San Francisco Story Annual 2023

(This is 60 printed pages in one website scroll, which may be your thing. You can also download a version in PDF and ePUB formats or pay for a printed copy.)

Welcome to the second San Francisco Story Annual. Last year I created a little book like some indie literary journal you might subscribe to or pick up at City Lights Books so as to feel artsy and bohemian and a wee pretentious. (No judgment: that’s me all over.) Inside, there were two articles, much longer than I could do for my weekly San Francisco Story emails.

I was all ready to do something similar this year, the plan being to make one annually until I’m 70 years old. I figured you could all have a nice matching set of 14 journals on your bookshelves and feel artsy and bohemian and a wee pretentious.

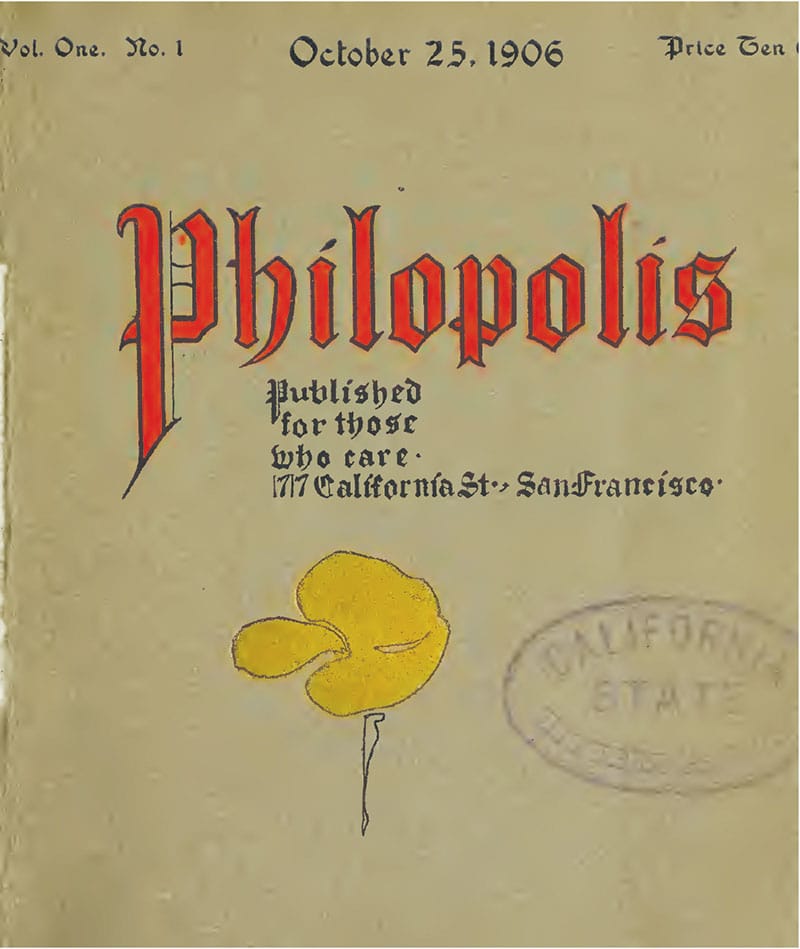

But then, researching something else online, I stumbled upon a scanned collection—one big PDF—of an old periodical called Philopolis, which began publishing in San Francisco just after the 1906 earthquake and fire. The title page of each issue had a paragraph reading “It is the purpose of Philopolis to consider the ethical and artistic aspects of the rebuilding of San Francisco. We want good art, good architecture, and, as a necessity to gain the end, a good civic administration. This is important. As the name implies, Philopolis is a Friend of the City.”

I definitely consider myself a Friend of the City. I like good art and good architecture and a good civic administration sounds pretty sweet. I also like the Art Nouveau design of Philopolis. So, I thought I’d mimic the cover in the spirit of recovery. Yes, 2023 isn’t 1906, but it was a hard one for me and difficult for the city too. We could use some rebuilding.

We didn’t have another big earthquake and fire destroying the core of the city (although we may soon), but the pandemic did a number on all of us and we’re still trying to regain a sense of ourselves.

I have lost relatives and friends this year. As I’m writing this, shockingly, one died just yesterday.

The Death of San Francisco is a top-five go-to story for our local outlets and the New York Times. All chase clicks with headlines on stolen backpacks, burgled jewelry stores, sad homeless encampments, and closed hipster restaurants. What did some tourist from Korea say? How many fentanyl deaths this month? How much poop can we count on one city block? The daily drubbing of the former “City That Knows How” got so stale that now we get the backlash articles: “‘Not-a-hellscape,’ claims local man.” It turns out if you lift your head from the poopy sidewalks (but still, watch your step), this is a beautiful place where kids go to school, musicians jam in cafes, lovers kiss on corners, and the raking winter light on the bay and the bridges can choke you up.

We’re not the “knows-how” city President Taft called us in 1910, but haven’t been for a long time. In the second half of the 20th century, we were the home you didn’t have at home, where to find your people; the city of the good idea; at times, the nation’s conscience, the irritating member of the family that was right, but did they have to be so smug about it? And we were the pretty one, which could really get people’s goat.

The powerful and the want-to-be powerful, the venturing capitalists, the tower builders, the hoodied young techsters, and the bicycling millionaires put us into hubris red zone. We were coastal elites: dishwashers, social workers, and baristas somehow lumped with start-uppers, NFT-hucksters, and political climbers. We primed ourselves for comeuppance. Neighborhoods became stage sets and morality plays and somehow getting focaccia at Victoria bakery at Washington Square meant something. Am I playing the role of a San Franciscan? Am I one?

Don’t overthink it, man. Breathe that air, walk in the park, and listen to your nephew at open mic night at Simple Pleasures.

Don’t worry, Friends of Woody. There’s not 60 pages of metropolitan existentialism. Philopolis inspired me to end 2023 with a feeling of rebuilding and an optimism for a new year. Inside you will find 23 mini-tales too short for my weekly post: image, text, image, text. Some are about Woody family, some are not, some a bit nostalgic, but everything is San Francisco in some way.

To my old friend, Arnold Woods: I hope in heaven every concert is by rock legends, that the Mets and Giants alternate winning the World Series each year, that you find a great pickleball partner until your friends here can join you, and that the refrigerators are full of Coke Zeros.

Thanks for all you’ve done for us. You were always the one to count on and it’s hard to know what we do now.

