Gold Star Corners

San Francisco's 1943 plan to remember its war dead.

“Kenneth Lee Campbell, we salute you. San Francisco will never forget.” — Acting Mayor of San Francisco, Jesse C. Colman, on May 30, 1943.

I’m working a lot of weekends these days and planned to do the same on Monday’s Memorial Day holiday.

Then I changed my mind.

Like a lot of people, I consider war the ultimate failure. But I know it’s easy to hold convictions from a comfortable remove of time, distance, and connection. My cousins aren’t starving, my brothers aren’t fighting, my children aren’t dying. My abhorrence for war cannot desensitize me to those who suffer or have suffered.

To reject the societal amnesia that allows “never again” to become “here we go again,” we periodically need to reopen old wounds. We need to remember.

So, Monday I took a walk across the city to honor four San Franciscans killed in World War II, four men the city vowed to not forget.

Gold Star Corners

Memorial Day needed to be properly commemorated in 1943 San Francisco. The war was at its height. More than 405,000 Americans would die in the conflict, with 17,000 casualties coming from California and by the end of the war, hundreds of San Franciscans.

In early May 1943, prodded by a newspaper editorial, the Board of Supervisors passed a unanimous resolution that the city was “determined that her veneration of our gallant defenders shall not be ephemeral, but shall be a constant and visible reminder of the exhalation in which they are held.”

The “constant and visible” venerations the city came up with, helped by the Call-Bulletin, took the form of an “honor scroll” listing the city’s World War II dead, and “gold star corners.”

Born out of a World War I commemoration movement, gold stars represented individuals who died in service. We still have this tradition and Gold Star family organizations today.

The city sought to officially expand upon this idea by affixing above street signs and on light standards the names of San Franciscans “who made the supreme sacrifice.”

The placards would be posted near the former homes of the deceased and surmounted by a gold star. The intent was to “honor the memory of the hero forever.”

For Memorial Day in 1943, four men were chosen to start the gold star corner program, one each from the Army, Navy, Marine Corps, and Merchant Marine. (The Coast Guard had yet to suffer a local casualty and the Air Force was still connected with the Army.)

Harold Phillips White

A veteran of World War I, Harold P. White reenlisted after the attack on Pearl Harbor. A member of the Merchant Marine, he died when his ship was torpedoed on June 5, 1942.

His widowed mother, Gertrude White, lived at 1545 Sacramento Street and her son’s name and star was set on the corner of Sacramento and Hyde Streets.

Sergeant Mitchell Small

A gunner on a bomber, Small was killed in a flight over Europe and his body lost behind enemy lines. His marker was placed on the corner of 45th Avenue and Geary Boulevard near the home of his mother, Lillian Pappas, who lived at 433 45th Avenue.

Sergeant Donald B. Gray

The son of Thomas and Emma Gray, Donald B. Gray enlisted in the Marines and was killed by shellfire at Guadalcanal on October 21, 1942. He was 21 years old.

His gold star sign was put at 18th and Sanchez Streets near his childhood home at 402 Sanchez Street and not far from his alma mater, Mission High School.

