International Settlement

The exotic restaurant row that was the last gasp of San Francisco's Barbary Coast.

Restaurant magnate Pierino “Pete” Gavello, operator of the successful and family-friendly Lucca restaurant of North Beach, had a good idea in 1939.

The Golden Gate International Exposition was about to open on Treasure Island in San Francisco Bay. As with most world fairs, the theme was internationalist—in the words of writer Richard Reinhardt, a tribute of “mystical, physical supra-political Pacific Unity.”

Time magazine called it less poetically, “an exotic chow-chow of the ageless East and the American West.”

Hundreds of thousands of people were expected to descend upon the city. Anticipating these hoards and their thirst for exoticism and foreign locales, Gavello decided he would give the people what they wanted: a honeypot of ethnic and themed restaurants.

He formed an ownership group which bought up most of the property on the 500 block of Pacific Avenue between Kearny and Montgomery streets.

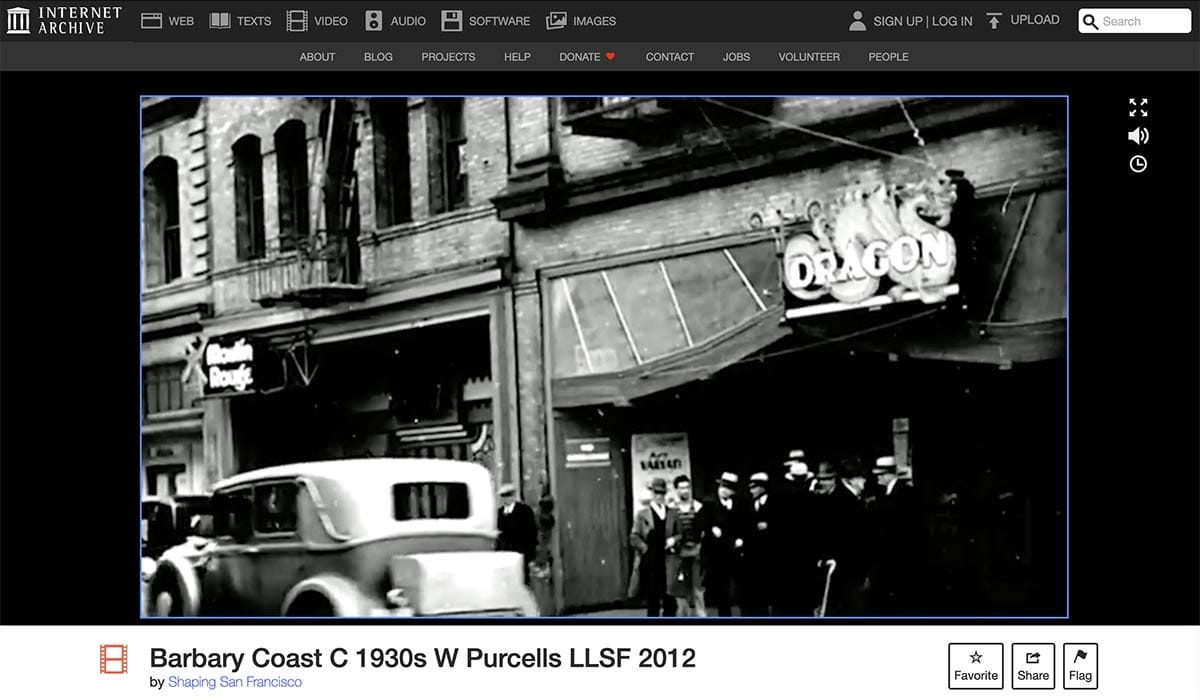

The block had been San Francisco’s Barbary Coast since the Gold Rush days, a red-light district of gin joints, dancing, and sex-work catering to sailors looking for a good time.

Through the 1850s Vigilance Committee era, various vice crack-downs, the 1906 earthquake and fire, the 1917 Red-Light Abatement Act, and even Prohibition, the one-block of “Terrific Street” survived and kept ‘em coming.

Pete Gavello knew the draw of the Barbary Coast, but envisioned a sanitized, tourist-friendly version with white table clothes, classy floor shows, and couples cha-cha-cha-ing in stage-set nightclubs.

He wanted a district where “families and children, the youth and the aged, may mingle in an atmosphere of dignity and refinement.”

The heterogeneous neighborhood between downtown and Telegraph Hill was also called the “Latin Quarter.” Pete’s first idea was to call his block “Quartier Internationale.” He ended up paying tribute to Shanghai’s colonial quarter and went with “International Settlement.”