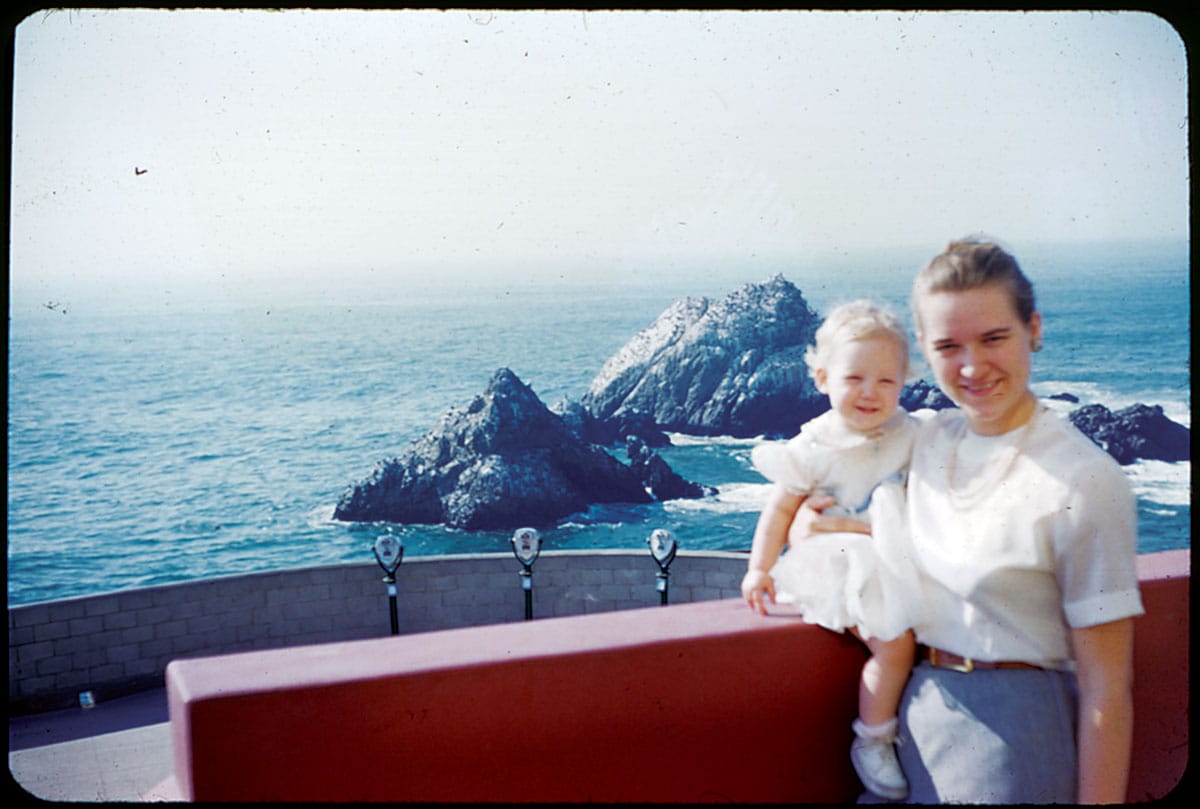

Donna, Diane, Seal Rocks

My mother-in-law, Donna Rice Myrick Payne, died this year on July 16, 2023. She passed away peacefully in her bedroom downstairs. (We have a classic San Francisco arrangement: different generations living in different flats in one building.) Donna’s obituary detailed her very full life and accomplishments, but it really could have been one line: “She was one of the nicest people anyone could meet.”

Born in West Virginia, Donna drove across the country in a trailer with her first husband, Randy Myrick. They settled in Napa, California, and both worked for the school district for decades. Their first child, my sister-in-law, Diane Myrick, learned to walk in that trailer crossing the continent. In this slide photo from 1960 at Seal Rocks, behind the Cliff House, Diane looks a lot like my daughter Miranda.

Donna volunteered for everything. She’d be the first to raise her hand. She was the one bringing the deviled eggs. You could not slow her down. She raised three children, held down a job, and got her college degree through a correspondence program at the University of San Francisco. (“It was online before there was an online,” she’d say.) She outlived two husbands she loved deeply, backpacked in Europe with Nancy, and was ridiculously proud to discover she was President Barack Obama’s fifth cousin once removed. ◊

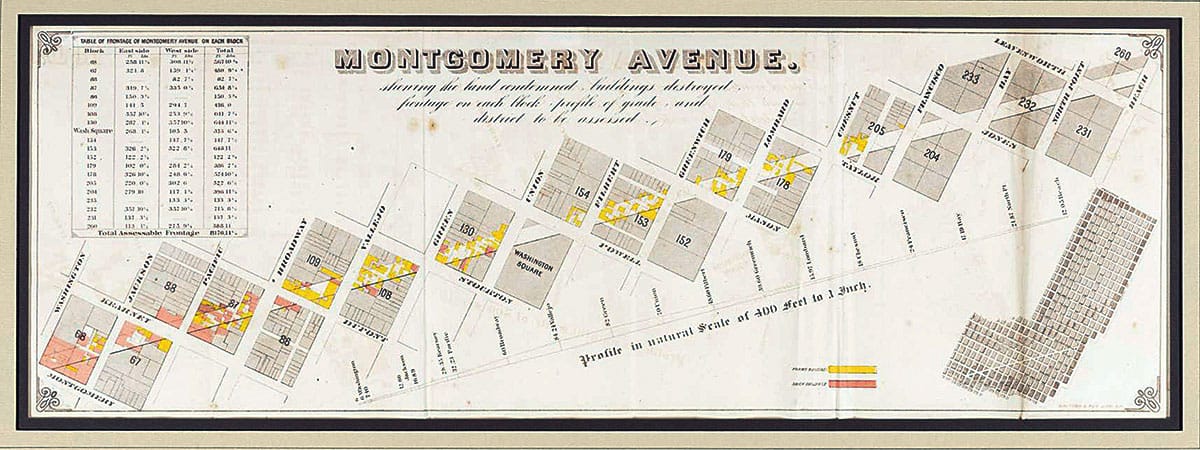

Making Columbus Avenue

This little map explains why Washington Square in North Beach isn’t a square. (What it doesn’t do, alas, is explain why the statue in the middle of Washington Square honors not the first president, but Benjamin Franklin. That’s another story.)

Maps make order of our world. They attempt to describe reality or reshape it. In 1847, Jasper O’Farrell gave San Francisco (then Yerba Buena) a plan of blocks and lots made up of two angling grids glued together at a bisecting Market Street.

Two decades later, when the northern waterfront became a center of commerce, the wiggling jogs of O’Farrell’s map frustrated the swift conveyance of goods to and from downtown. So, in 1870, a new map and new diagonal came to the rescue with an extension of Montgomery Street to the water.

Sure, buildings needed to be razed (wood-frame is represented by yellow, brick by red), but scraping an arrow-straight line north represented Progress with a capital P. The San Francisco Examiner predicted other blessings of a wide new road: “Light, fresh air, a thronged avenue, and the police, would in a short time drive from their haunts of sin and crime the degraded creatures who now infest a portion of the city worthy of nobler uses.”

Oops, it clipped off a corner of Washington Square. No one minded much, since the park then was little more than dirt fenced off from dairy cows and dogs. In 1909, the Montgomery Avenue was renamed Columbus Avenue and a disconnected triangle of park remains stranded on the west side of the street. ◊

John Neate 1850

My great-great-great grandfather, John Neate, came to San Francisco in 1850. He sailed on the barque Lydia, entering the Golden Gate on July 9, 1850, exactly 6 months after his ship departed Liverpool, England. I have no photos of him before he was an old man, but this small, round, wooden box, about 2 1/2 inches in diameter, has been passed down through the family. The circle of ivory at its center reads “J. Neate 1850,” and I assume it was a present or a memento he had made to commemorate his voyage around the world.

A snuff box, maybe? My mother’s cousin, Bob Cangelosi, lived for many years in the house purchased by his grandmother, Iris Neate Markstrom Shook in the 1920s. (Two husbands made for that long name, but we simply called her “Auntie I.”) Little treasures tended to turn up in drawers and closets. Bob let me photograph the box years ago, but I don’t know where it is now.

Neate established a cement factory, discovered quicksilver on a hill in Solano County, established mining claims throughout California, and abandoned his wife to return to England. There he bigamously married a young woman and had three children with her. He eventually came back alone to San Francisco, just in time to survive the 1906 earthquake and fire. In the 1910s, he self-published a booklet of poetry and died at 1684 Fulton Street, 92 years old, in 1919. ◊

Seal Rock Hotel

Despite what my imagination may hope for, a visit to the Seal Rock Hotel would probably disappoint. The first known structure at Ocean Beach, constructed in the 1850s before any real road had been sliced through the western sand dunes, its apex of class and sophistication likely is shown in this early 1900s photograph.

Perpetually run down, the Seal Rock House’s renovation into the Seal Rock Hotel coincided with an early 20th century eruption of beachside attractions a block away. These later evolved into the amusement zone “Playland at the Beach.”

Seal Rock wasn’t a hotel for the family, but temporary workers, bartenders, men who were passing through or found themselves stranded after a night of drinking. The most illustrious guest was likely the boxer Jack Johnson, who trained next door at the Ocean Beach Pavilion in 1910.

The interior was likely dark, smoky, a place you might want to keep your guard up. The glassed-in porch probably offered the best experience, but the view of the ocean and passing vehicles wouldn’t have been much better than what you get today having waffles at the Beach Chalet. The real attraction would be the era, seeing San Franciscans in another evolutionary state: their clothes, the way they walked, the way they looked at you, the words they used, their cadence.