Seaman Second Class Kenneth Lee Campbell

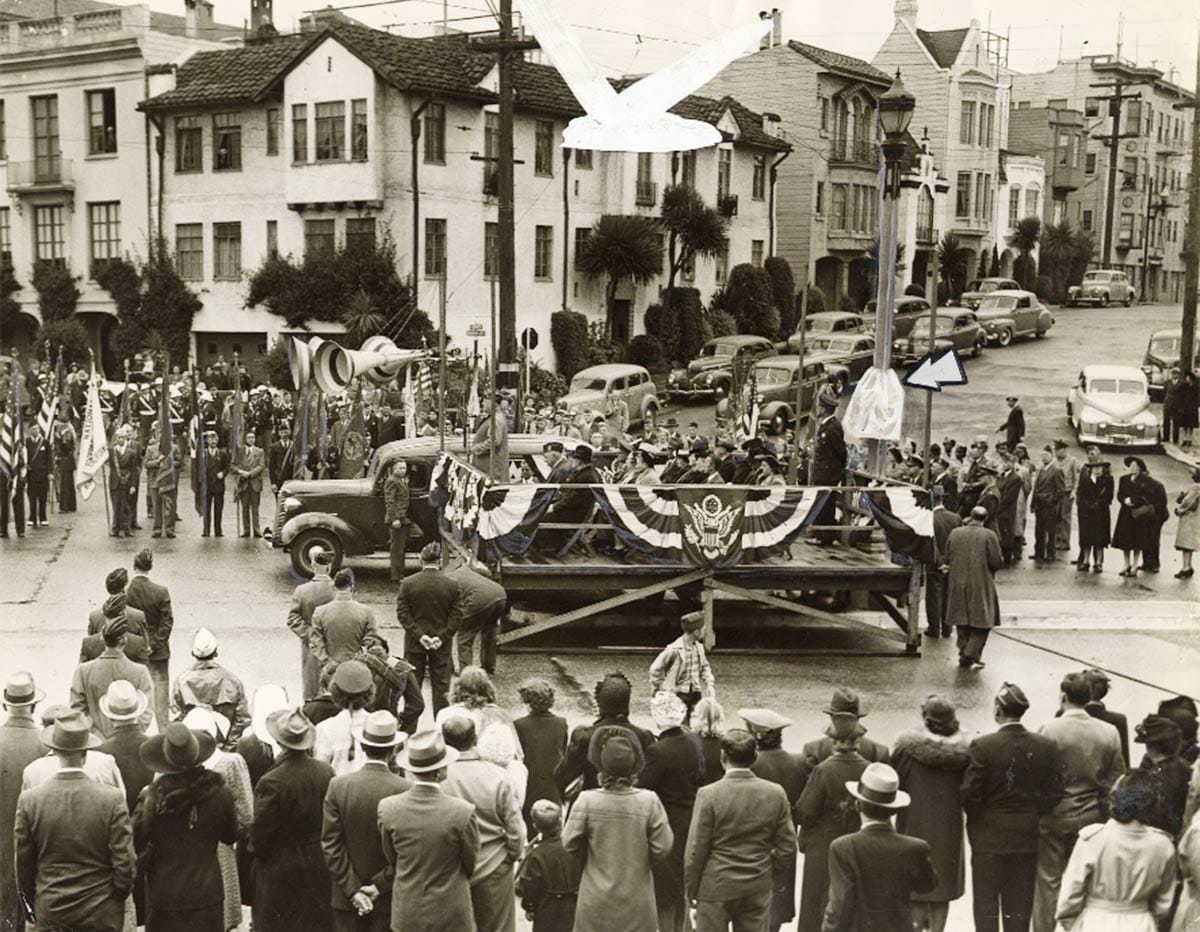

The Memorial Day ceremonies announcing the gold star corner program took place where Kenneth Lee Campbell’s star and name were unveiled at the intersection of Chestnut and Baker Streets at Richardson Avenue, just outside the Presidio.

A graduate of Polytechnic High School who grew up in the Marina District, Campbell joined the Navy. He was killed four months later in the South Pacific when his aircraft carrier was bombed on August 24, 1942.

Since Mayor Rossi was out of town, acting mayor Jesse C. Colman gave the dedication speech to unveil Campbell’s marker and promised that “San Francisco is committed to the erection of signs for all who shall fall in freedom’s cause.”

After the cloth was pulled off to reveal Seaman Campbell’s name, the assembly moved into the Presidio cemetery for more speeches and commemoration.