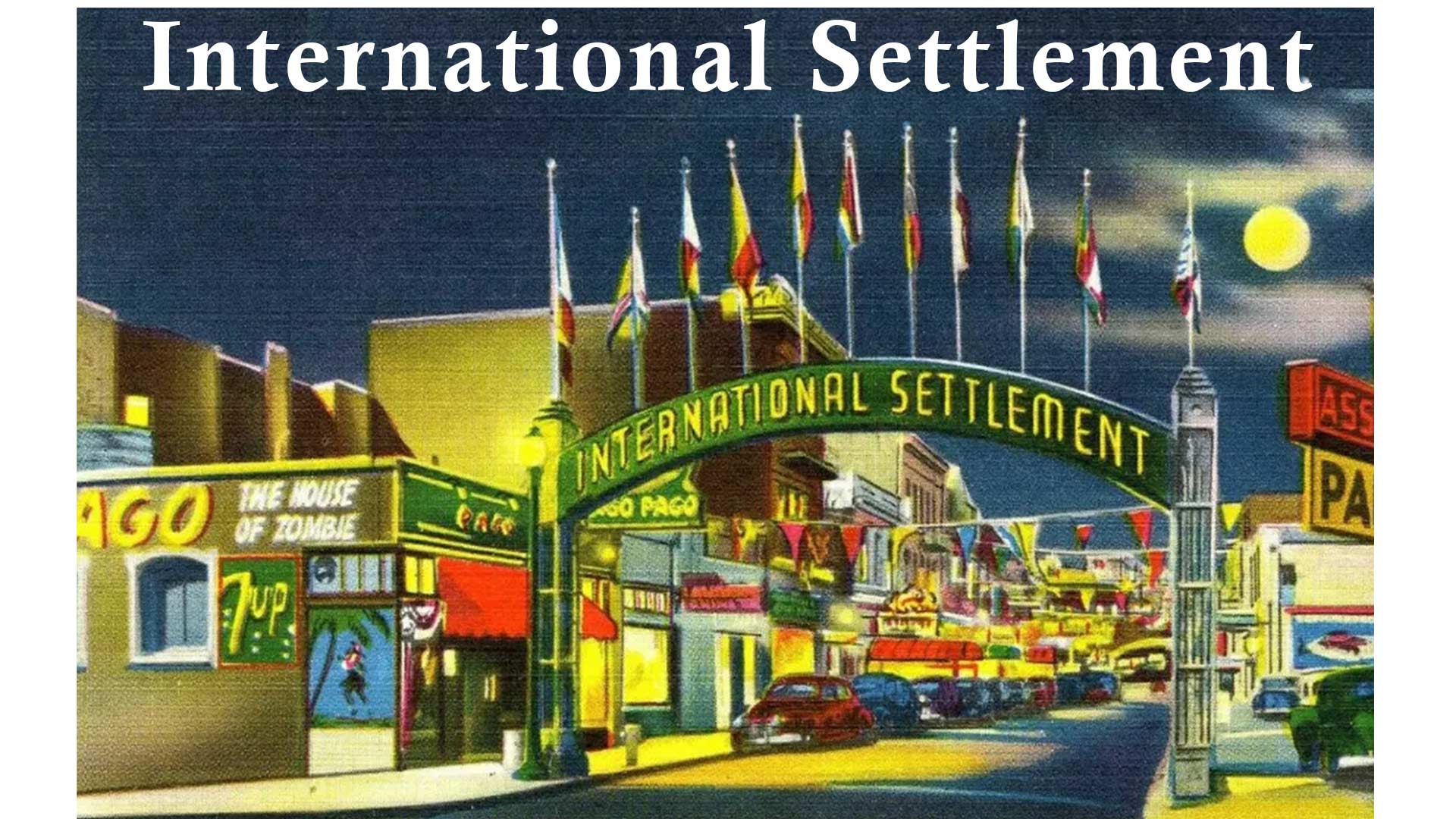

Nothing does a better job of place-making than a street-spanning arch. In the early 20th century, hundreds of small towns, commercial corridors, and neighborhoods went all in on arched signs. (Read my first San Francisco Story about the old Fillmore Street arches.)

Gavello erected one at each end of his block. “International Settlement” was outlined in red neon. Eleven flags from different nations lined the Kearny arch and smaller ones hung on wires up and down the block. You couldn’t miss it if you rode a streetcar or walked on Columbus Avenue between downtown and North Beach.