The Seal Rock building was demolished in 1972 and the land below Sutro Heights is now the unromantically named Parcel 4 Open Space. ◊

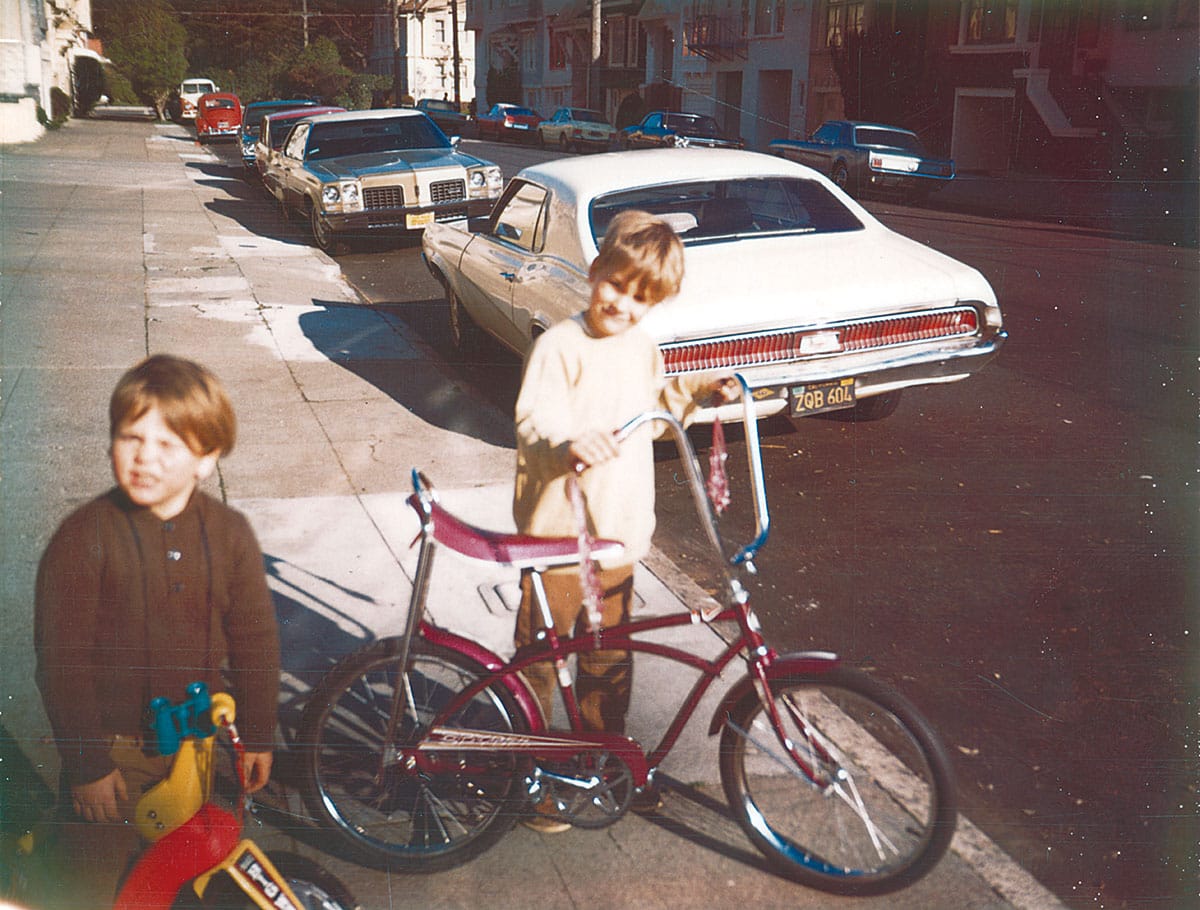

11th Avenue Christmas

My father put an 8-track tape player in our 1969 Mercury Cougar. The bulky contraption sat on the hump between the front seats and one had to really lean on the wide plastic cassettes to get that satisfying clunk and hear Three Dog Night. We lived in a basement apartment at 139 11th Avenue. We didn’t have a garage and didn’t need one. There’s the car parked in front with another space behind it. We just had the Cougar, and despite being a sporty muscle car, we were all able to fit in it with a lot of camping equipment to go to Yosemite.

Check out the mylar purple tassels on my handlebar grips and the banana seat on the new Christmas-morning ride… My brother Matt got a Big Wheel and some plastic binoculars. As is usual in his childhood photos he doesn’t look happy about it. The younger brother always sees the inequities.

The day our mother was to return from Children’s Hospital with our new brother, Christopher, we set neighborhood scouts at each end of 11th Avenue. My cousins and the McEacherns, the Flynns, Gabriel Gonzalez, even some of the Jues, played along with us. Straddling bikes, we stood sentinel to spot the car, ready to pedal back mid-block as Paul Reveres announcing the arrival. ◊

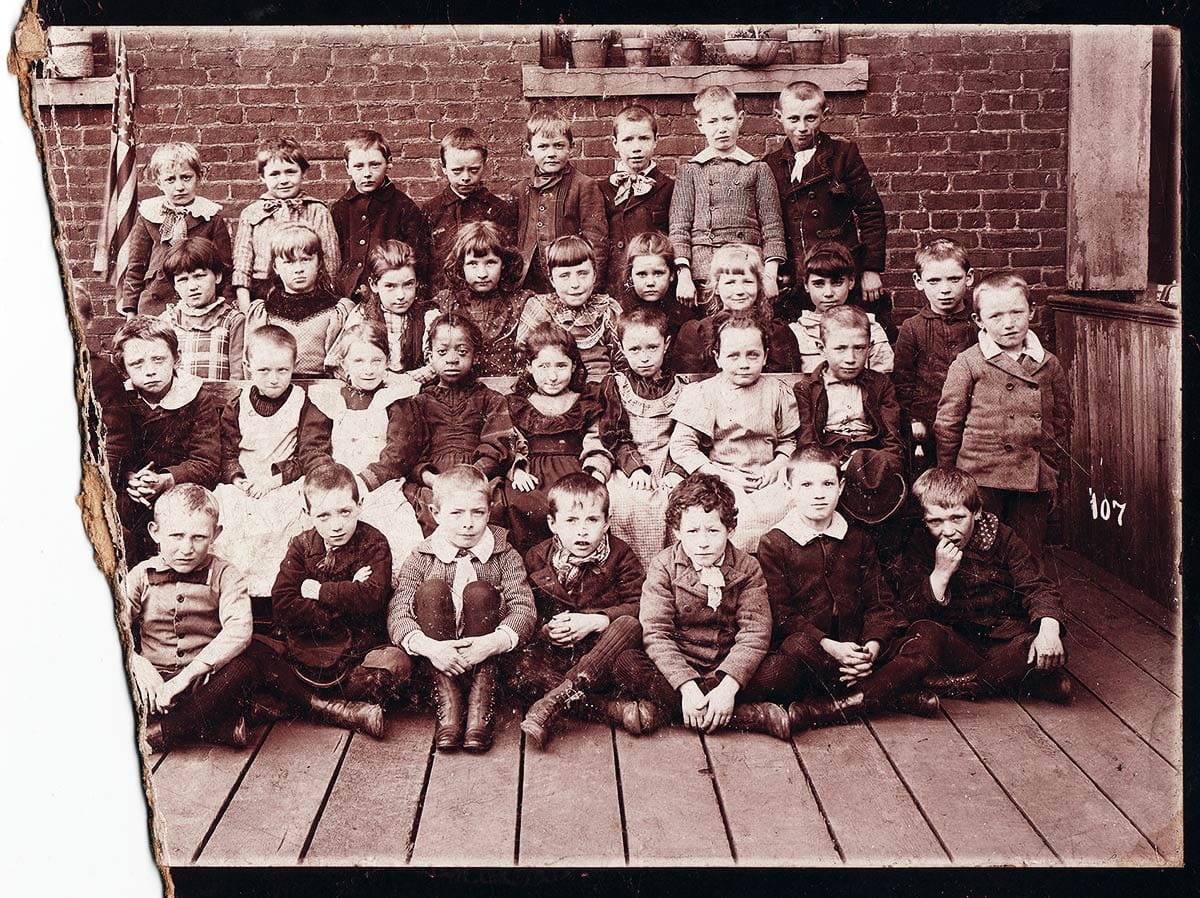

South of Market School Days

My great-grandmother Ethel Neate (later Slinkey) wears a polka dot dress and sits right behind the one African American girl in her class at Jefferson School in the 1890s. Five hundred and fifty South of Market kids filled a brick building which stood on Tehama Street between First and Second Streets. It was a rough neighborhood before the 1906 earthquake and fire. Some of the faces of these children tell that story.

In 1896, the San Francisco Call complimented Jefferson School for improving its reputation: “The children don’t fight as they used to; they don’t stone cats, or tie cans to the tails of dogs or molest the sons of the Flowery Kingdom [Chinese men].” Previously, “the urchins of Jefferson School had daily set-tos in back lots, and skinned faces, black eyes and broken noses, as well as bruised hands and lame legs, were not rare things.”

