Orphan Asylum

The stone castle which gave shelter to thousands of children and two street names to San Francisco.

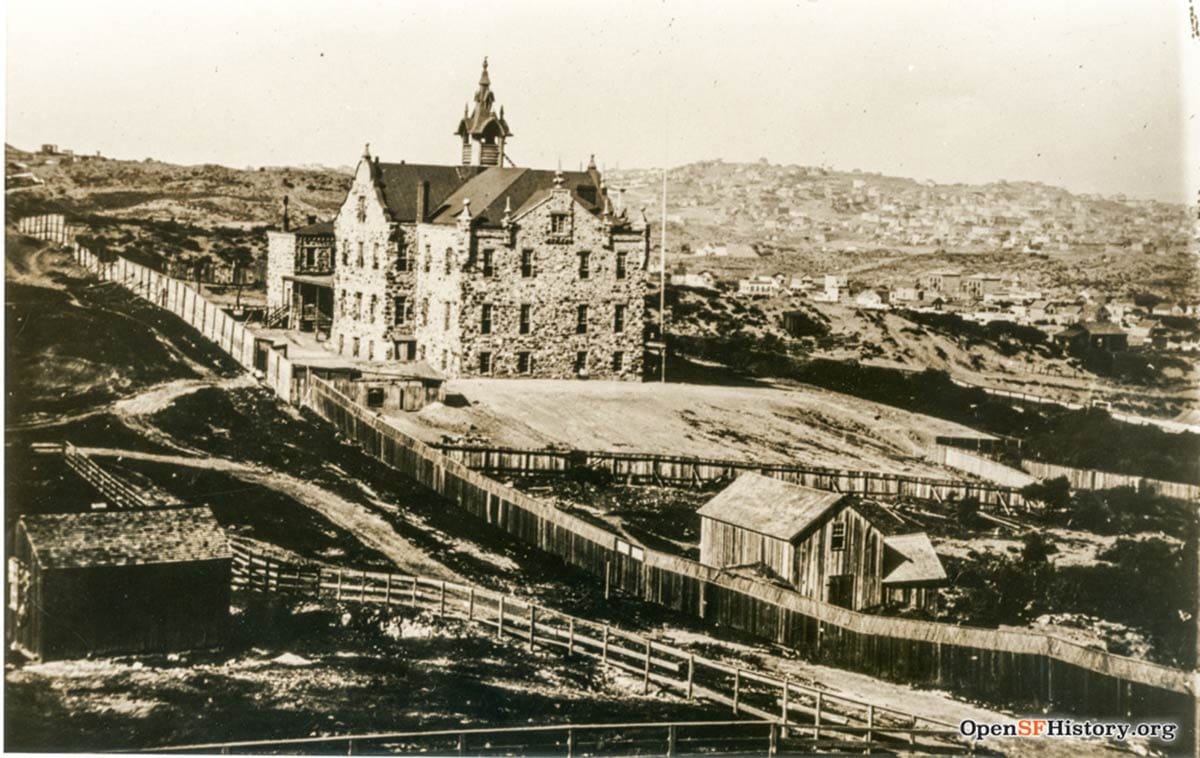

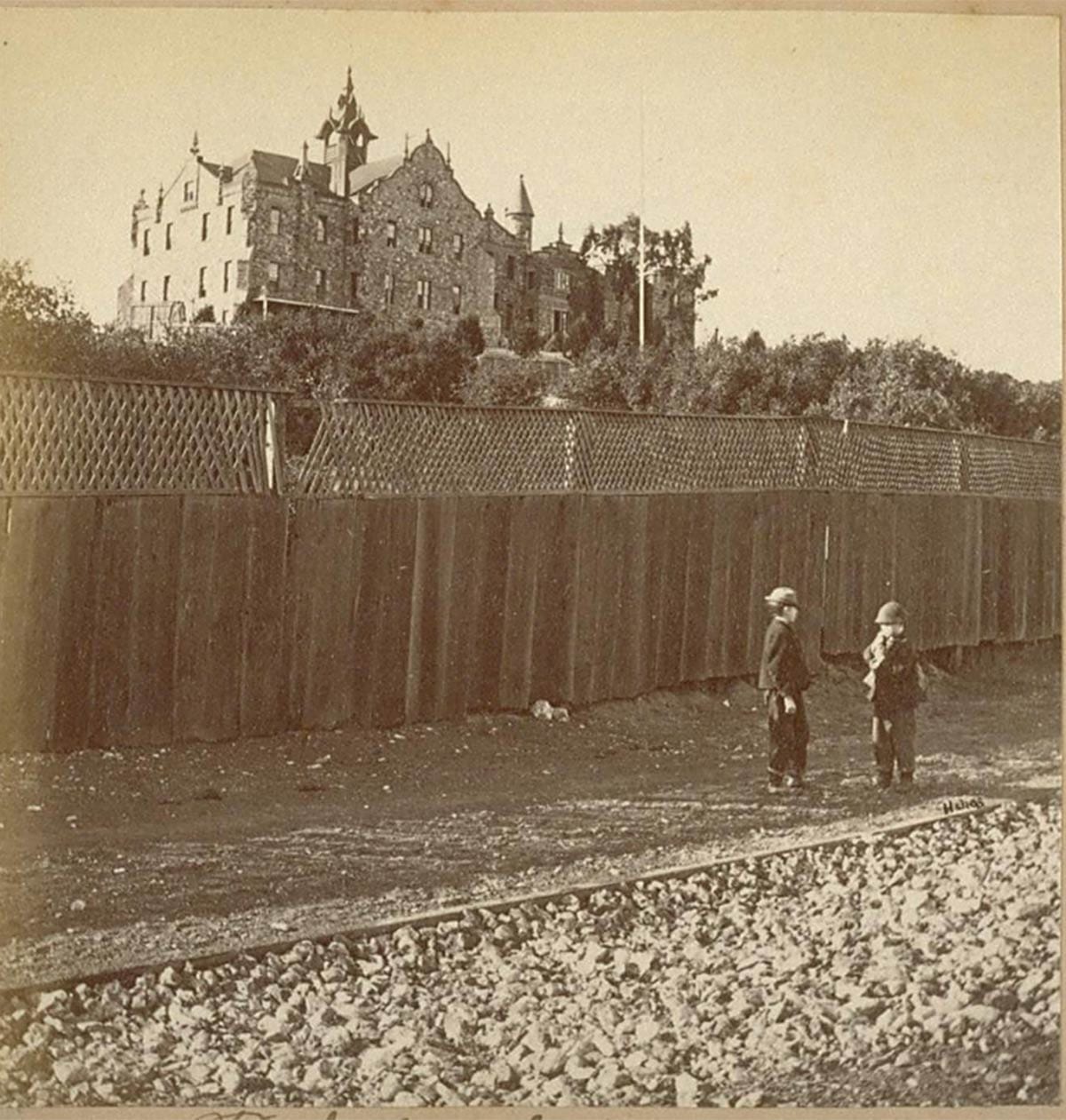

In some early vistas of San Francisco appears a strange castle-like structure on a knoll. Grainy gray photographs do the building no favors. With the surrounding landscape of gnarled scrub and an architectural style giving off “House of Dracula” vibes, you’d be forgiven for thinking this was a place to avoid on a stormy night.

Today, the location of that castle is on the east side of Mint Hill, specifically where a luxury apartment complex “offering unparalleled lifestyle experiences” stands along Buchanan Street between Haight Street and a closed-off block of Waller Street.

Despite its appearances, the old stone edifice—gone now for more than a century—was a place of refuge, a shelter, and a home of care for the youngest and most vulnerable of a new city.

Bring Unto Me the Little Children

Gold Rush-era San Francisco was both an unhealthy place and a city being made up on the fly. In the early 1850s any institution to care for the sick or dependent needed to be invented. Nascent local churches and charities, formed along ethnic and religious lines, did most of this work.

California’s first social service agency was born from an immediate necessity. When the steamship Northerner docked in San Francisco on December 29, 1850 six of its passengers were children whose parents had died of malaria on the trip up from Panama. The new boomtown, less than two years old and barely able to manage itself, suddenly had orphans to shelter.

On January 31, 1851, a group of energetic women led by Elizabeth Waller took on the job. As recorded in the Annals of San Francisco four years later, “a few ladies of the different congregations of the city, cordially met in the First Presbyterian Church, and having buried the hatchet of sectarian jealousies, established the ‘San Francisco Orphan Asylum.’”