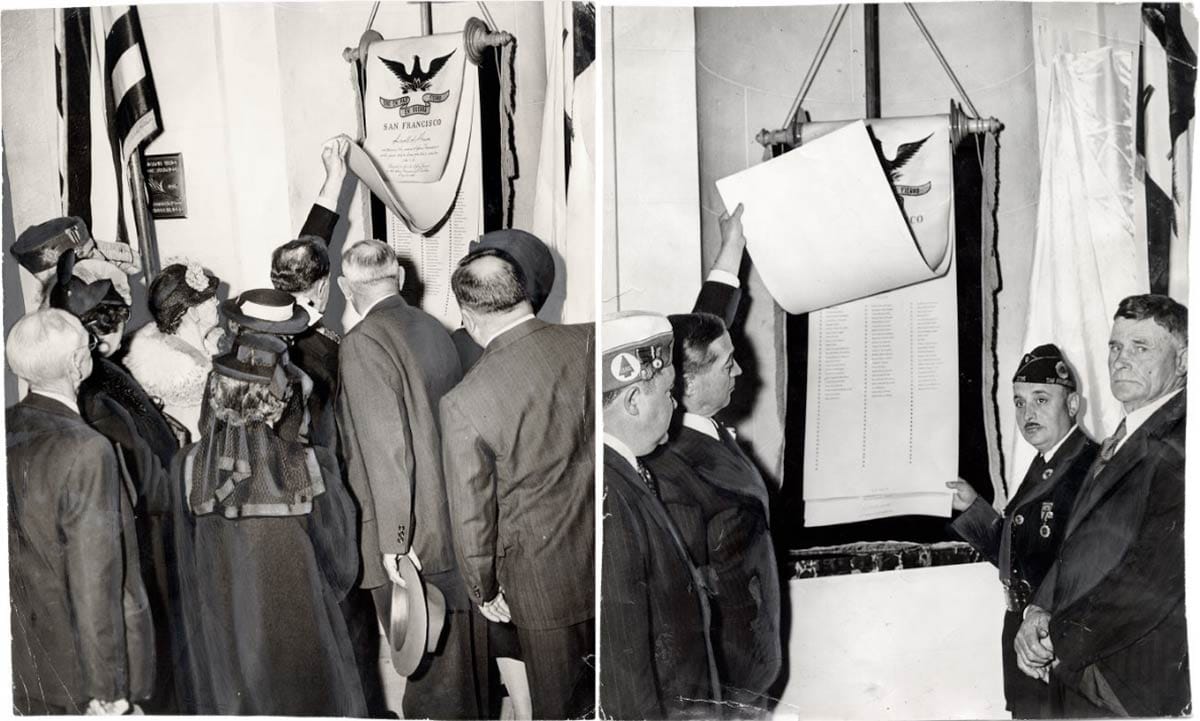

In addition to the gold star corner dedication, an “honor scroll” was presented by the Call-Bulletin newspaper to the trustees of the War Memorial on the same day.

Under the city seal and the Latin motto “Gold in Peace, Iron in War,” the scroll's hanging sheets listed all San Franciscans officially killed or missing in the war. The names were “emblazoned in imperishable lettering” according to the Call-Bulletin.

Installed in “its permanent niche” at the Veterans’ Building trophy room on Van Ness Avenue, its pages held ghostly blank spaces for future casualties.

