Ingleside Flight

Real and would-be aviators in San Francisco's Ingleside neighborhood in the early 1910s.

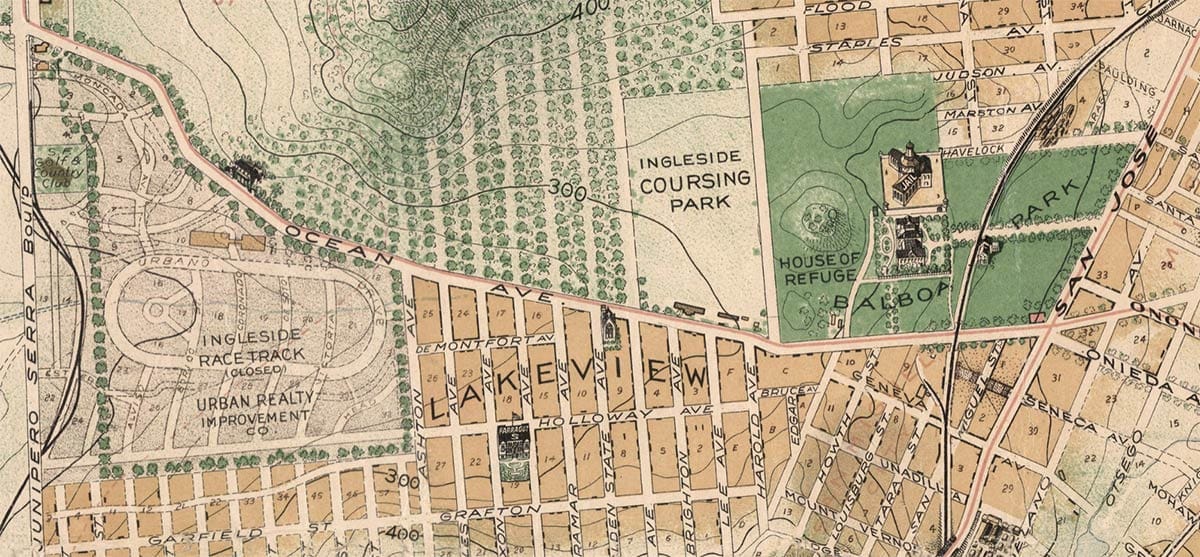

Thinking about the imminent 1,100-unit housing project at the old Balboa Reservoir site, formerly the Ingleside Coursing Park, made me think of this article I wrote for the Ingleside Light back in 2011. I enjoyed reading it again and thought you might too.

Flying is a commonplace miracle today.

Perhaps a thousand airplanes and jets escape the bounds of earth each day, carrying human beings into the realm of eagles and angels.

Most people take our ability to travel by air for granted, while at the same time understanding that the design, construction, navigation, and piloting of these giant metal machines is the work of scientific expertise and engineering beyond the average passenger.

But one hundred years ago, in the first decade of man’s ability to soar, our attitudes and understanding were the reverse: flying was a wonder and the expertise to do so more egalitarian.

Less than ten years after the Wright Brothers made the first controlled, powered, and sustained heavier-than-air flight, many of the makers and pilots of airplanes and gliders were bicycle repairmen, hobbyists, and teenagers.

In the Sunset District, young men built gliders to launch from the high points of the sand dunes. Fifteen-year-old twin brothers Willy and Arthur Gonzales constructed and flew a biplane of their own design over San Francisco’s Richmond District in 1912.

The Ingleside District had its own aviators and would-be flyers. Off Ocean Avenue a former newspaper man ran a secret project to build a transcontinental airship. And up the road, exhibitionist daredevils cavorted over in the sky just west of today’s City College, and carried some of the country’s first airmail.

