House Cleaning Day

On March 3, 1907, San Francisco gave its rubble-strewn streets a good sweeping.

Ho hum, just another historical photograph of a group of men clearing a rubble-strewn street after the April 18, 1906 San Francisco earthquake. That’s what I thought.

But these men look a little too well dressed for laborers: nice hats and ties, watch chains, clean shoes. The scene is Front Street near California Street, with the offices of Ehrman Bros & Co. in the background. Did the cigar-importing firm put its employees to work as street muckers? And some of them are using... brooms?

My friend and researcher John Freeman tipped me off to the story here: “These photos are from March 3, 1907, ‘House Cleaning Day,’ a day set aside for volunteers to join together to shovel debris off the streets, and sweep them clean, with the intention to boost community spirit and show the world that progress was being made in reconstructing San Francisco after the 1906 catastrophe.”

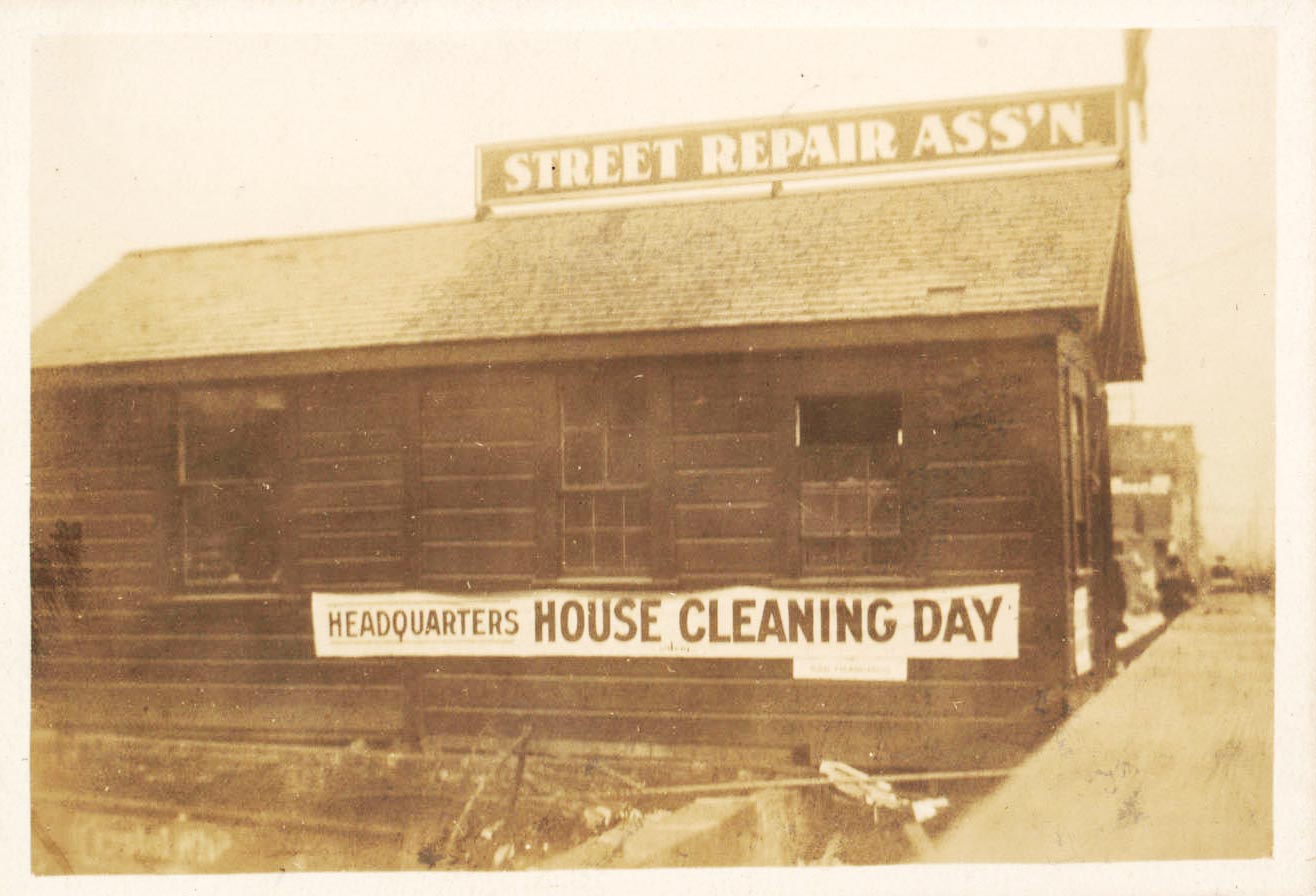

House Cleaning Day was concocted by the Street Repair Association, a group led by city teamsters. The pitch was a day of service in which “merchants and their employees, labor unions, teamsters, contractors, and everybody who can assist, will be asked to take up shovel and broom in behalf of clean streets and sidewalks.” The idea was borrowed from Boston’s once-a-year “Spotless Town Day.”

