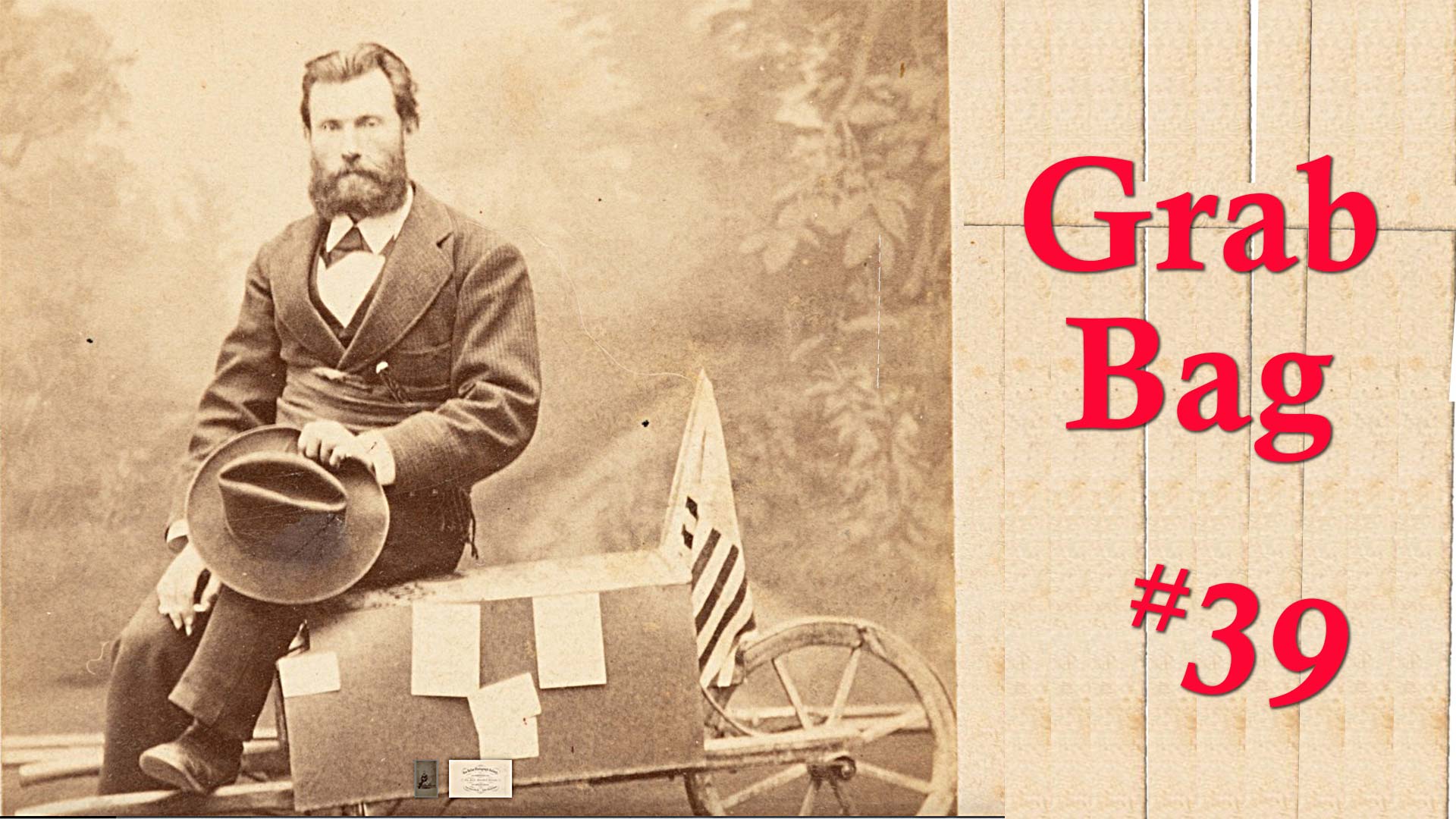

Grab Bag #39

Some odds and ends spotted on recent walks around the Western Addition, Woody on jury duty, and the story of the wheelbarrow man. All in all, kinda strange, but, hey, you knew what you were signing up for.

If you owned this house at 2009 Buchanan Street how could you not paint some words of wisdom on the gable scroll?

Something noble in Latin seems appropriate, maybe “Please don't block the driveway” or “Clean up after your dog” (Tersus sursum post te canem).