Secret Airship

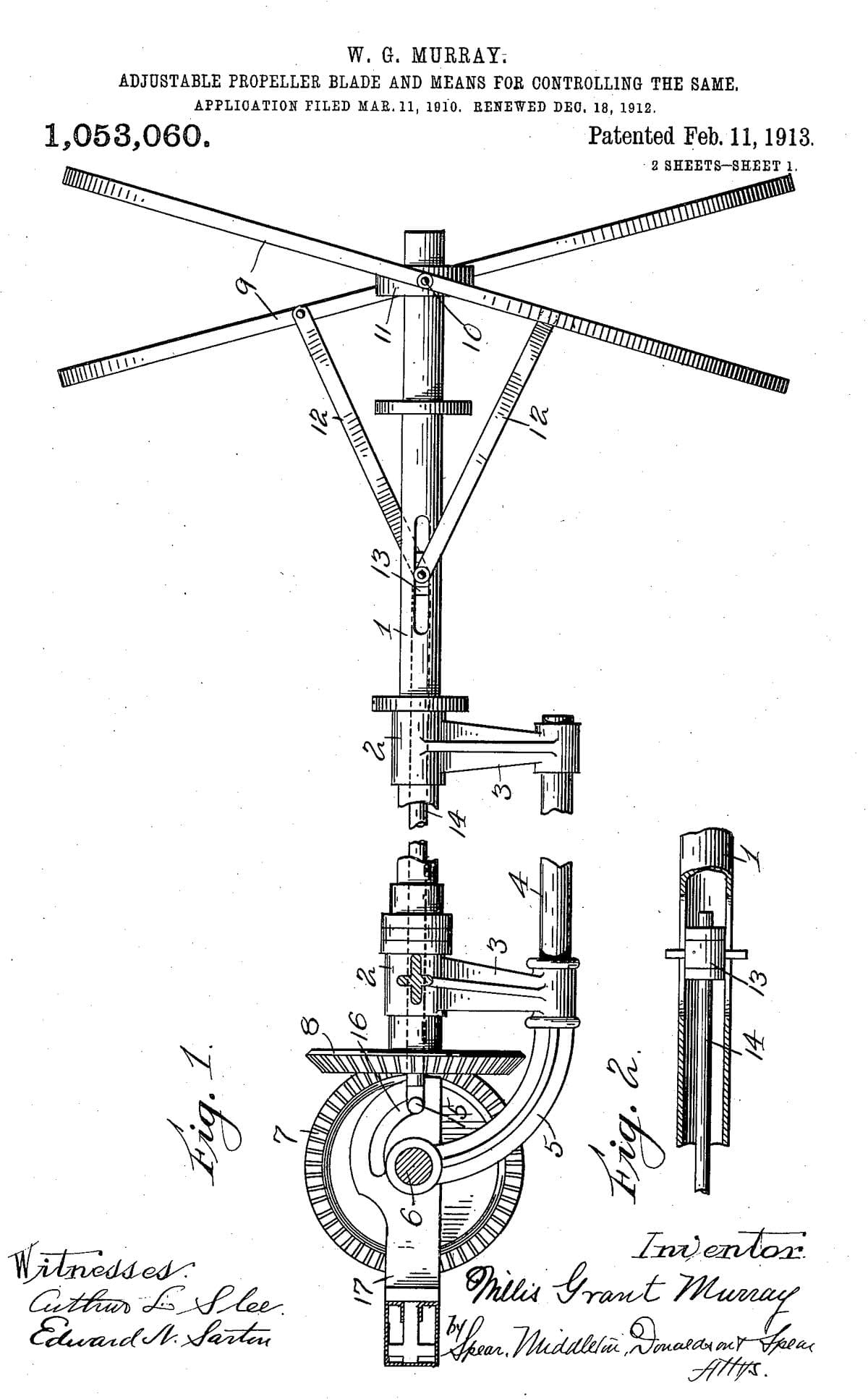

Willis Grant Murray said he had good reason to keep his invention secret. Men interested in long-distance commercial flights had invested $100,000. Government officials were (supposedly) enthusiastic. To have his design details stolen would be catastrophic.

So Murray rented space at the closed Ingleside Racetrack (the site of today’s Ingleside Terraces neighborhood) and built his secret flying machine in a gully out of view of passersby.

But the former newspaper man understood some media attention was necessary, if only to attract more investors. He granted an interview to a San Francisco Call reporter in December 1910.

The reporter had a difficult time describing Murray’s invention, writing that it was “hardly nameable.”

The airship combined elements of the biplane, the dirigible (gas bags were used as ballast, but not to lift the machine), and the helicopter, with three automobile engines driving two fourteen-foot, two-blade propellers at each end.

A deck beneath the superstructure was intended to hold five crewmen and up to ten passengers and had aluminum boats attached as skids in case of a sea landing.

Murray was a confident sort. He calculated his ship would be able to fly six days and nights without landing, covering some 4,000 miles. He planned to get off the ground by the month of May and, if all went well, fly over the Sierras, cross the continent, and perhaps continue on to Paris.

“It is a great venture. I may say without egotism, the greatest that has been made in America. Nothing has been attempted on so large a scale. Your common bamboo, wire and cloth aeroplane is a plaything beside it.”

After dismissing the reporter, Murray tightened security. He hired men to chase away loiterers and the curious. The Call later noted that it was “doubtful if any government has guarded its secrets […] with more zeal than do the watchman of the airship.”