At first the budding orphanage had use of a cottage on the corner of Folsom and 2nd Streets. Children received basic necessities and some schooling while the Orphan Asylum Society energetically raised funds on their behalf. Receipts from dedicated concerts, plays, and festivals, along with direct solicitation of donations, built a humble war chest.

By September 1851, the society started searching for a permanent home.

In February 1853, the Orphan Asylum Society acquired two blocks of land beyond the city’s edge on a wild, undeveloped hill. The next month the society took out a want ad in the local newspapers for an architect to plan a fire-proof building of “stone or brick to be erected on the heights.”

G. P. Cummings, and later A. H. Jordan, “architects of taste,” were responsible for the design. By quarrying stone from the side of Mint Hill (as it is known today), the building contractor was able to avoid making a brick kiln.

It’s hard to describe the style of the orphanage, but it was fairly unique for 1850s San Francisco: cupola, parapets, multiple and randomly placed towers and finials, and a cladding of blue-gray stone which seemed to be going for chateau-constructed-of-random rocks.

It has a bit of Heidelberg Castle flair:

In March 1854, the orphanage staff and 23 children moved in to their new orphan asylum. Later, a school building for the education of the younger residents was constructed on the south half of the lot. Made of wood with a pyramidal tower over the entry, it didn’t try to match the main building style, but still somehow gives off some mild horror movie feels today:

Protestant Values

The leadership of the San Francisco Orphan Asylum Society was Protestant—some of the directors were wives of prominent ministers. As Roman Catholic and Jewish communities created their own homes of care, the Orphan Asylum was soon more clearly defined as the San Francisco Protestant Orphan Asylum (SFPOA).

The organization and operation of the Protestant Orphanage reflected the values of the time. The SFPOA founders, board of managers, and staff were all women, as 19th century conventions dictated that child-raising was the job of women. (The organization’s first male board member didn't arrive until 1958.) As researcher Angus Macfarlane wrote:

“Deterred from working by Victorian-era conventions, upper class women often assumed the burden of helping the needy at a time when there were no publicly funded agencies, organizations or institutions. With their abundant energy, free time, intelligence, social contacts and Christian virtues, these wives of well-to-do husbands, through their goodwill organizations known as ‘charities,’ were a lighted candle in the otherwise dark world of society’s unfortunates.”

Women were also considered spiritually purer than men and charged with safeguarding the moral values of their community. (Thanks for keeping us nutty guys in line, women.)

So, in addition to feeding, clothing, and sheltering the orphanage residents, the staff and its guiding board were supposed to instill Protestant ethics and rectitude. In its early years the institution rejected children of parents believed to have led “immoral” lives, no matter how dire the need.

The SFPOA shepherded over 3,500 children in its first fifty years of existence, with the population in the dormitory-style rooms on Haight Street reaching as high as 300 children at a time. The organization placed children in adoptions and gave them training in carpentry and other skills. As wards aged out of the institution some were given seed money to embark on trades such as dressmaking.

