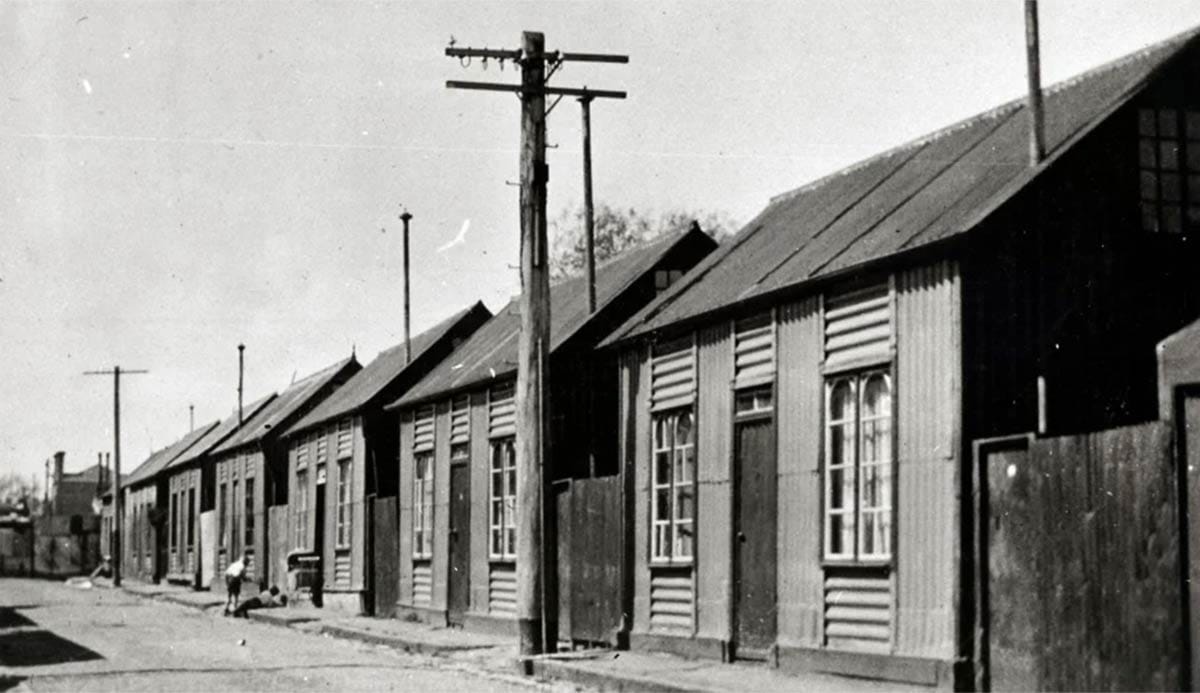

On paper, these erector-set homes seemed perfect for California. A typical model could ship in just two boxes. The roof and walls slid together with grooved posts to create tidy 15-by-20-foot domiciles.

I don’t know of any still standing in California (maybe you do?), but there are surviving examples in Australia to give you an idea of what they looked like.

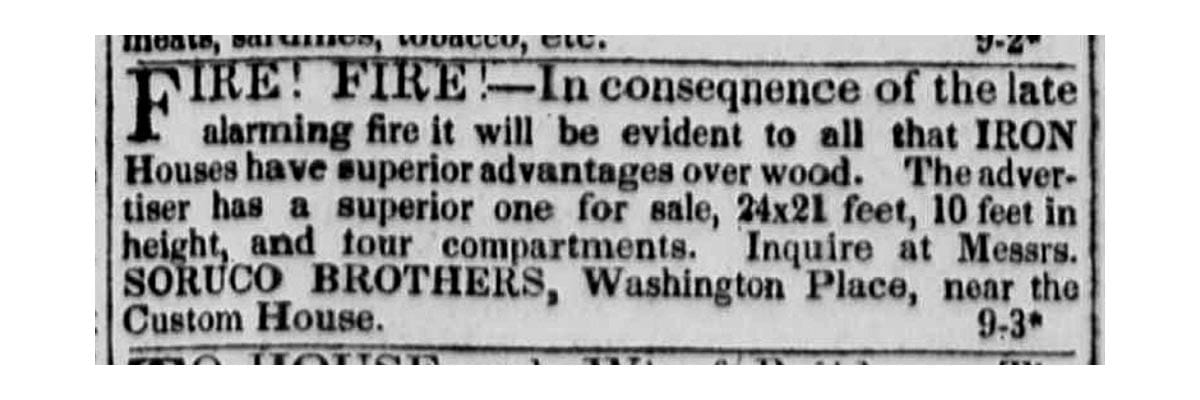

Iron models were cheaper than wood frame houses and much easier to disassemble and re-erect in a new location, which seems like a nice back-up plan for a buyer following gold strikes. Plus, iron houses were marketed as “fire proof.”