Ocean Avenue Aviation Meet

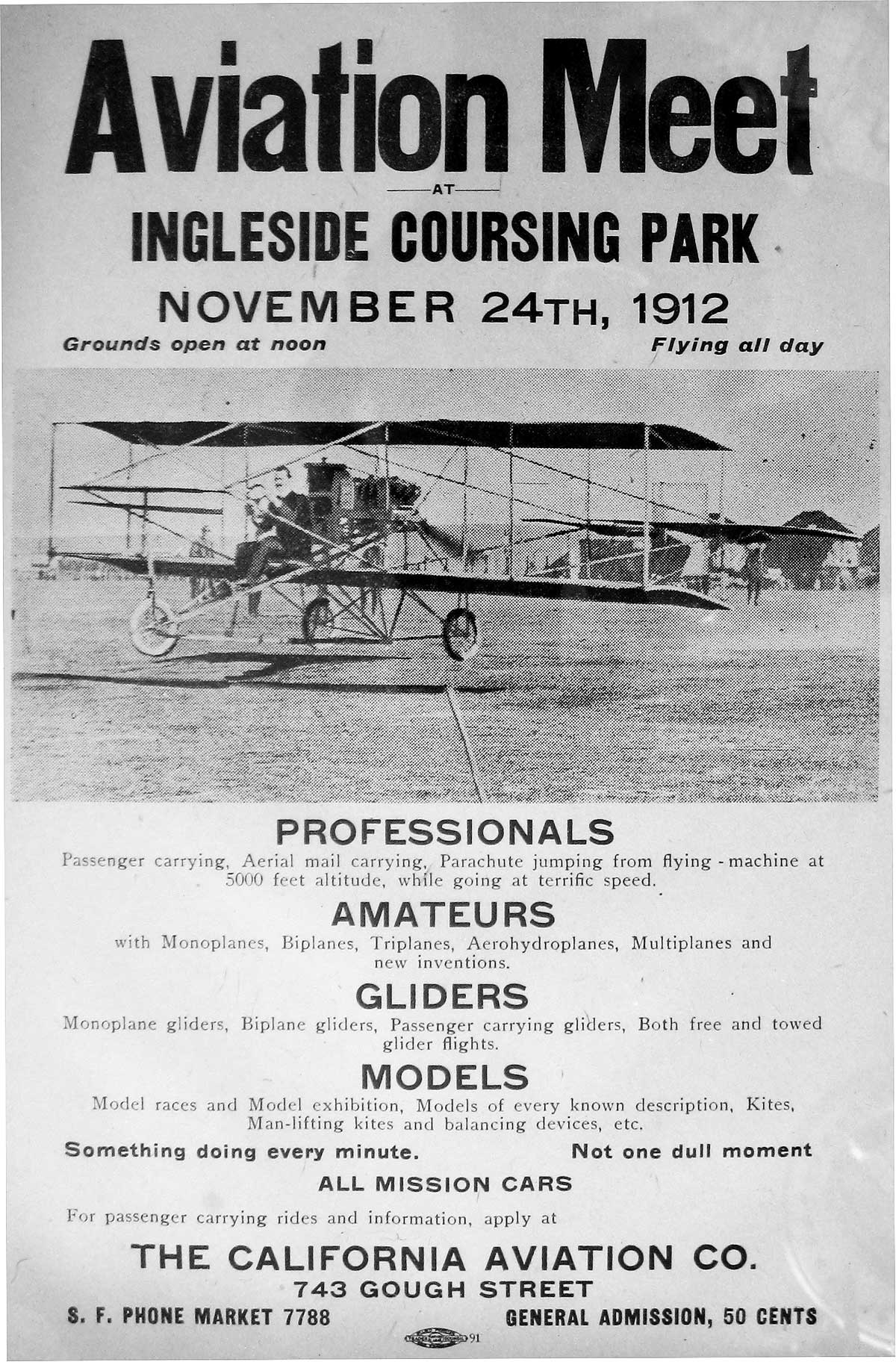

Just a few block away, flyers using Murray’s dismissed common bamboo, wire and cloth airplanes hosted air shows at Ocean and Lee avenues in 1911 and 1912.

The open field of the old Ingleside Coursing Park provided space for take-offs and landings. (Coursing was a sport in which men set their trained dogs to race across fields and catch live rabbits, if you were curious.)

Local daredevil pilot Roy Francis entertained the crowds with flying stunts and speed tests. He gave people rides, including 11-year-old Gladys Grey. The San Francisco Chronicle speculated she was “probably the youngest aeronaut in the world.”

The girl gushed that she had so much fun she wanted to take a plane trip everyday, but farther and higher.

She might have revised her opinion after Francis’ final flight of the day. The aeronaut hit an air pocket and had to make an emergency landing in Sunnyside, clipping an overhead wire on the way down and damaging his rudder.

