Lake Merced Roadhouses

San Francisco's Lake Merced was the home of roadhouse resorts from the 1850s to the early 1880s.

The north side of San Francisco’s Lake Merced is a great place to find a house with two garages, a good school for your kids, or to do some bird-watching. Its residential character means it’s not a great place to find a drink.

(Unless, of course, it’s a late night in 1983 and you are meeting a bunch of teenagers at “the circle,” the parking lot at the end of Sunset Boulevard.)

The situation was different in the 1850s and 1860s.

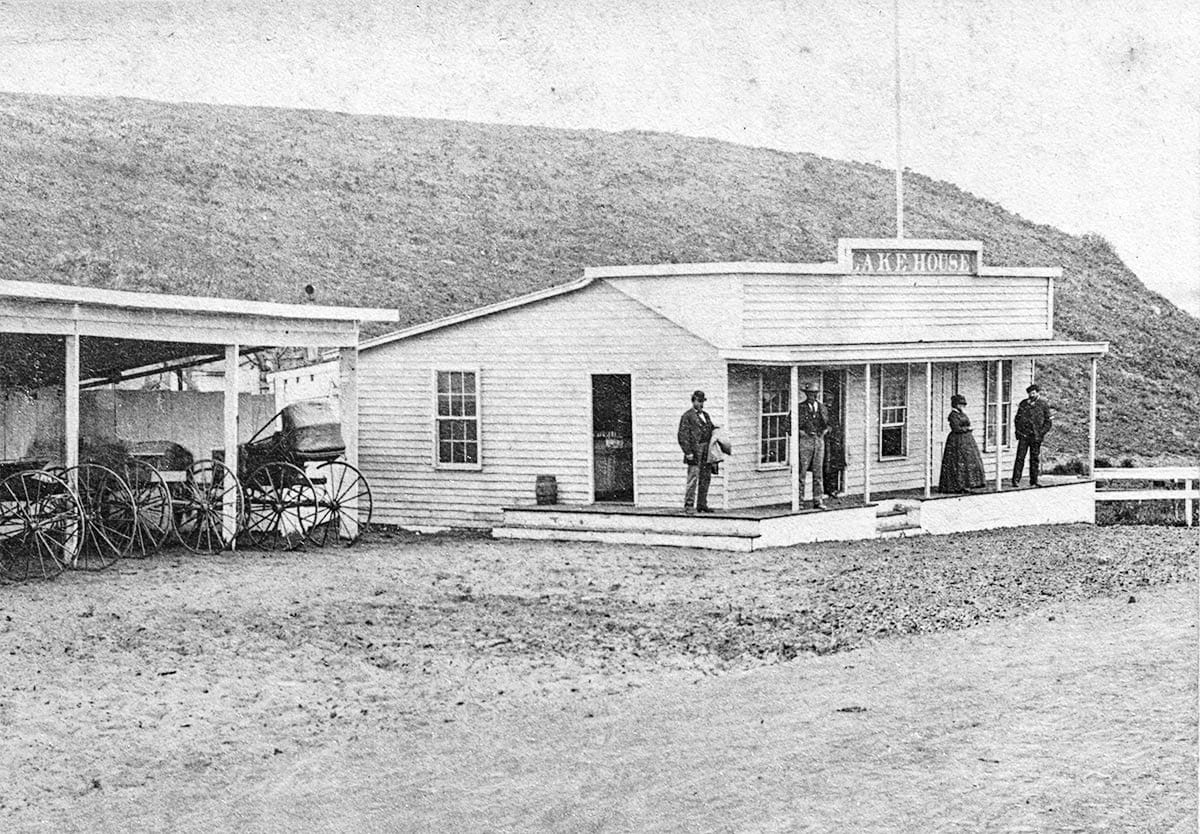

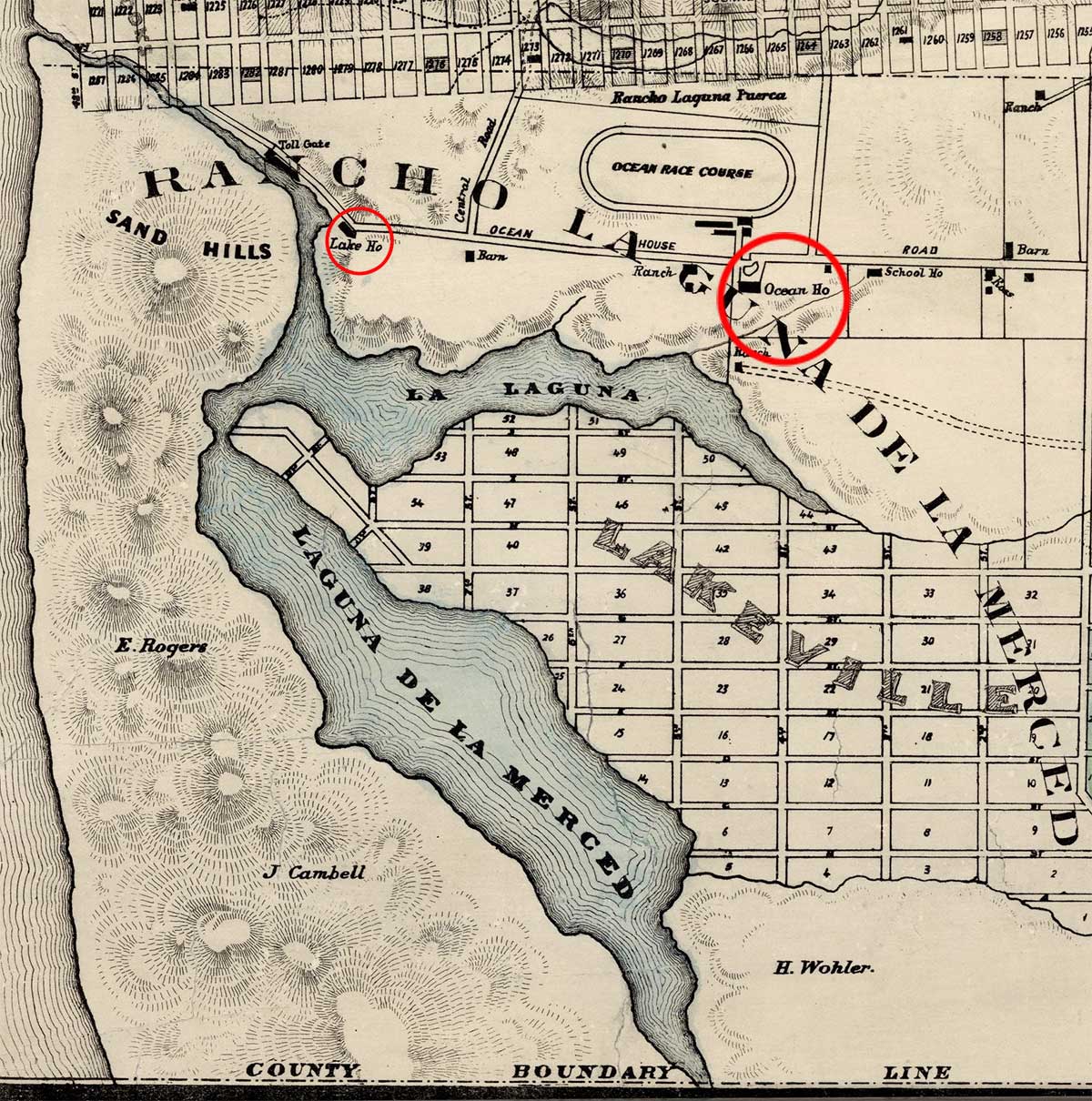

Charles Brown moved a one-story shanty to where the two large arms of Lake Merced pinched together to established the Lake House on the old Rancho Laguna de la Merced in 1853. This institution would move to the north side of the lake when a toll road to the beach was cut through in the early 1860s:

Amenities included a crude bar and a kitchen to serve folks out for a ride to the lake and Ocean Beach.

In early 1854, P. L. White leased the Lake House, expanding and renovating the building, determined (as one newspaper claimed) “to afford our citizens a resort second to none of the kind in the Atlantic States.”

What made a resort? The Daily Alta California explained in 1855:

“Here you will find a lake, and in the lake a boat, and in them both at once you may sail to your heart’s content. You may also roll at ten-pins and pitch quoits till you are tired, or sway in the swing till you get rested.” The purveyor of the house “will furnish you the finest dinner that is possible to provide in California.”

