The Legacy of Uncle Cliff

Cliff Kamaka ruled Fleishhacker Pool and influenced a generation of Kelly's Cove surfers.

“History back [in San Francisco] should mention Eddie Ukini and Cliff Kamaka, Hawaiians: they were some of the first guys out there.” —Jack O’Neill in the documentary “Great Highway: Journey to the Soul of San Francisco Surfing.”

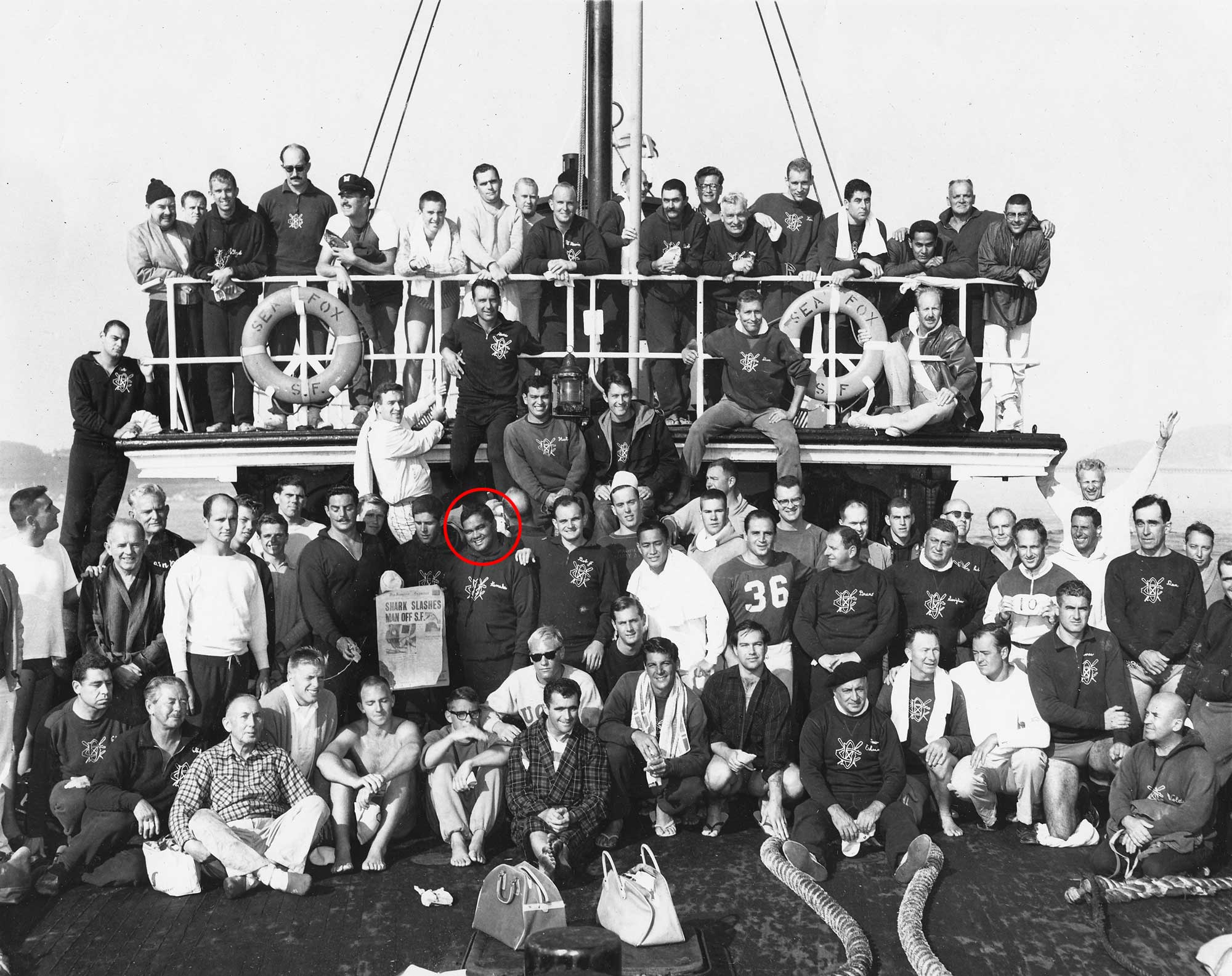

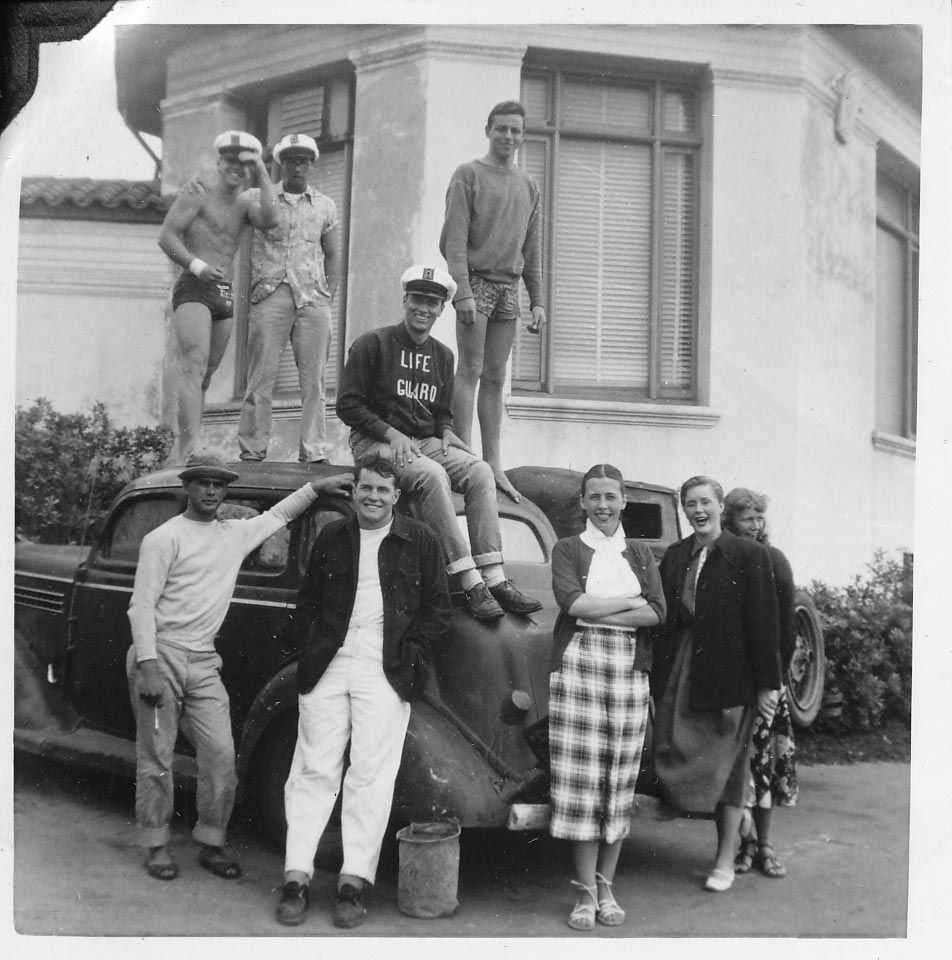

Clifford Kaiakaula Kamaka, born in Honolulu, moved to San Francisco after finishing his service with the Army in World War II. He joined fellow Hawaiian Eddie Ukini to work as a lifeguard at Fleishhacker Pool, the city’s massive public swimming facility at Ocean Beach. From the late 1940s until the pool’s closure in 1971, Cliff would be an inspirational mentor and role model for San Francisco’s developing surf culture.