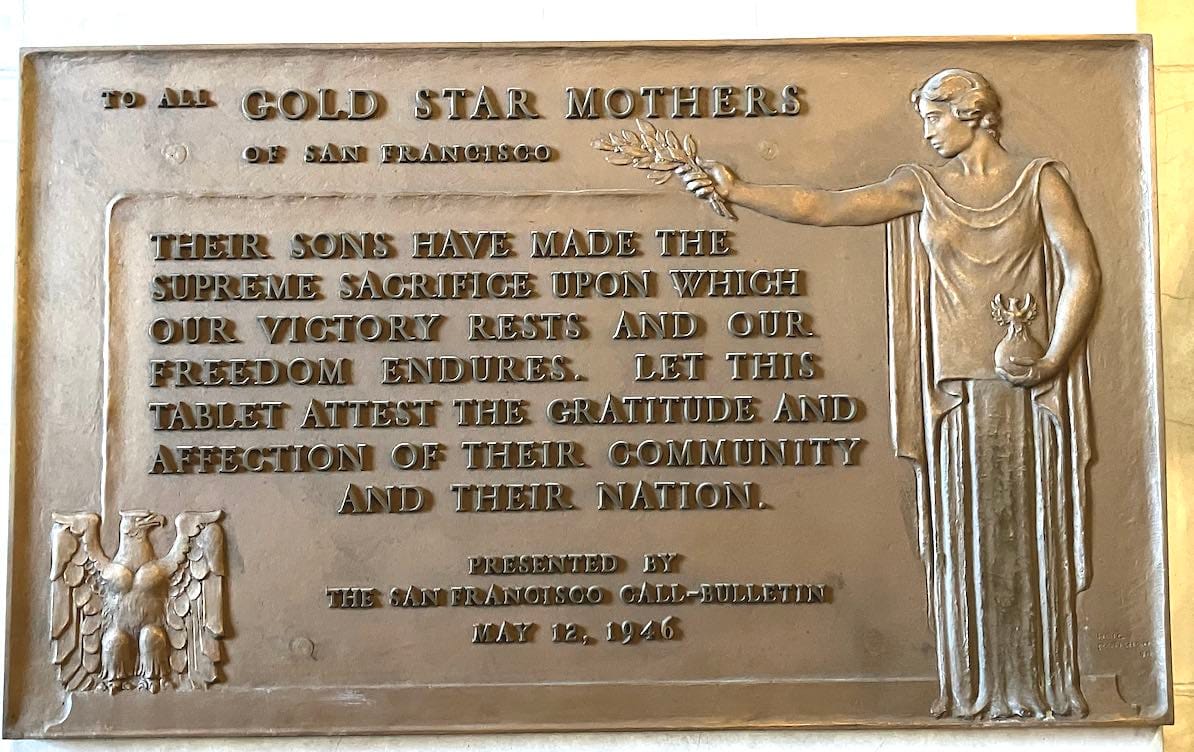

The scroll is probably in the building somewhere, but I wasn’t able to locate it on a recent visit. There is a Gold Star Mothers plaque on the wall, installed in 1946. It is listed as a gift of the Call-Bulletin, so perhaps was meant as a replacement for the scroll:

I don’t know how long the gold star corner signs lasted. The city blamed a lack of labor and materials (due to the war effort) for not creating more signs immediately. I doubt more than the first four were ever made.

Perhaps too many names ended up on that scroll on Van Ness Avenue to make the program practical. Perhaps the idea couldn’t get traction because it was so associated with the Call-Bulletin newspaper in a four-newspaper town. (The Chronicle and Examiner essentially ignored the gold star corners in their 1943 Memorial Day coverage.)

Intersections, light standards, and street signs have changed and been lost over the last 80 years. The traffic island at Chestnut, Baker, and Richardson, where the 1943 dedication ceremony was held, where Kenneth Lee Campbell’s sign was unveiled, is now an archipelago of concrete and a couple of walk/don’t walk signs. No more lamp post.

But Kenneth Lee Campbell’s name is chiseled on a memorial in the Manila American Cemetery and Memorial in the Philippines.

The name of Mitchell Small, lost over Europe, is still emblazoned on a tablet at the Brittany American Cemetery and Memorial in Basse-Normandie, France.

Harold Phillips White has a gravestone in the Long Island National Cemetery in Suffolk County, New York.

Of the four, only Donald B. Gray was able to return home to California. His remains were brought back to his family after the war and reinterred at the Golden Gate National Cemetery in San Bruno on March 3, 1948.

His marker is still there.

Carville show on June 23

I will return to the 4 Star Theater on Sunday afternoon, June 23, 2024, at 1:00 p.m. to give a presentation on one of my favorite San Francisco Stories. Get your ticket today.

And I am interviewing John King, Urban Design Critic for the San Francisco Chronicle, at the Inner Sunset District Green Apple Books (1231 9th Ave) on the evening of Wednesday, June 5, 2024. Come on by.

Woody Beer and Coffee (and Juice) Fund

You do not have to have caffeine or alcohol. You can have beet detox juice with me, as Dave F. (F.O.W.) did at Up For Dayz on Polk Street. Like good 2024 San Franciscans, we talked about AI large language models and local history.

When are you free for a beet juice? I have Woody Beverage Fund dollars to spend lavishly on you.

Sources

“10 Northern California Men on Casualty List,” San Francisco Examiner, February 28, 1943, pg. 20.

“Hero Memorials Dedicated,” San Francisco Call-Bulletin, May 31, 1943, pg. 1G.

“Memory of S.F. Sailor Hero Perpetuated,” San Francisco Call-Bulletin, May 31, 1943, pg. 5.