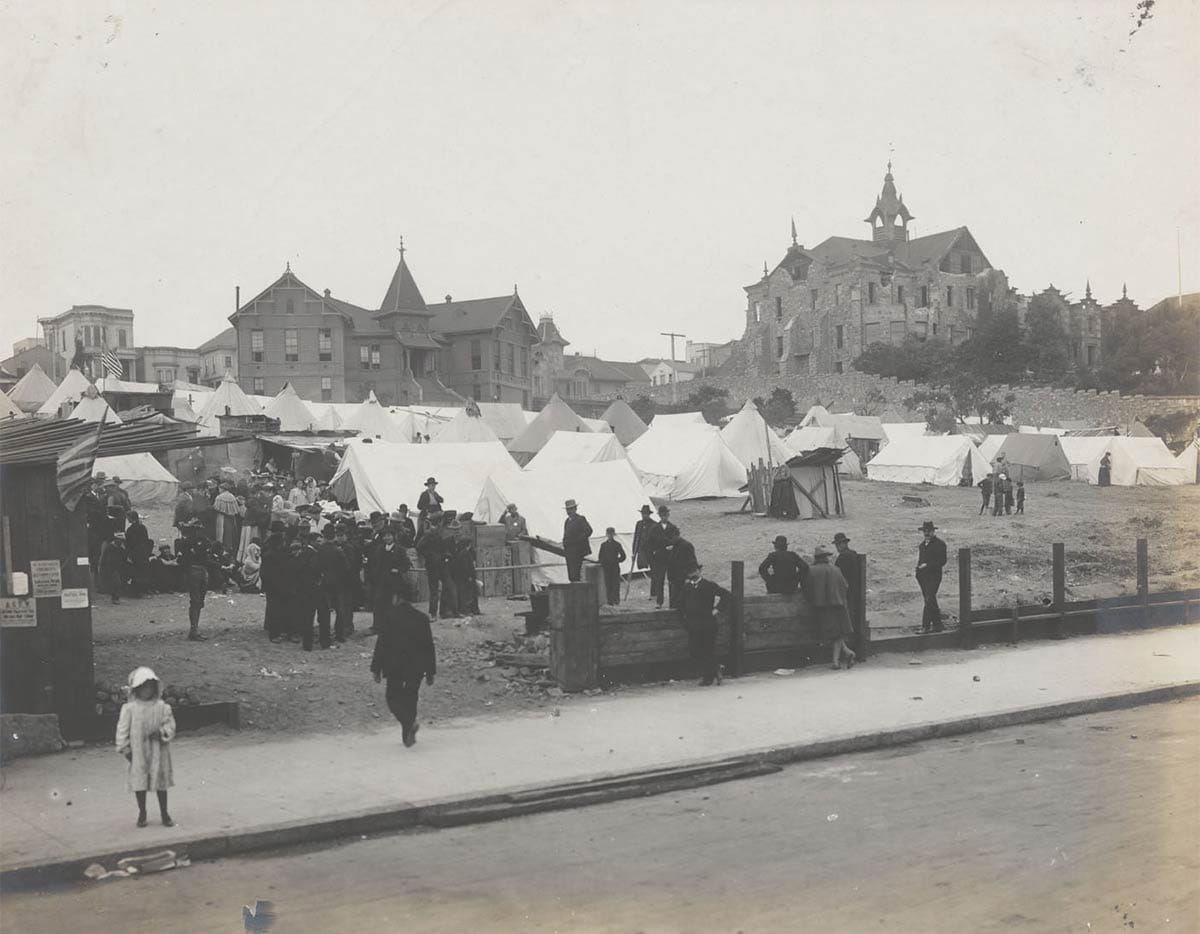

The SFPOA survived the great April 18, 1906 earthquake, but the condition of the aging structure and the changing model of care for children inspired a relocation plan a few years later.

In the 1920s, the Haight Street campus was sold to the State of California, which had been leasing part of the property for a teacher's college since 1905. In 1923, the Protestant Orphanage bought ten acres of land along Vicente Street between 28th and 30th Avenue in the Parkside District for a new campus, Edgewood.

Models of care have evolved from the orphanage days, but Edgewood Center for Children and Families is still there, today a multi-service agency for some of the most at-risk children and families in the Bay Area.

The kids who come to Edgewood are trying to overcome abuse, neglect and mental illness and are given help in the form of behavioral health programs, family support, and educational services.

One More Legacy

One of the best stories about the old orphanage? When the city’s Van Ness Ordinance adopted a re-survey of the Western Addition in 1856, two of the streets bordering the orphanage were named to honor instrumental leaders of the San Francisco Protestant Orphan Asylum Society, Weltha Haight and Elizabeth Waller.

Researcher Angus Macfarlane has nailed down and laid out the Haight/Waller naming story (and much more), which you can read on FoundSF. (If you are in a hurry, this chapter has the specific street-designation details.)

Cool, right? How many other San Francisco streets honoring women can you name?

Woody Beer and Coffee Fund

Hurray for Diane M. (F.O.W.) and David F. (F.O.W.), who made sure the Woody-buys-someone a-beverage bank was solvent. The masses rejoice.

When and where can I purchase you a coffee or beer?

Sources

Frank Soulé, John H. Gihon, M.D., and James Nisbet, The Annals of San Francisco (San Francisco: D. Appleton & Co., 1855), pg. 716.

“Protestant Orphan Asylum Celebrates an Anniversary,” San Francisco Chronicle, April 12, 1901, pg. 7.

Angus Macfarlane, Naming of Haight Street, FoundSF.org website.