The last point was not inconsiderable. San Francisco had five major fires and a bunch of little ones in its first two years of existence.

What could beat a cheap, portable, and apparently indestructible iron house you could mail in a box? If you didn’t want a prefab for yourself, you might still be tempted to get into the business of selling them.

Investment in a $150 framed house in Boston could get you $1,400 the minute you stepped off the boat in San Francisco. In perhaps an extreme example, one iron house purchased for $345 in New York was sold for $5,000 in California.

That was 1849.

By early 1850, while my ancestor’s ship was still working its way up the coast of South America, the market had become glutted with prefabs. Lumber mills had also started to get going on the coast, depressing the cost of building materials.

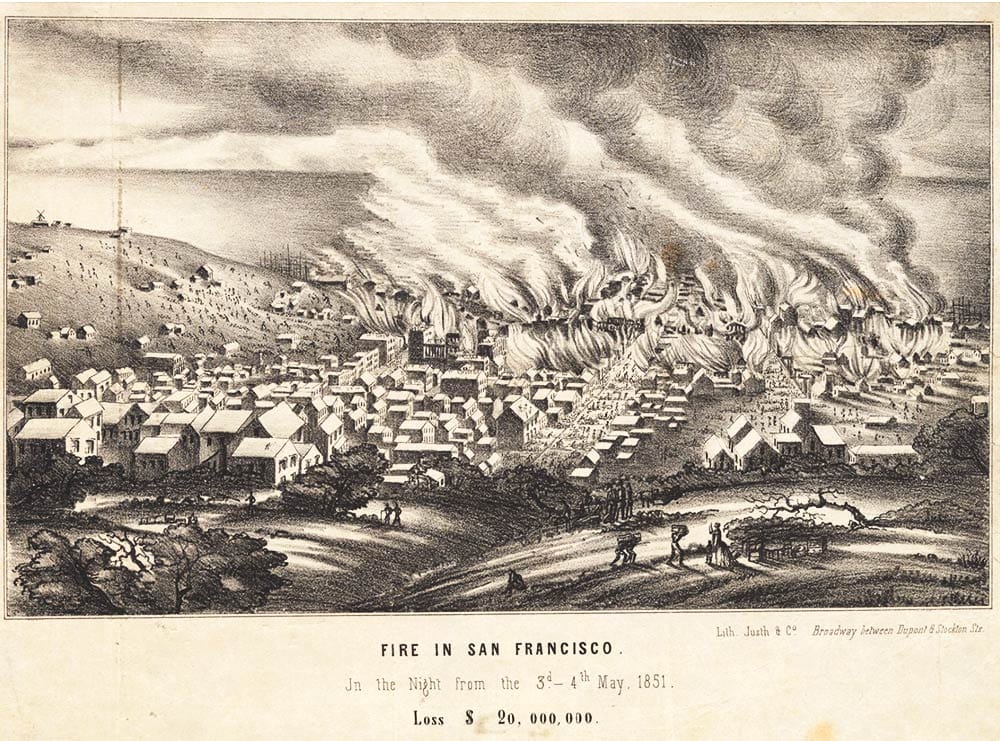

And the iron house proved to have some drawbacks, such as getting uncomfortably hot, even in foggy San Francisco. Then the fire-proof claims took a big hit during the big San Francisco conflagration on May 3–4, 1851.

Men who thought they were safe inside their fireproof buildings soon found that the doors swelled shut from the heat, trapping them in a noxious inferno. And while the structures didn’t burn, they certainly did melt. Yikes.

When all had cooled, to cut up and haul off the warped debris of an iron house cost more than building a replacement wood frame building.

Put me in one of those time-travel movies where I only get to send one sentence back to my ancestor and it’d be: “Stick with the sewing machines.”

Woody Beer and Coffee Fund

The truth is out: my weekly history email is just a sneaky way to entice people to meet me for a beverage, because why live in a beautiful city if you are just going to stay inside watching old episodes of “Northern Exposure?” (Especially when you hit that terrible jumped-the-shark last season.)

Chip in for the cause and let me know when you might be free!

Sources

Pioneer Card, John Neate, California State Library, Sacramento, California, 1913. (Information from John himself, who died in 1919 at 92 years old.)

Frank Soulé, John H. Gihon, and James Nisbet, The Annals of San Francisco (New York, 1855), pgs. 247–248.

T. A. Barry and B. A. Patten, Men and Memories of San Francisco, in the Spring of ‘50 (San Francisco: A. L. Bancroft & Co, 1873), pg. 73.

Charles E. Peterson, “Prefabs in the California Gold Rush, 1849,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, December 1965, pgs. 318–324.