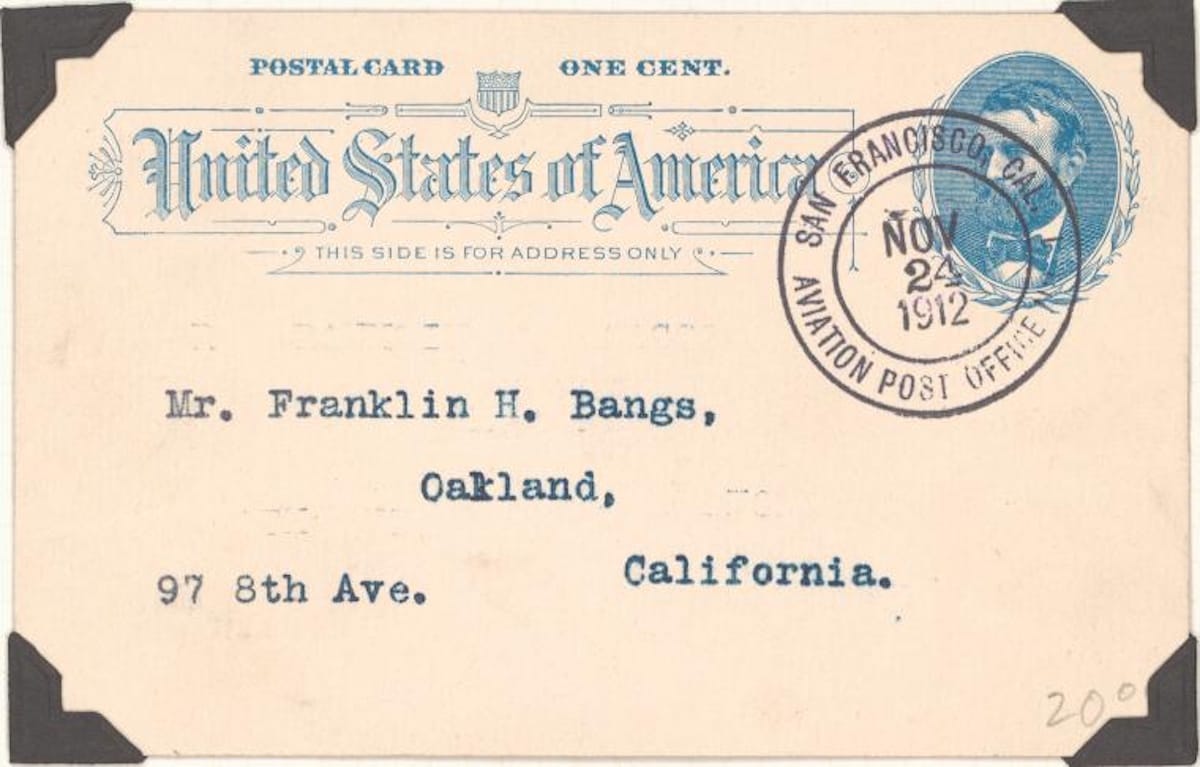

Ingleside Coursing Park hosted an even larger aviation meet on November 24, 1912 in which one of the earliest airmail deliveries took place.

The postmaster opened a substation at the park for the day, “San Francisco, Cal. Aviation Post Office #1,” and processed 47 pieces of mail, mostly postcards.

Pilot Harvey Crawford then carried the bag of mail through the skies to the Presidio. Crawford didn't bother landing; he just dropped the bag to the ground where a man retrieved it to take to the post office.

A bit disappointing that...

While Aviation Post Office #1 was mostly a stunt, airmail had a brighter future than Willis Grant Murray’s flying machine. His predicted May 1911 cross-country flight didn’t happen. In February 1912, his 8,000-pound, 176-foot long, blimp/biplane/helicopter was still earth-bound.

The racetrack property had been purchased. Crews were grading the land and building the first Ingleside Terraces houses.

Murray rushed to get his baby off the ground, but heavy winds kept ripping his hydrogen gasbags asunder and damaging the airship frame. The Murray Airship was a failure and its inventor died in 1919.

The country would have to wait until the 1930s for the first transcontinental commercial flights.

More on Balboa Reservoir site history by the always great Amy O’Hair.

And if you want other flying stories, I have written about Mission District balloon mishaps, balloons in the Presidio, an 1896 UFO, and a Captive Airship camera!

Woody Beer and Coffee Fund

There are lots of new folks subscribing to San Francisco Story who may need a primer. You can toss a tip here to pay for me to have a drink with someone. You can also save your money for that vacation to Luanda, Angola. Population 9 million and the most populous Portuguese-speaking capital city. The choice is yours.

You also can make withdrawals from the fund by letting me buy you a drink. We’ll have fun! Getting our schedules figured out is the only challenge. Let me know when you’re free.