The Neates likely lived on two-block-long Hawthorne Street when this photograph was taken. Ethel’s father worked as a teamster for nearby Whittier, Fuller & Co. on Fremont Street off Howard Street. The family moved almost yearly and by the time of the 1906 earthquake, when Ethel was 19 years old, the Neates—parents, three boys, two girls, and a couple of boarders—were all crowded into one flat at 1755 Howard Street. Almost all they had was lost to the fires. ◊

Excelsior Playground

Excelsior Playground occupies half of a block of the world. Russia Avenue runs across in the background, Madrid Street is on the right, and that dirt path up the hill at left is Edinburgh Street. On July 30, 1912, the girls in homemade and overall-clad boys sprint on a patch of dirt little different or distinguishable from the surroundings, but dedicated to their enjoyment.

Playgrounds were a 20th century invention. The idea of childhood, a time of life in which expectations and experiences could and should be different from the adult world, was a new concept.

In San Francisco, in my lifetime, grown-ups have stolen the playgrounds. When I was a kid in the early 1970s, most adults didn’t exercise. Of those who did, few were women. Jogging was new, a craze, a fad. Surfers were outcasts. Men who played in softball or baseball leagues socialized and drank beer between pitches more than they ran. Wealthy people blessed with leisure time and the dues for private clubs played golf and tennis. We kids bristled when adults began invading the tennis courts of Mountain Lake Park on weekend mornings. Play was for children.

Now we live in a Nike world. Softball fields and pickleball courts and gyms are reserved spaces. Teens are pushed to the edges of pick-up basketball games. Some children only visit playgrounds as toddlers brought to a sand box or as guests at a classmate’s birthday party.

Rise up, children, like these rag-tag, dust-covered ghosts of the past, and reclaim your inheritance of gopher-holed, clover-filled fields. ◊

Team Captain

In a late July game in 1921, my great-granduncle Arthur Neate took a pitch in the face, breaking his nose. He stands next to the man in the cardigan, arms crossed, looking every bit like the captain of the Schussler Brothers company team, which he was. The nose doesn’t look so bad, so the photograph probably predates the fastball to the schnozzle. I haven’t yet figured out the location, but that water tower behind the telephone pole makes me think somewhere in the southeastern part of the city.

Arthur was a gilder for a company which made and sold “mirrors, pictures, frames, glass, picture moldings, theatrical display stands, window display fixtures, artists supplies.” The factory and wholesale warehouse was at 326–338 Grove Street in Hayes Valley and the retail store was downtown at 285 Geary Street. The 1920s were the era of movie palaces and new apartment buildings with murals, mosaics, and gilt pier mirrors in the lobbies. Schussler Brothers met that demand.

Arthur and his brother Albert married twin sisters, Ella and Ethel Knapp. They were introduced by one of the Neate sisters at the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition. (That’s the fair that gave us the Palace of Fine Arts in today’s Marina District.)

While still recovering from the broken nose, Arthur became a father. His wife, Ethel May Knapp, bore twin girls on August 25, 1921. The babies only lived a couple of weeks, perhaps born premature, and the couple never had any other children. ◊

India Basin, 1944

How many history items can you pack in one photograph? At least five. This is India Basin at Hunters Point on November 7, 1944, a shot taken from a ship’s mast. Walter Anderson and Alfred Cristofani began building scow schooners on this site in the early 1870s. The Albion Brewery, with its own natural spring to tap, opened about the same time. Its “castle” building surrounded by scaffolding in the photo is still at 881 Innes Avenue. (1)

Just to the right of the road up from the yard, you can see the white back of an 1875 house with a center chimney rising above its gable. (2) That humble shipwright’s cottage at 900 Innes Avenue is designated as San Francisco City Landmark #250 and is under restoration as the centerpiece of a new public park.

Another old house, 911 Innes Avenue, is visible across the street just right of the tree. (3) It looks better in 2023 than it did in the 1940s and today always has a rocking chair on its front porch. Snaking along the hillside are recently constructed buildings of “Harbor Slope,” an early San Francisco Housing Authority project subsidized by the U.S. Navy for arriving war workers. (4)

All of that and I haven’t even talked about the watercraft. On the left edge is the USS Arivaca, built by the Anderson & Cristofani company and launched just a week before the photograph was taken. (5)

Can we all take a moment to romanticize the days of blue-collar jobs and skilled craftwork in the city? We’ll skip the wars and the toxic chemicals and the back-breaking for just one second. We desk-dwellers need our Arcadian fantasies. ◊

Sears, 1956

Some of my earliest memories are about shopping, the mark of an American childhood. Sears at the top of Geary Boulevard was where my brothers and I were taken for shoes. Murals depicting California history, at least a version of it, distracted me while suited men knelt and laced up possibilities on my feet. Those scenes of friars, conquistadors, and gold-rushers combined with “Meet the Presidents” Step-Up books to spark my nascent interest in the past. For a while after Sears closed in the 1990s, I was on a hunt for those mural panels, wondering if they survived behind the drop ceilings of the Mervyn’s and other successor stores. They’re gone. Target is here.

The Sears sign with that skinny S acted as a landmark visible from most of the Richmond District. That was the border of my world. Beyond it was the land of adult occupations, where my grandmother worked at Kaiser Hospital, and where journeyed the businessmen who knew how to fold morning newspapers best for reading on the bus.

The streetcars ended before I was born. (That’s a C-line car, headed to its terminus at 2nd Avenue and Cornwall Street.) The Geary Expressway tunnel was dug under Masonic Avenue before I was born. The Sears was constructed on the grounds of the evicted Roman Catholic Calvary Cemetery before I was born. Now, I write about things that existed before many of you were born, like when salesmen knelt to tie your shoes and pressed down to find your toes. ◊