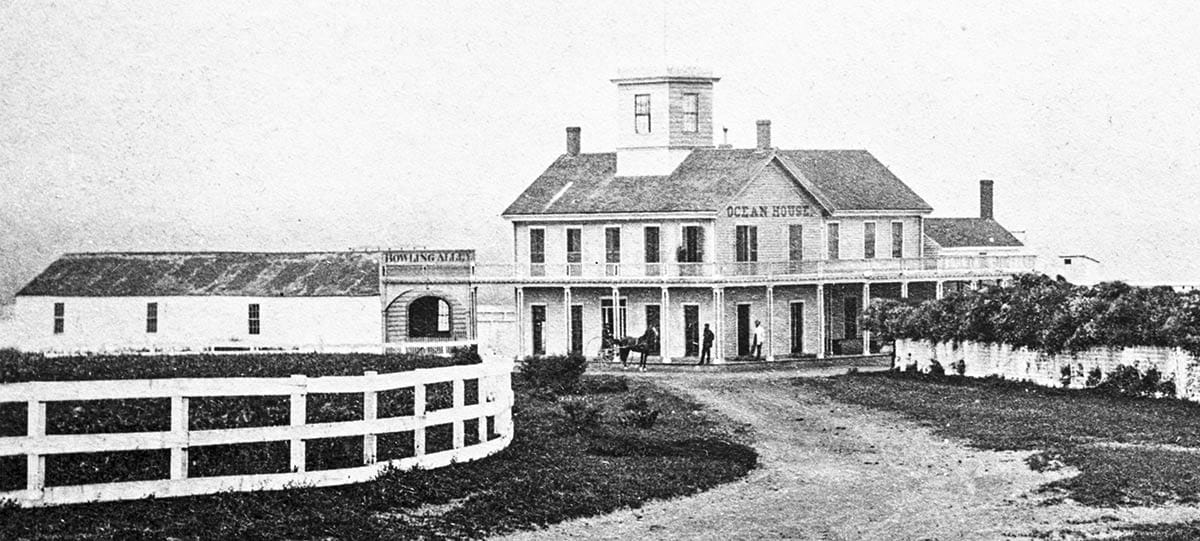

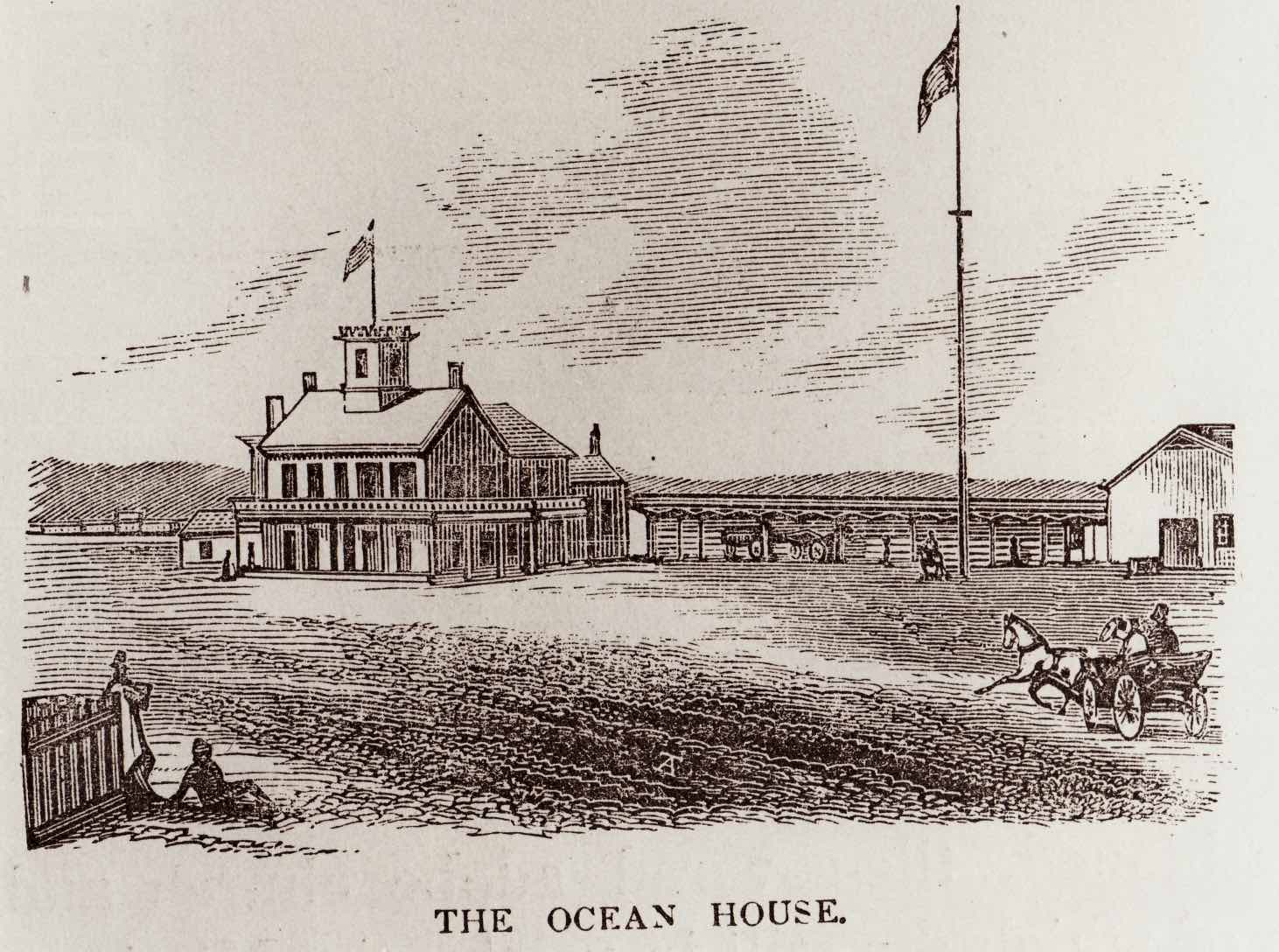

In 1854, the same year the Lake House opened to such high praise, a competitor opened a mile east on the Ocean Road to intercept thirsty customers. Proprietor Joseph W. Leavitt called his place “Ocean House,” and built a grand structure for the era and location.

The Ocean House had dining rooms, parlors, and a billiard salon. The second story had open balconies to appreciate the lake and ocean. Surmounting both was an enclosed view tower. Around the grounds were various out-buildings, cottages, stabling for a hundred horses, and even a bowling alley.

For thirty years, until it burned down in the early 1880s, the Ocean House was a local landmark. It stood just south of the Ocean Road about where Lowell High School is today.

While the Lake House and Ocean House advertised themselves as countryside resorts suitable for family outings, wealthy traveling parties, and “invalids desiring to derive the benefit of the sea air,” their clientele was mostly single men looking for a good time.

Newspaper articles called them “fancy men,” “sports,” and “fast drivers” primed to race horses, drink, and even duel.

Suspects from swindles or robberies downtown were often caught drinking at the Ocean House. While women did occasionally visit the Lake Merced roadhouses, many were characterized as on the shady side.

In 1857, the Daily Globe called the Ocean House “an assignation house on a large scale” and claimed the servants there had been trained to “favor infamous enterprises.”

Smaller establishments along the Ocean Road didn’t bother to aspire to the level of “resort.” The Rockaway House, the Beach House, and a scattering of other nameless stops were little more than one-room bars. The entire bill of fare usually consisted of no more than whiskey or rye in a glass.

In 1864, thinking the Ocean Road’s popularity portended a great land boom, auctioneer and speculator John Middleton tried to sell 160-by-200 foot lots on the eastern side of the lake for a suburb he called “Lakeville.”

The venture was a colossal failure, and Lakeville never became a reality beyond its persistent existence on maps for the next twenty years.

For all their bucolic attractions and press, the lake roadhouses were little more successful than Lakeville.