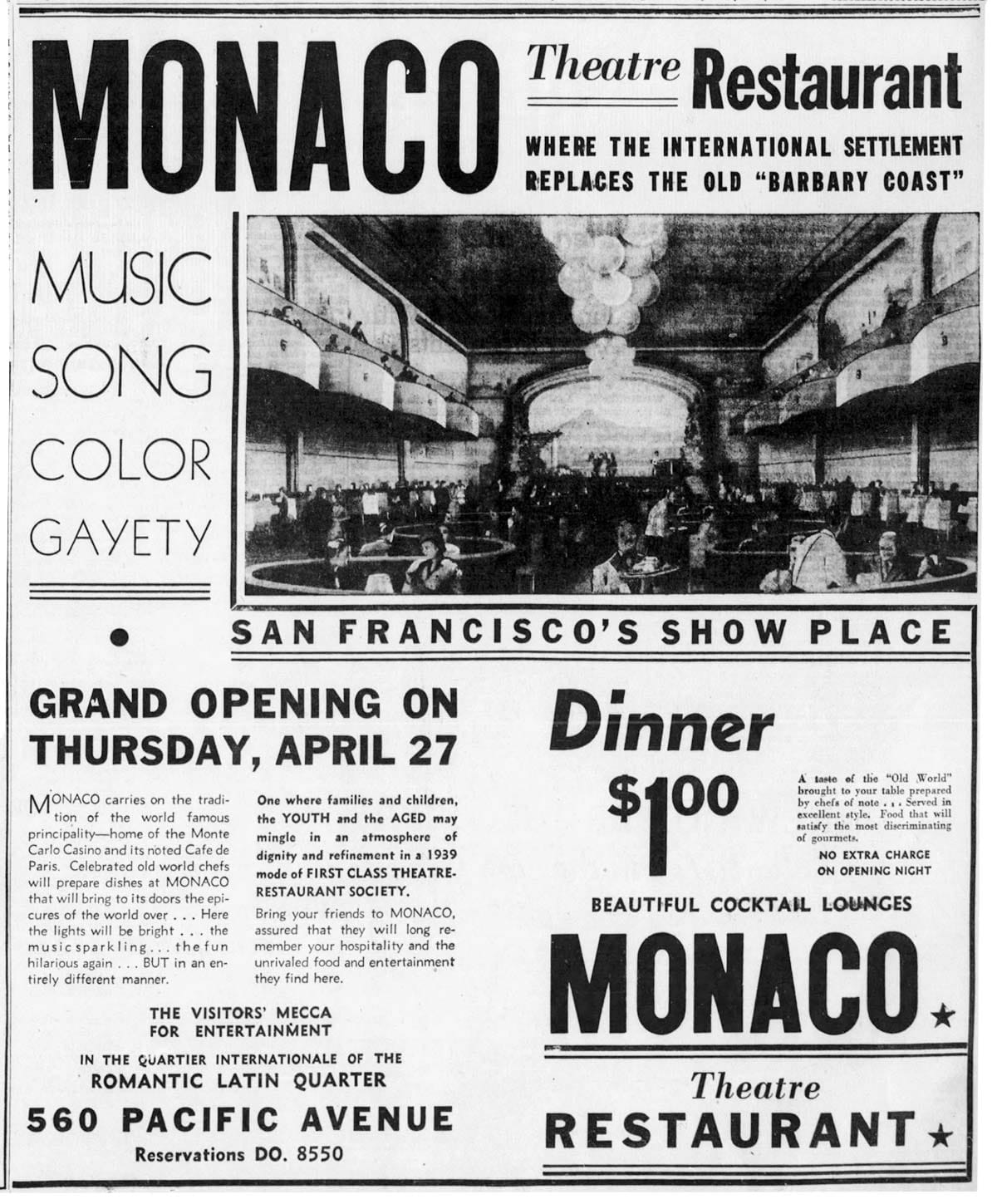

Gavello remade a theater at 560 Pacific Avenue into a Monte Carlo-themed nightclub he named the “Monaco.” He put his son Elmer in charge alongside experienced North Beach merchant George Perasso.

The Monaco, “authentically appointed and decorated with musicians, singers, and dancers in old-country costume” put on three floor shows nightly and was an instant hit when it opened in April 1939.

Dinner was just $1. The real money came from alcohol sales: the Monaco had bars on both the main and mezzanine level of the old theater.