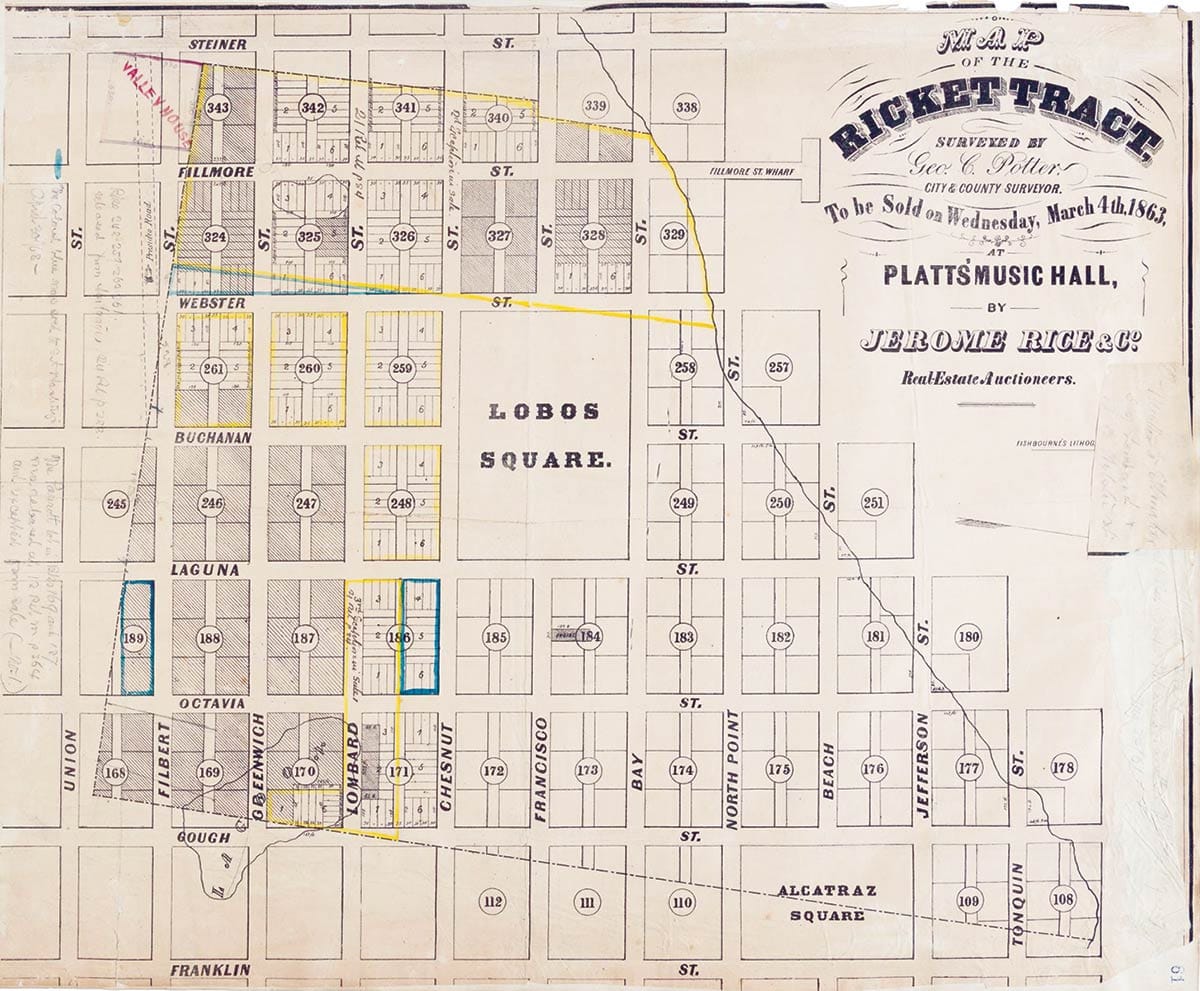

The Marina District, 1863

Live in the Marina District for cheap atop a muddy lagoon. In 1863, it was possible. This is a promotional map for an auction of lots around what was then demarcated as Lobos Square and today is Moscone Playground with the same footprint. “Alcatraz Square” at bottom was never a thing beyond maps, an imaginary non-square-square now in the middle of Fort Mason.

The land for Fort Mason, owned by John C. Fremont, was seized by President Abraham Lincoln the same year as this map. The Civil War raged. Serious worries about Confederate raiders pushed the United States to bolster its coastal defenses. Lincoln and Fremont didn’t get along. Fremont’s heirs fought for compensation until 1968.

Despite the map’s neat blocks and straight lines, this was a muddy tidal land and home of a few dairy cows, some squatting crabbers, and laundry works. The home lots optimistically drawn at the corner of Lombard and Gough Street lie within a body of water known as “Washerwoman’s Lagoon.”

Why are three sides of the Ricket Tract at an angle and cutting some of the lots into inconvenient slivers? Until the mid 1850s, the city’s western boundary was Larkin Street. A development scheme around the lagoon, then in the wilderness, was surveyed without regard for the city grid. Awkward land claims resulted when San Francisco extended west. I love old maps for the stories, the lies, and the often-naive hopefulness they convey. ◊

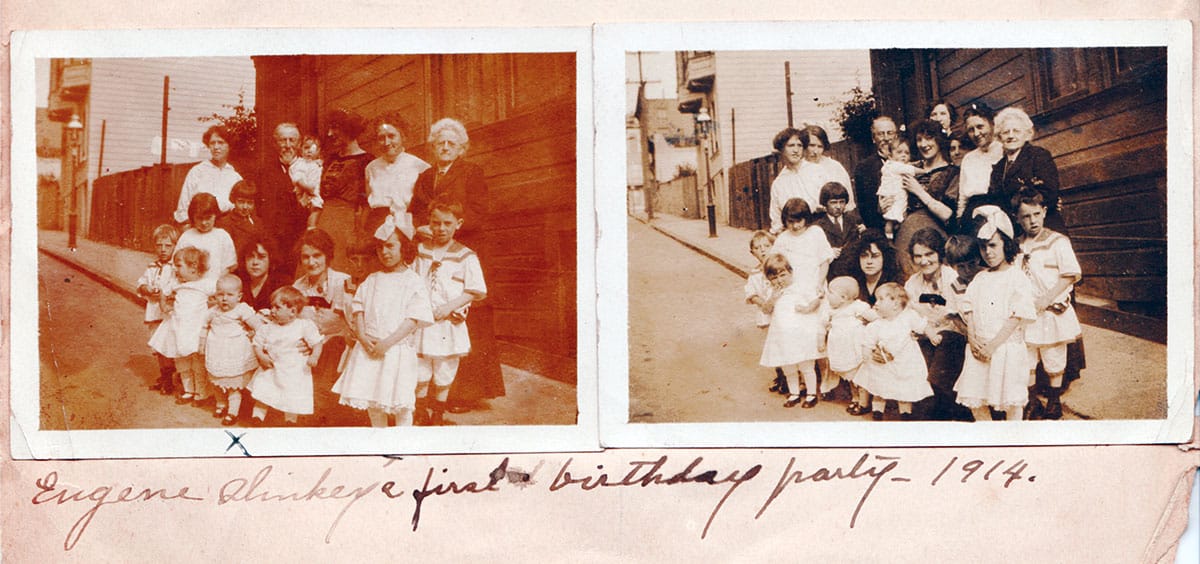

First Birthday

After more than five years of trying, multiple miscarriages, and despair, my great-grandparents succeeded. They had met in a refugee camp after the 1906 earthquake and fire, each having lost most everything but their youth. They married in November 1906, and in July 1913, finally, Milton and Ethel (Neate) Slinkey had their baby.

After living in crowded flats with parents, brothers, and roomers all together, the couple found their own place at 238 Myrtle Street, an alley mid-block between Van Ness Avenue, Franklin Street, Geary Street, and O’Farrell Street, and that’s where Eugene Slinkey arrived in this world. The building somehow has survived and in 2023 looks pretty good in the shadow of condos and retirement-home towers.

Here’s the family and some friends gathered for my grandfather’s first birthday in 1914. The dark building at right holds 238 Myrtle Street. Eugene is the fat bald-headed baby standing at front with an X under him in the left side photo. The goateed man is his great-grandfather, John Neate, the gold-rusher of the snuff box. “Auntie I” stands holding a baby and peeking over her head in the right photo is Eugene’s mother, my great-grandmother, Ethel. ◊

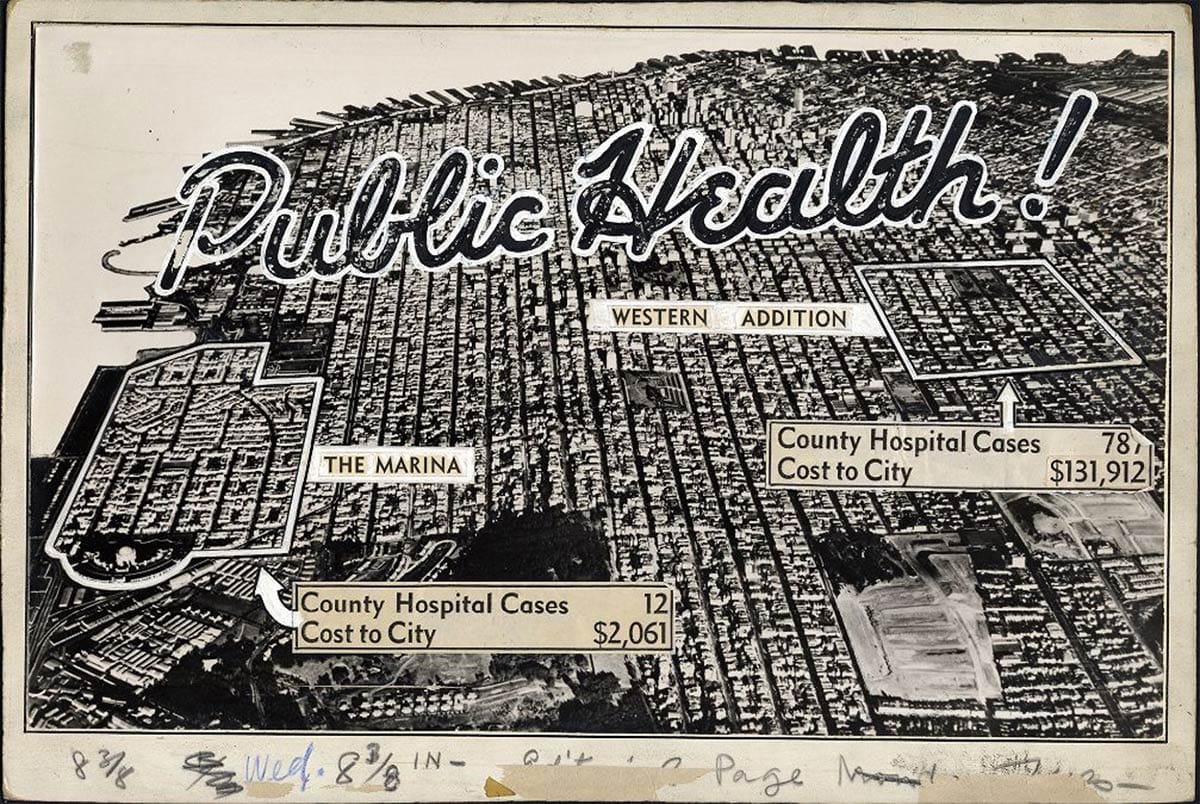

Slum Clearance 1947

How do you keep economic engines turning without a great war? By no means did government contracts for building battleships, bombers, tanks, army posts, navy bases, and war housing dry up when World War II ended. Massive federally funded projects kept big corporations, the states, and cities like San Francisco alive during the Great Depression and made them prosperous during the War to End All Wars (II). No one wanted the taps turned off. “We need jobs for all those returning G.I.s., you know.” Time for freeway-making to new suburban Edens and “urban renewal” of our cities and keeping the metaphorical foot on the gas.