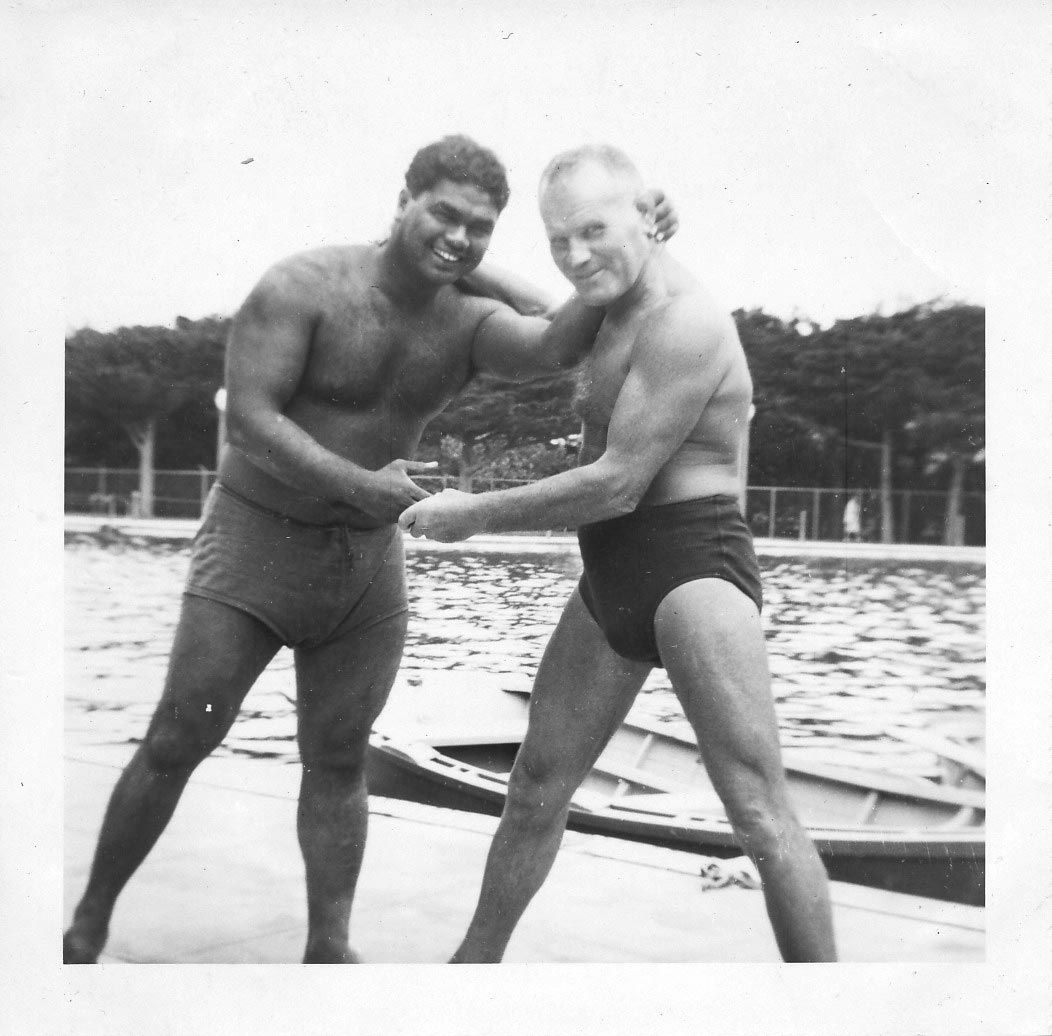

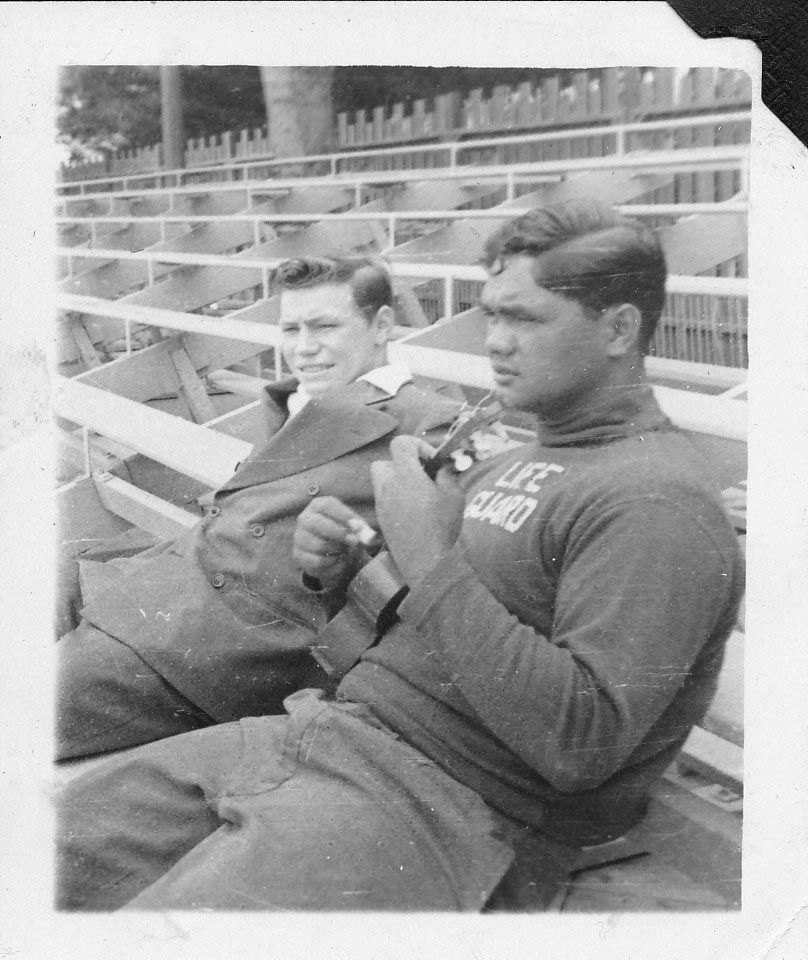

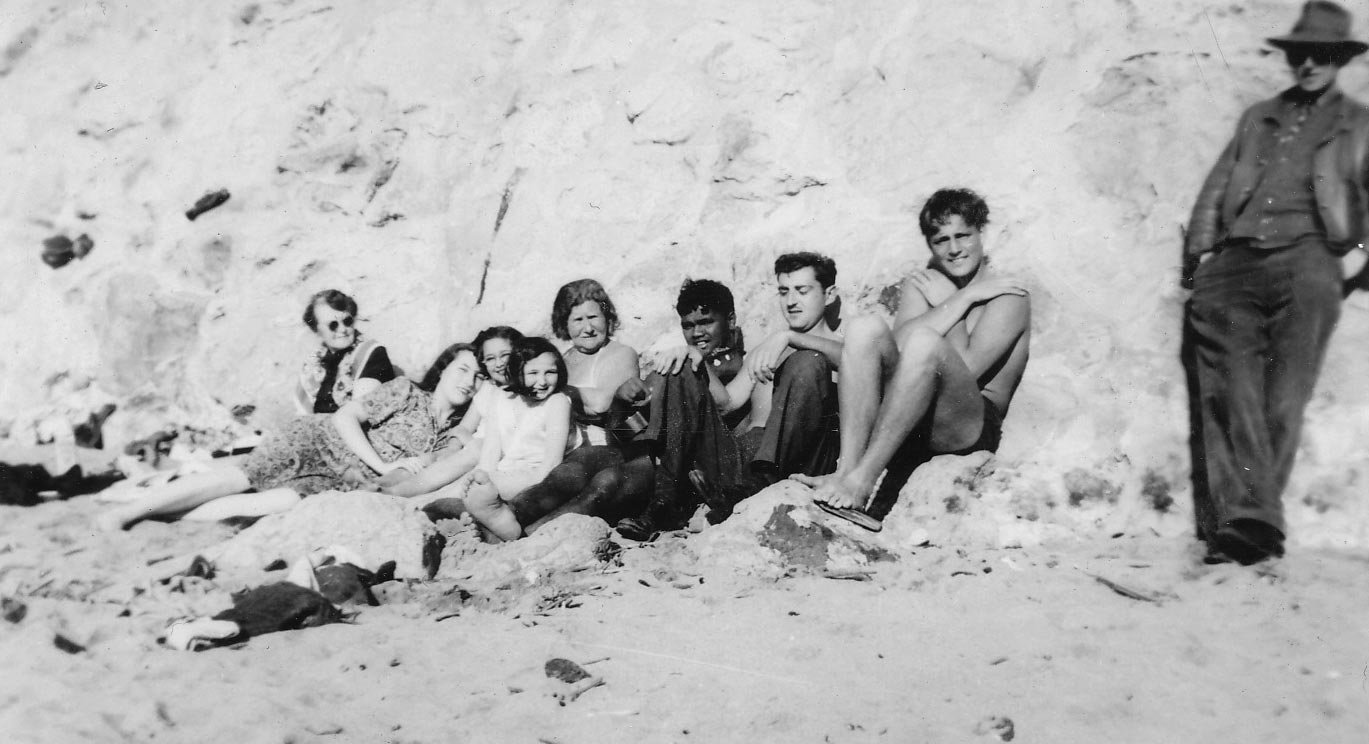

If the smiling young man in the old black-and-white photos was seen on the streets of Los Angeles today many would peg him for a movie star cast in the latest superhero movie. While only 5'7", Cliff was muscular in an era before scientific diets and body-building. He knew judo. He was also handsome, athletic, and composed. To use a modern term, “Uncle Cliff” was chill.

“Cliff was of the philosophy of teaching by example,” Mike Phipps told me. “He was a man of very few words. But his gestures spoke volumes.”

Kamaka could settle down a rowdy crowd at Fleishhacker’s with just a frown and a tilt of the head—no one messed with Cliff—but he was also a lovable guy with a charismatic smile and had true aloha spirit, the Hawaiian extension of affection, respect, and warmth without expectation or obligation.