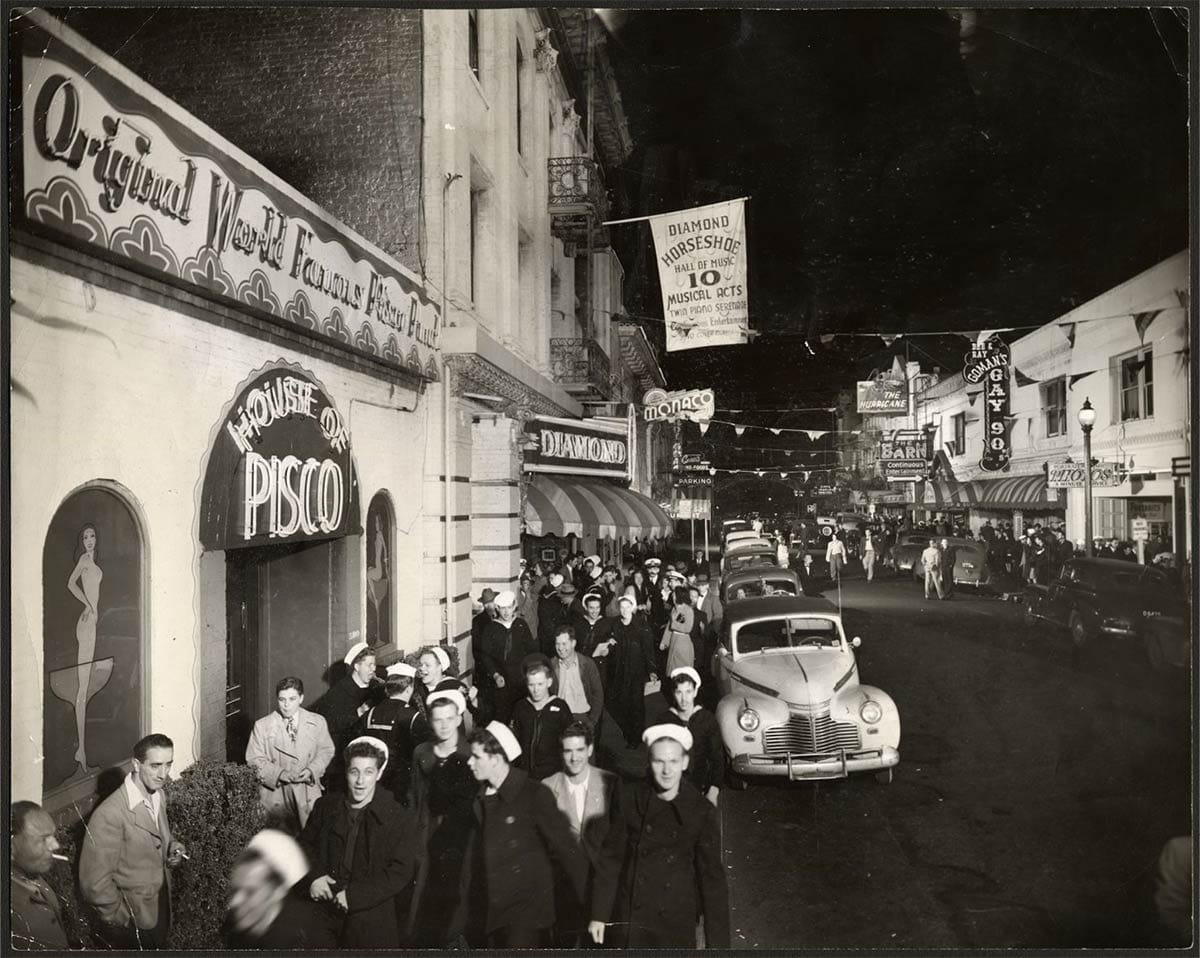

From there the Settlement filled in quickly. The Hurricane and Pago Pago both went for a South Seas theme with grass-hut décors and Hawaiian hula shows. La Conga at 532 Pacific acted as the city’s Cuban outpost, advertising “native dancers and singers.”

American history, or perhaps mythology, was also heavily represented. The Covered Wagon had artist Don Clever mural-ed up the walls with Wild West scenes. Small frying pans inscribed “Stolen from the Covered Wagon” were given to female patrons as souvenirs.

The Barn was a county comedy shop. The Showboat took the riverboat vibe. The House of Pisco (named after the famous early California cocktail) and Ray Goman’s Gay 90’s paid tribute to the block’s bawdy Barbary Coast roots, albeit with acts of a tamer vaudeville style.