So, we invent “redevelopment,” tearing down a neighborhood to rebuild from scratch, which we can only inflict on the less powerful, the poor and the not-white. And we blame them for the attendant hardships of being poor and not white in America. You can only afford to double up in a room in a crowded flat in a run-down Victorian, which your landlord allows to crumble and decay? And when flu season hits, you all get it? And when you have to go to the doctor you can’t pay to go to the fancy hospital, but have to go to San Francisco General?

Urban blight! We can fix by demolishing your homes and businesses and erecting new concrete towers. It’s all about Public Health, you know. Sure, you can move back in when we’re done in a few years. But we kinda hope you’ll find other accommodations. Somewhere else. ◊

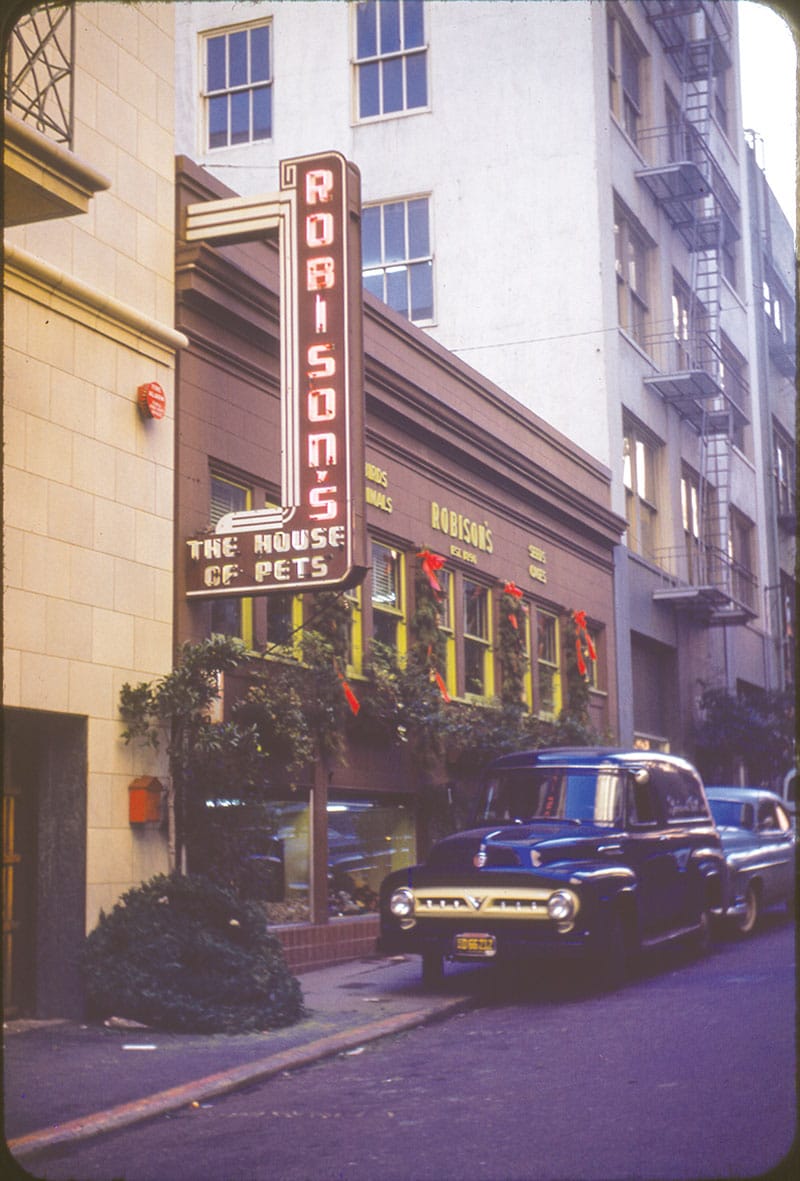

The House of Pets

Summer 1984. After one year, UC Berkeley “de-admitted” me for academic ineptitude. My girlfriend took off for her home in Southern California when the semester ended, not saying goodbye, not leaving her phone number. I was sleeping on my grandmother’s couch. I begged for a job at the Waldenbooks at 129 Geary Street next to Neiman Marcus and began working for $3.35 an hour as a “greeter,” standing at the front door for eight hours, my presence a cheap security measure against a stack of art books walking away. The smell of roasted nuts from Morrow’s Nut House next door nauseated me after two days. Always watching, observing, ever alert at that doorway, I learned the personality quirks of specific pigeons.

In my half-hour lunch break I circled Union Square, gave tourists directions, listened to the busking opera singer, but never gave him any money. He knew I didn’t have it, me eating my homemade turkey sandwich on the hoof.

In Maiden Lane, the little alley between Geary and Post, there was a pet store. I did run-throughs while the sandwiches digested, because emporiums of fancy purses, perfumes, and shoes weren’t me. The house of pets was a house of cages, but also a house of life.

In the spring of 1985, with Marty Molluskhead, I was able to rent the apartment next door to my grandmother. I borrowed a book on parakeets, convincing myself, and the bird and I rode a packed 38 Geary bus home. ◊

Street Cameraman

Joseph Selle standing in Maiden Lane waiting for his next victims. His red uniform cap with badge gives him an air of authority, although the gold lettering on it, “Fox Movie Flash,” doesn’t explain what his responsibilities encompass. For decades, Selle waited on blocks around Union Square and Market Street to photograph men, women, and children.

You’re on a date, maybe a first date. Or just exited a movie with an old friend. Or taking your grandchild to buy new shoes. Walking down the street, mid-step, maybe mid-conversation, you’re surprised when what looks to be a hotel doorman points an odd camera at you. You’re given a numbered ticket and for a fee and your address, told a souvenir photograph of this magic moment can be mailed to your home to remember forever. It’s a good racket and Selle did it from the 1930s to the 1970s.

His custom camera used 35mm movie film, which is why prints look as if they were snipped out of a Film Noir thriller. Each roll had 1,000 exposures. Some thousand of these rolls were donated to the Rochester Visual Studies Workshop after Selle’s death: 1 million images of San Franciscans caught mid-stride.

They are not art. They are more engrossing, fascinating, and emotional than most art. If you had family here in the city in the mid 20th century there is likely at least one of Selle’s snaps in your archive. Grainy, blurry, maybe with a number on the side, here is a second of time travel and your ancestor in hat, gloves, or baggy suit looking surprised to see you blink in and out. ◊