Fresh lessees and hosts arrived almost every spring at both roadhouses. They’d tout renovations, improvements, and sumptuous new menus.

But the remoteness, the weather, and competition from more convenient public gardens and pleasure resorts in the Mission conspired against steady profits.

And the path to Ocean Beach was not as steadily traveled as, say, the San Bruno turnpike through Visitacion Valley.

The creation of a horse-racing track adjoining the Ocean House brought out thousands of people for big races at its opening in 1865 and then its closing in 1873, but otherwise couldn’t draw the crowds.

The original Lake House was moved downtown to an empty lot on Mission Street near 2nd Street, and later moved again to 7th and Bryant Streets, an object of story-telling for old-timers into the late 1880s.

By 1889, the fun was over. A writer described the Lake Merced area as returning to how it looked when the Spanish arrived at San Francisco Bay in the 18th century, or at least “abandoned to a solitude almost as absolute.”

It would take until the until the mid 20th century for John Middleton’s Lakeville dream to come to suburban fruition with the Lakeside, Lakeshore, Merced Manor, Country Club Acres, Stonestown, and Parkmerced housing developments.

Just remember to BYOB.

Woody Beer and Coffee Fund

It was great seeing more than 400 of you at the Haas-Lilienthal House on Saturday. We had a lot of fun, sold a lot of books, and raised some money for a great nonprofit. What I got out of the whole thing was an immense sense of gratitude to the many, many folks who volunteered their time, energy, and cheerfulness to the day. Thanks to everyone involved!

So, I owe many of you a drink. 😄 Lucky that I have a dedicated fund for just such a purpose. When are you free?

Sources

John S. Hittell, A History of the City of San Francisco and Incidentally of the State of California, (Berkeley: Berkeley Hills Books, 2000), pg. 180. (Reprint of original work, published by the Bancroft Co., San Francisco, 1878).

“The New Lake House,” Daily Placer Times and Transcript, April 27, 1854, pg. 2.

“Suburban,” Daily Alta California, June 8, 1855, pg. 2.

“The Ocean House,” Placer Times and Transcript, June 16, 1855, pg. 2.

“A Heartless Piece of Villainy,” Daily Globe, March 7, 1857, pg. 2.

“Lake Merced, Its Many Historical Associations,” San Francisco Chronicle, December 15, 1889, pg. 8.