The Settlement did well during the fair, but business really boomed when the United States entered World War II when war workers and members of the armed forces swamped the city. Every bar, restaurant, and nightclub made good money.

Ironically, the return of the sailors pulled Pacific Avenue back to its red-light roots. Gavello’s lease-holders and neighbors begin shifting their business models to give the military men what they wanted: dance halls, burlesque shows, and maybe just a touch of prostitution.

Gavello held the line at his place, but the honky-tonk had returned to Terrific Street.

The end of the war brought back American prudishness.

During the conflict—when men were leaving to fight, possibly die, in the Pacific; when you needed woman to build ships; when racial and social strictures were loosened to keep the country together—it was all very fine to look the other way. Those days were now over: time to get married, move to the suburbs, and have babies.*

Water finds its level; in a way, vice does as well. Pacific Avenue was still a draw with its old Barbary Coast reputation. With the respectable folks gone, it soon again became the city’s high-profile strip of sin (along with neighboring Broadway).

City police battled a resurgent B-girl economy. The State revoked liquor licenses of ever-changing disreputable outfits. The Armed Services put much of Pacific Avenue on their banned lists.

Gavello tried to turn things around. He gave up on the Monaco and relocated his family-friendly restaurant Lucca to the space at 560 Pacific Avenue.

But by 1957, he was done with the whole thing. “There will be no more monkey business in this block,” he told the press.

Nearby, a handful of decorators had recently found success turning a row of old warehouses into a wholesale showroom and design district they called “Jackson Square.”

Sounded good to Pete.

Down would come the neon signs and the arches and all signs of red-light life. Son Elmer became a developer, building suburban homes in Sunnyvale.

International Settlement had one last shining moment in the spotlight by being spruced up for the film “Pal Joey” with Frank Sinatra, Rita Hayworth, and Kim Novak. (Read more at the excellent reelsf.com.)

In the early 1980s, decorator showrooms and antique dealers made way for lawyers’ offices. During the 1990s, multimedia and early tech moved in. Now the old brick warehouses have become a hot-spot for the two-letter modifiers of our time and place: VC investors and AI companies.

Is there anything left of International Settlement in sleepy, tree-lined Pacific Avenue? There are bits and pieces, including two wonderful “Thomassons” (read Grab Bag #45 for that definition) on the western corners of Pacific Avenue and Montgomery Street.

Modern fire engines likely wouldn’t allow the reconstruction of the “back” arch sign, which in later years read “Thank you! Come again,” but it would be a nice sentiment.

More on Jackson Square, including "John's Rendezvous."

* An illustrative story left in the comment section of this article: “My parents met in the International Settlement in 1948. Dad was a merchant seaman on shore leave and Mom was a burlesque/chorus line dancer working in several clubs. [...] They got married and I came along in early 1951. By the mid-50s, Dad had become a ‘land lubber,’ selling Hoover vacuums door-to-door. Mom retired from it all and we moved to the burbs. I call them ‘The Sailor and the Dance Hall Girl.’”

Woody Beer and Coffee Fund

Kick into the make-Woody-be-social-fund so that I don’t spend every day staring at screens, typing, or writing bad poetry about death and old cars. And let me know when I can buy you a drink!

Sources

“Old Barbary Coast to Get New Café,” San Francisco Examiner, August 7, 1938, pg. 12.

“For S.F. Guests: A $1,000,000 Show Spot,” San Francisco Chronicle, December 30, 1938, pg. 4.

“Opening of Café to Mark Barbary Coast Passing,” San Francisco Examiner, February 21, 1939, pg. 27.

Ivan Paul, “Around Town,” San Francisco Examiner, January 26, 1940, pg. 16.

“An Old Tradition Lives Again,” San Francisco Chronicle, January 28, 1940, pg. 14.

“News of S.F.’s Hotter Spots,” San Francisco Chronicle, August 30, 1943, pg. 10.

Memory of the parents meeting in International Settlement comes from Dario Oakley at ReefSF.com

Orr Kelly, “Lucca: A Family Place,” San Francisco Chronicle, May 15, 1950, pg. 31.

Ernest Lenn, “New Decorating Center to End Barbary Coast,” San Francisco Examiner, June 5, 1957, pg. 1.

Richard Reinhardt, Treasure Island: San Francisco's Exposition Years (San Francisco: Scrimshaw Press, 1973)

Bernard C. Winn, Arch Rivals: 90 Years of Welcome Arches in Small-Town America (Enumclaw, WA: Incline Press, 1993)