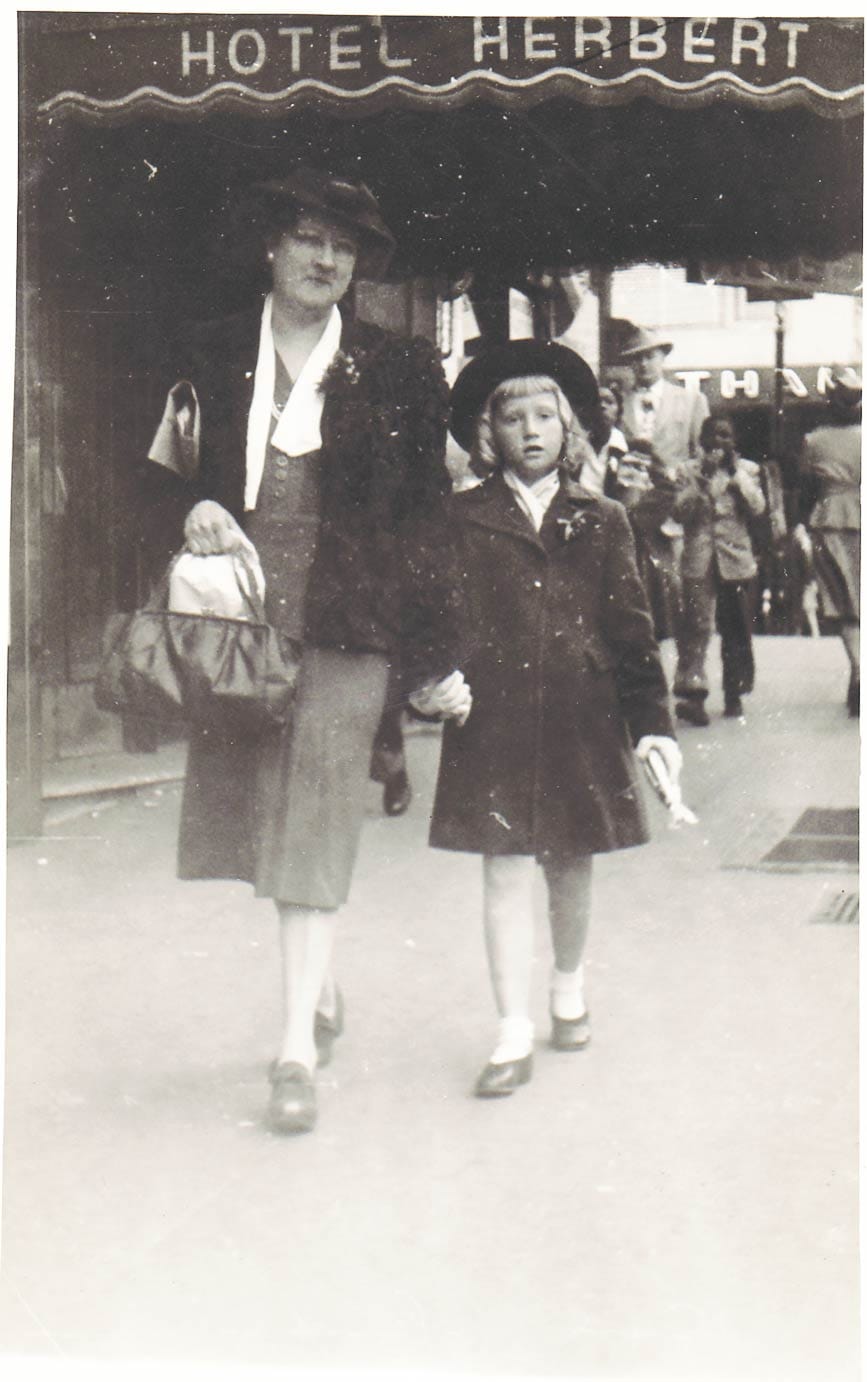

Ethel and Carol

Ethel Neate Slinkey and her first grandchild, Carol Slinkey, are caught by photographer Joseph Selle headed down Powell Street just past O’Farrell Street. My great-grandmother, clutching what may be a bag of candy with her purse, is skeptical. My aunt, holding what looks like a toy rocket, is confused. Dressed well, as people were expected to do then to go downtown, they each have a small spray corsage pinned to their lapel, perhaps Christmas related.

The Hotel Herbert is still at 181 Powell Street. The entrance no longer has a canopy, but a vertical sign continues to hangs above the cable cars and the tourists. Once flashy bright neon, it now reads “Herbert” in a dull modern font. ◊

Magic Carpet, 1963

Elevated freeways thrilled me. Whenever we returned from some exotic adventure in the east (say, Oakland, where my father co-produced the California State Karate Championships), we magic-carpeted among landmarks in the city’s skyline. After the Union 76 sign, set on a triangular obelisk just off the Bay Bridge, the Planters’ Mr. Peanut neon, then swooping within what felt like arm’s reach of the Baha’i temple’s cornice and the First Baptist Church’s gold dome. Past City Hall we’d make a dipping descent and a hard left—boom—onto Fell Street heading west, down among the mortals once more.

When my father wanted to give us a treat, especially at night, he would detour onto the Embarcadero Freeway to glide past the Ferry Building’s tower and land on Broadway so my brother and I could see Carol Doda’s neon nipples and Big Al holding his machine gun. Then the Broadway tunnel—tunnels were always special.

Some people protested the demolition of the Central and Embarcadero Freeways after the 1989 earthquake, mostly merchants in Chinatown and westsiders upset at losing their expressway to home. But the eradication of those view-blocking concrete snakes is now universally considered a good thing. (Even if that Fell/Oak/Octavia junction we now navigate is always problematic.)

I agree. Good thing. And also wish I could fly along the Embarcadero one more time. ◊

16th and Market

Love that mustard-painted Donahue pharmacy building on the corner of 16th, Noe, and Market Streets. Whenever I see such colors I long for what we miss in millions of black-and-white photos. Today, that corner is home of the Lookout bar with its wrap-around second story balcony full of shirtless men on warm days.

I also love the homemade mortar-and-pestle sign propped up on top of the garages.

No trees obscure Corona Heights, a rocky prominence quarried into the 20th century. No trees block the view of the Italianate flats lining the 16th Street slope up to Castro Street. In this 1950s shot, some of the buildings have already been “modernized” with stucco or Transite siding.

I remember my father talking about drinking with my godfather in upper Market and Eureka Valley bars around 1960, how it was a rough neighborhood, and how longshoremen in those bars were as likely to take a swing at you as buy you a round.

Despite working in a business on Polk Street in the early 1970s, my father rarely acknowledged the existence of LGBTQ+ people, but when talking about the Castro District he’d always make a point of crediting gay men for fixing it up.

Thank you, gay men. ◊

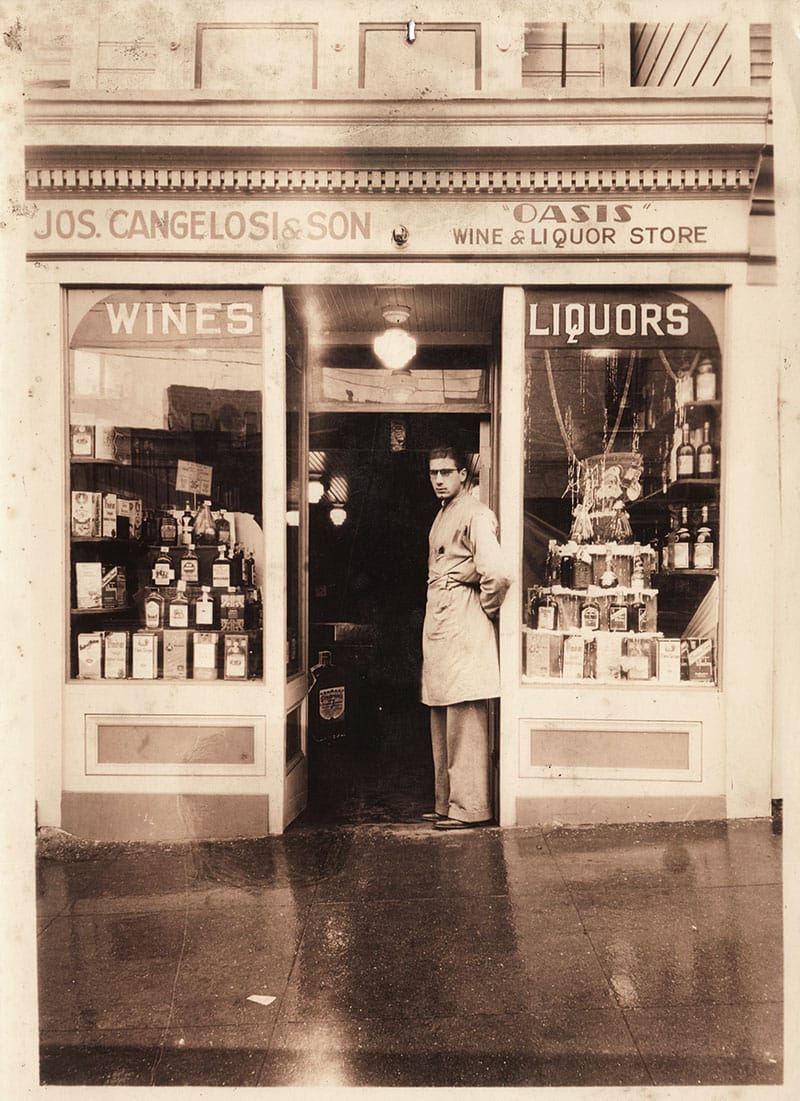

Oasis Liquors, 1930s

Vincent Cangelosi stands in the doorway of Oasis Liquors in Eureka Valley in the 1930s, the son of “Joseph Cangelosi & Son.” When father Joseph became ill in the early 1930s, he worried about how his wife, Pearl, would support herself, so he turned the garage shed in front of their Victorian house at 4251 18th Street into a dual storefront. One space he rented to a barber and in the other established Oasis Liquors. Pearl sold wine, beer, and candy there for decades. “It barely made money at all,” her granddaughter Yvonne remembered, “but it gave her something to do.”