Mike Phipps knew Kamaka from when he was a kid swimming at Fleishhacker and later as a co-worker and close friend. He remembers how everyone respected Cliff: children who rode on his shoulders in the pool, fire-fighters and police officers who knew he saved more than a few lives at the beach, teens who paid the dime admission just to hang out at Fleishhacker and hear Cliff play his ukulele, and those who learned to body-surf from him at Ocean Beach.

Many of those swimming, running, and body-surfing at the beach with Cliff became important to San Francisco’s emerging surf culture.

Jack O’Neill opened the first surf shop on Ulloa Street just off Lower Great Highway, invented one of the first commercial wet suits, and built a worldwide lifestyle brand. Bill Hickey made some of the best hand-crafted boards out of his Sunset District garage. Fred Van Dyke, legendary big-wave surfer and author, credited Cliff with introducing him to the wonders of the ocean and much more:

“[He] had in him the whole Hawaiian culture, which was beautiful. I was opened up to things I’d never seen in my life.” […] “Cliff showed me daily that surfing was not a sport, but a way of life, a style of living I wanted to make mine forever.”

The idea that swimming or surfing in the ocean was more than a hobby or a form of exercise permeated many in a group of young people who clustered at Kelly’s Cove at the northern end of Ocean Beach. Cliff's aloha spirit mixed with new free-thinking openness about spirituality, human relations, and respect for the natural world.

While there was plenty of partying around auto-tire bonfires in the 1960s, there were also deeper meditations. Riding the powerful, sometimes capricious waves of the Pacific Ocean felt to some a reflection of every man and woman’s personal journey. For many then, and now, surfing went beyond just a metaphor. Surfing became spiritual practice. Surfing was life.

O’Neill and Hickey and Van Dyke contributed to surf culture with their inventiveness, craftsmanship, and physical skill. But Cliff inspired an embodied ethos and relationship to the water and extended acceptance to a group which Van Dyke remembered as “the outcasts, the rebels, the people who didn’t fit in.”

In his career with the Recreation and Parks Department, Kamaka worked at China Beach, Aquatic Park, and Balboa Pool, but his domain was Ocean Beach and Fleishhacker Pool. This kingdom was pulled away when Fleishhacker’s closed in 1971. Cliff retired in 1976 and died less than two years later from stomach cancer at the age of 56.

I don’t want to mythologize Cliff or downplay the important contributions many others made to the Ocean Beach and Kelly’s Cove scene, including younger Hawaiians like Art Octavio and Frankie Freitas, plus transcendent originals such as “Queen of the Beach” Carol Schuldt. But as the seminal bonfire-days generation of Kelly’s Covers pass away, I don’t want Cliff forgotten.

We often honor people for what they do, for action and achievements, but some individuals change the world just by how they live, by how they treat others. Cliff Kamaka certainly accomplished a lot—he literally saved people’s lives—but perhaps his broader contribution to Ocean Beach and surf history is how he engendered joy, understanding, and perspective.

I am generally a loud and persistent opponent to naming things after people, but if anyone deserves some recognition at Ocean Beach it’s Cliff Kamaka. Even a few photos and some text on display in the Beach Chalet lobby would be something, because the wet-suited young men and women who ride Ocean Beach’s cold waves today owe him a debt and they don’t know it.

If Cliff was alive, he’d probably think he was the one who should be offering gratitude.

“I loved this place,” he said at his retirement party. “It was my life. I loved the people, the children, the atmosphere, the work. I was a beach boy from the day I was born, and I couldn’t have imagined a better life than I’ve had here.

“I hope there is a way I can say ‘Aloha’ to all the people I have worked with and for during all these years.”

Great thanks to Mike Phipps for sharing his memories of “Uncle Cliff” and to Anita Kamaka for the family photos.

Give to the Woody Beer and Coffee Fund

Are you thirsty? I'm thirsty. Every dollar donated to the Woody Beer and Coffee Fund is definitely not tax-deductible but does contribute to general conviviality.

Ready to partake with me in coffee and conversation or beer and blather? Let me know when you're free!

Sources

Interview with Michael Phipps, February 10, 2023.

Lorri Ungaretti, Fred Van Dyke, Western Neighborhoods Project website.

“Great Highway: Journey to the Soul of San Francisco Surfing,” documentary directed by Mark Gunson.

Andrew Curtin, “The Monuments to Lifeguard's Career Live On,” San Francisco Examiner, October 26, 1976, pg. 3.