But San Francisco had a bigger job ahead of it than Boston and House Cleaning Day wasn’t just about dusting the mantelpiece. Almost a year after the earthquake and fires of 1906, the clearing of rubble, paving of streets, and general reconstruction downtown was far from complete. Teamsters and the merchants and suppliers they served wanted to be back in business fast, but accommodating horse-driven conveyances was not a priority in the recovery effort.

Railroad and streetcar companies laid rails to haul rubble and began replacing cable cars with electric streetcar lines, but roadways beyond the track beds remained broken, rutted, and debris-strewn. The teamsters could see their concerns weren’t highly prioritized within the city’s Department of Public Works, so they formed the Street Repair Association in January 1907 to lobby for speeding up road reconstruction and clearing the way for horses and wagons.

But how to get the public on their side? The whole city was recovering. There were still thousands of refugees living in parks. Complaining teamsters didn't harmonize with the optimistic post-quake boosterism San Francisco wanted to show to the world.

The teamsters came up with a campaign that sounded more accessible and homey: House Cleaning Day.

No one is against clean streets, which is why litter abatement is often used to support other agendas and divert attention from more intractable problems. London Breed started her tenure as mayor by bringing a broom to public events. The volunteer street-cleaning organization, Refuse Refuse, which formed during the recent pandemic, is now funded by TogetherSF and tied to a political action committee. In five minutes online, one can easily collect a decent number of politicians sweeping and picking up trash—or at least acting like they are doing so. Here, let me try:

House Cleaning Day was planned in a couple of weeks. The city newspapers loved the idea and helped pull city agencies, social clubs, school groups, and teamster-allied unions onboard. Businesses loudly promised to donate their employees’ time. Chinatown merchant Sing Fat pledged a dozen men. Women’s Associations organized luncheons and coffee stations. Horses, wagons, brooms, and shovels were donated. Liquor dealers were asked to close for the day to aid the turnout.

There was no acknowledgment of the irony that this massive cleaning day was organized in benefit of horse teams which could drop thousands of pounds of dung on city streets each day.

Circulars were sent to residences across the city reading: “It’s up to you. Why? Because: This is your city; these are your streets; this is your business—and if you don’t help to improve you own property, who will? Roll up your sleeves and help. Tidy up your front yard; sweep off your sidewalk; clean your street. Everybody is working—do your share.”

Not everyone wanted to give up a day off to sweep a gutter and city pastors were decidedly put out having one of their Sundays taken away. Rev. George E. Burlingame of the First Baptist Church called the idea “an injustice to the workingman, a transgression of divine law and a violation of the laws of the State of California.”

The San Francisco Call rejoined that the event was voluntary: “Let every man feel that he is giving such help as he can give, as free as the air of heaven, with absolutely no strings on his desire to work a whole day, a half-day or a few hours.”

Even so, on the day of the event, sermons were given against it and scornful Industrial Workers of the World members handed out cards reading “Wanted, 10,000 suckers.”

House Cleaning Day succeeded as a public relations campaign for the Street Repair Association even if—as with modern-day politicians holding brooms and wearing hardhats—the day’s work was mostly performative.

Because again, who is against clean streets? Despite a lack of support from any Super PAC, I am now inspired to give my front gutter a good sweep today.

Woody Beer and Coffee Fund

Great thanks to Joel B. for his support of the Woody Beer and Coffee Fund! There's been some real debate in the “Friends of Woody” community on whether the Woody Beer and Coffee fund can be used to purchase tea or hot chocolate. As this enterprise is a benevolent dictatorship (if not a theocracy) I have decided any beverage is eligible. Let me know when you’re free to join me.

Sources:

“Draymen Plan to Repair Streets,” San Francisco Call, January 11, 1907, pg. 9; “Propose City House Cleaning,” San Francisco Chronicle, February 12, 1907, pg. 7; “Everybody Willing to Aid in Cleaning City,” San Francisco Chronicle, February 16, 1907, pg. 5; “Suggest That Saloons Close,” San Francisco Chronicle, February 20, 1907, pg. 3; “Organize for House Cleaning,” San Francisco Chronicle, February 18, 1907, pg. 2; “Protests Against Work on Sunday,” San Francisco Chronicle, February 18, 1907, pg. 2; “Teamsters Offer Services in Cause of Clean City,” San Francisco Call, February 19, 1907, pg. 16; “Try to Discourage Zeal of Street Brigade,” San Francisco Chronicle,March 4, 1907, pg. 2.