Vin was just 19 years old when his father died. The “lower-middle-class Eureka Valley rough boy” somehow won the heart of Auntie I’s Sunset District daughter, Doris Markstrom, marrying her on Valentine’s Day in 1936. They had their first child, Robert “Bob” Joseph Cangelosi in 1938 and their daughter Yvonne in 1942. The family lived behind and above the liquor store. Doris helped with the store’s books. A small backyard held a massive cherry tree for Bob and Yvonne to climb.

“We ran everywhere and only came home when the church bells rang at Most Holy Redeemer at noon for lunch and then again at five o’clock for dinner.” Their cousins, the Johnsons, lived just a block away on 19th Street. Bob used to play tackle football at Dolores Park and softball with his friend Willie Woo at Eureka Valley playground around the corner. Occasionally boys from Noe Valley—“Carrying chains and boards with nails!”—would come over the hill to fight the Eureka Valley kids. Second base of the softball field acted as the meeting place for battle.

The neighborhood was notably racist then. Bob once saw a black kid step off a bus on Castro Street only to be immediately set upon by a gang of locals who chased him up the hill in the direction of 24th Street.

Eureka Valley transformed into the Castro in the 1970s. Almost all the old businesses faded away, including Oasis. After Pearl died, the family began renting the liquor store space to a variety of businesses and it is currently occupied by a truffle and ice cream store.

When the Pride parades began in the 1970s, Yvonne and her cousin Sharon Johnson would camp out on the roof of the storefront drinking wine and toasting a new era. Some member or other of the family lived on the property until 2010, when it was finally sold. ◊

Donovan’s Saloon, 1880s

As you sped down the ramp off the Central Freeway to the ground, your 1969 Cougar (if you were us) headed straight at this building on the corner of Fell and Laguna Streets. Somehow after 40 years of Detroit steel going too fast and trying to yank left for the park panhandle the building survives with a hummus restaurant on the ground floor.

Street trees now block a lot of this scene from 1885. And you are probably still driving too fast through this intersection. Next time you are there take a closer look and remember Joseph Donovan and the saloon he opened at 500 Fell Street in Hayes Valley. And remember how in the era of building freeways which cleaved neighborhoods and imposed permanent twilight over sidewalks we thought that the rows of beat-up gingerbread west of Van Ness Avenue should be crushed and carted away and that the people who lived in them would thank us for it. Donovan’s building somehow dodged urban renewal.

San Francisco is still a laughably new city. Between fires, earthquakes, and a never-ending boomtown mentality of “progress,” we don’t let ourselves get old. Each humble survivor of our plans—like 500 Fell Street with its three elegant angled bays (and one square one, which feels special somehow), its classical pediment triangles over the windows in-between, and its queenly crowning parapet—is a free time machine ride to a time when a flat over a bar could be beautiful. ◊

Stockton Tunnel

I discovered Dashiell Hammett while working at Waldenbooks. Some deluxe hardback edition of The Maltese Falcon came out, a historical photograph of the San Francisco skyline on its cover. I spent all of my lunch hours over the next two weeks reading it. Soon I was on to Red Harvest, The Thin Man, and The Continental Op. I dabbled with some Raymond Chandler, but his Los Angeles settings made him seem a rival, the Dodgers to our Giants.

I already had a fedora I’d been wearing since high school when the occasion seemed appropriate. (Note: for a 16-year-old boy, there is never an appropriate occasion.) Hammett inspired me to ask for a trench coat for Christmas. I couldn’t afford to eat at John’s Grill for lunch, although I could walk by it on my way to get a burrito on Powell Street.

The setting where Miles Archer is shot baffled me. I couldn’t figure out how a hillside and a fence existed on Bush and Stockton Street because to 18-year-old me the world I knew had existed forever. The Stockton Tunnel had been carved by the gods. Ancients had erected the high wall of buildings running from its portal to Sutter Street.

I was too young to know about change. That a streetcar once ran through the tunnel amazed and excited me. I had always been interested in the past, in history, but until Hammett didn’t consider that my own city could have one. ◊

Rain and Neon, 1957

Steaks are just $1.09 at The Westerner on Market Street near 6th Street. It’s a rainy night in April 1957, so getting indoors for some meat or to see Lauren Bacall in Designing Woman is a good idea. If we don’t want to run across the street to the Warfield or the Cinema—Lucrezia Borgia sounds like it could be a good bad movie—we can just make a left into the St. Francis Cinema and see something in Technicolor©.

The Warfield is still with us in 2023, as is the Cinema building, which last I looked, was the Crazy Horse strip club. I went in there once in the early 1980s after school when it was called the Crest or the Electric or something, and saw… well, I don’t remember. Some teenage boy drivel like Porky’s. Rich Lanier and I walked there from Sacred Heart High School at Ellis and Franklin through the middle of the Tenderloin. We’d sometimes window shop for sheeny polyester suit coats in the big discount clothing stores on Market.

The city has been trying to fix mid-Market Street my whole life. Designating it as an arts zone didn’t work. Giving tech companies giant tax breaks didn’t work. Banning automobiles from Market Street didn’t work. Hoping new condominium towers will do the job seems to be the present plan.

The big movie theaters aren’t coming back, but maybe we just need to re-embrace neon. Instead of businesses putting up signs, let’s do the opposite. Erect blinking animated old-fashioned marquees with seductive words like “Palace,” “Elite,” and “Acme.” Hose down the streets each night to give them a reflective sheen. Watch the people come and fight to sign leases. ◊

Quarters Date

A visit to the Musée Mécanique in the basement of the Cliff House made for the perfect first date. Do you dislike walking through a damp concrete-floored hallway smelling of machine oil and echoing with bells, chimes, clunks, ratchet-turns, and recorded laughter? Are you repelled by grotesque automatons of leering sailors and gypsy fortune tellers, shy about yanking iron handles or peering into varnished wooden windows? Will you pass up trying to beat me in one game of Galaga? Do you think by spending an hour and a roll of quarters on antique music boxes, player pianos, and pinball games I am being cheap?

If so, I’m probably not the guy for you.

Not that this was a test or I expected the Musée to be everybody’s thing. Obviously, time on the woman’s turf, in her world, in her happy place, us together there, would have to be part of the program, either that day or on another date. But a talking stroll around Lands End, Sutro Heights, and a stop in the Musée summed me up very well. I liked being outside and games and the past. I sought places that felt secret and unexpected and better when shared. Slam that lever and get the steel ball past Ducky Medwick in left field.

On my first date with Nancy, after we’d walked 2 ½ miles, hit Park Bowl and the Mad Dog in the Fog and were standing at Haight and Fillmore, she said to me, “Where can we go play some arcade games?” ◊

Keeping Score

San Francisco Story project launch: June 1, 2022

Wednesday posts missed by Woody so far: 0

Subscribers as of November 1, 2023: 915

“Friends of Woody” subscribers: 206

2023 Woody and Nancy trips out of the country: 2

Of those, number with ancient pyramids: 2

Times in 2023 Nancy turned 60 at an ancient pyramid site and blew out a candle on a birthday croissant provided by wacky local guide: 1

That’s it! Thank you Friends of Woody for all your support (of all kinds) in 2023 and here is to a great 2024.

Notes

“Montgomery Avenue,” San Francisco Examiner, January 28, 1870, pg. 2.

“Yellow Dogs Safe on Tehama Street,” San Francisco Call, May 31, 1896, pg. 18.

“Ball Captain Hurt, San Francisco Bulletin, August 6, 1921, pg. 18.

More information on Joseph Selle at https://andreweskind.com, plus I wrote more in this San Francisco Story post.