Selling Silver Terrace

Photographer Eadweard Muybridge had a job to do in southeast San Francisco in 1869.

Photographer Eadweard Muybridge was the father of the motion picture. The fields of animation and film owe a great debt to his 19th century photographic studies of motion. He even has a statue at the Letterman Digital Arts Center in the Presidio of San Francisco.

But Muybridge’s experiments in detecting the patterns of movement through sequential photographs came in the 1880s and 1890s.

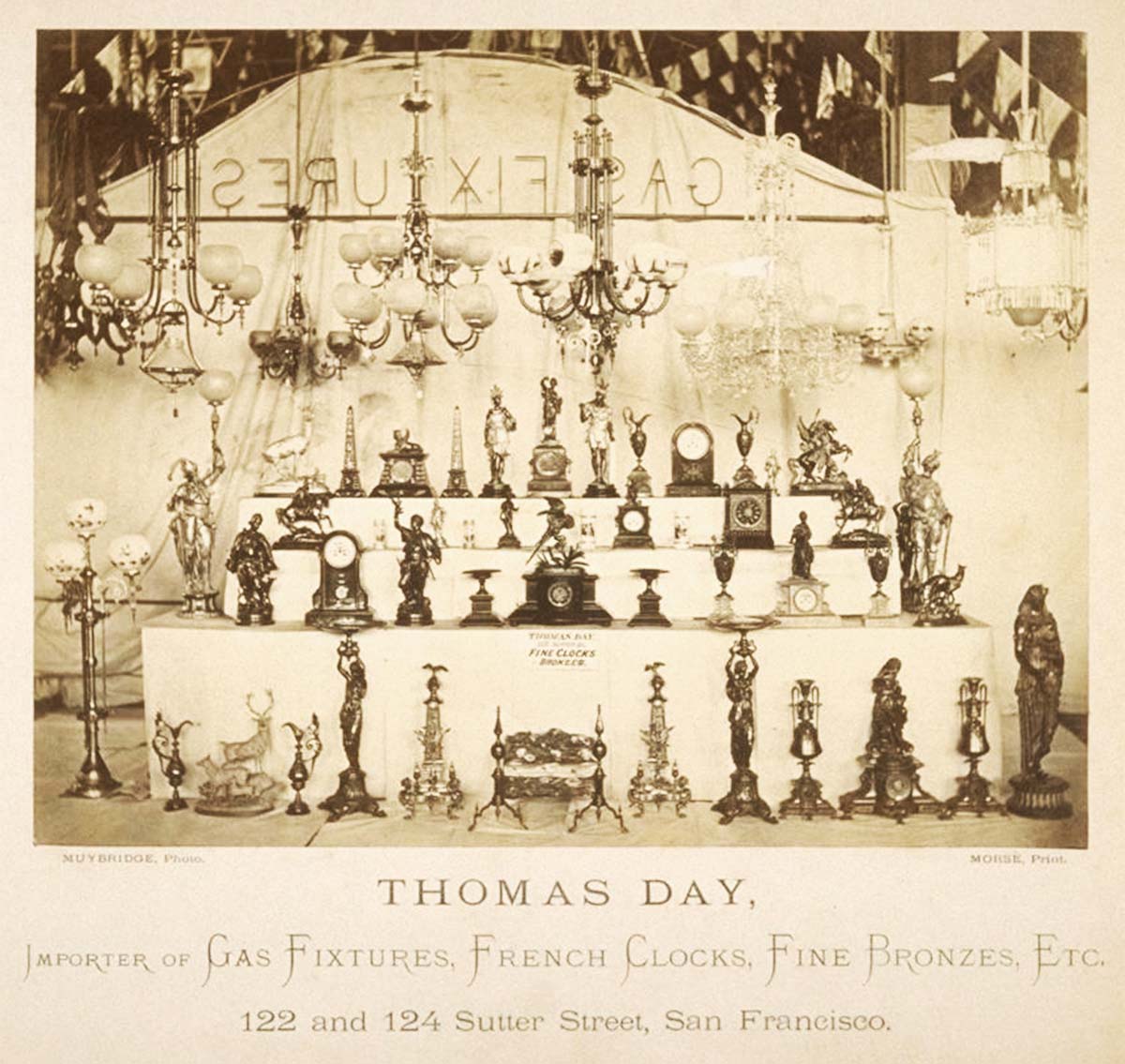

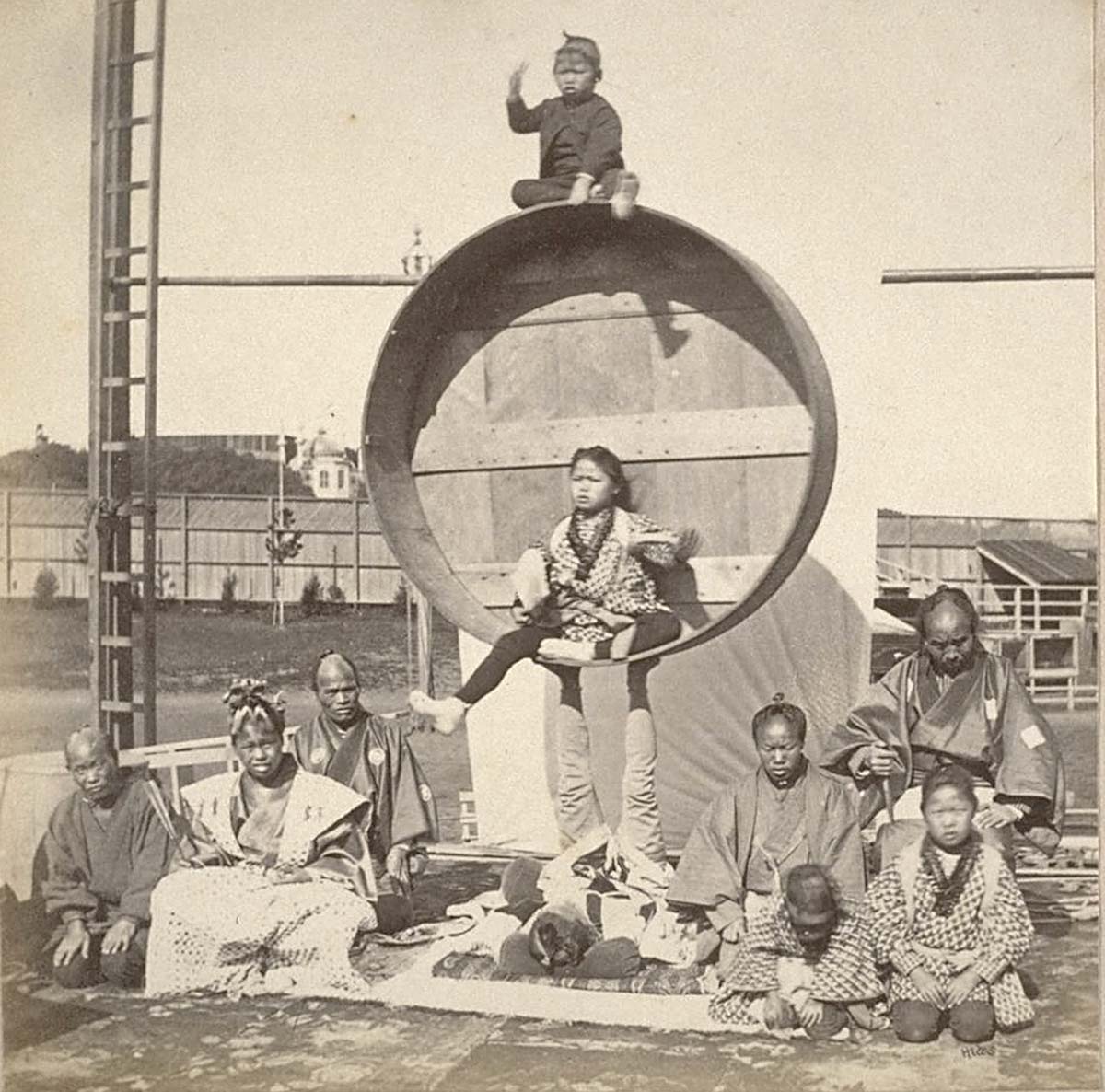

At the end of the 1860s, he was a photographer trying to make a buck, hired to shoot ads for sidewalk pavement and gas fixtures, as well as promo photos for the Woodward’s Gardens amusement park in the Mission District.

Making a living is why Muybridge found himself lugging his heavy equipment out to the grassy slopes of a muddy estuary in “South San Francisco” in the winter of 1869.

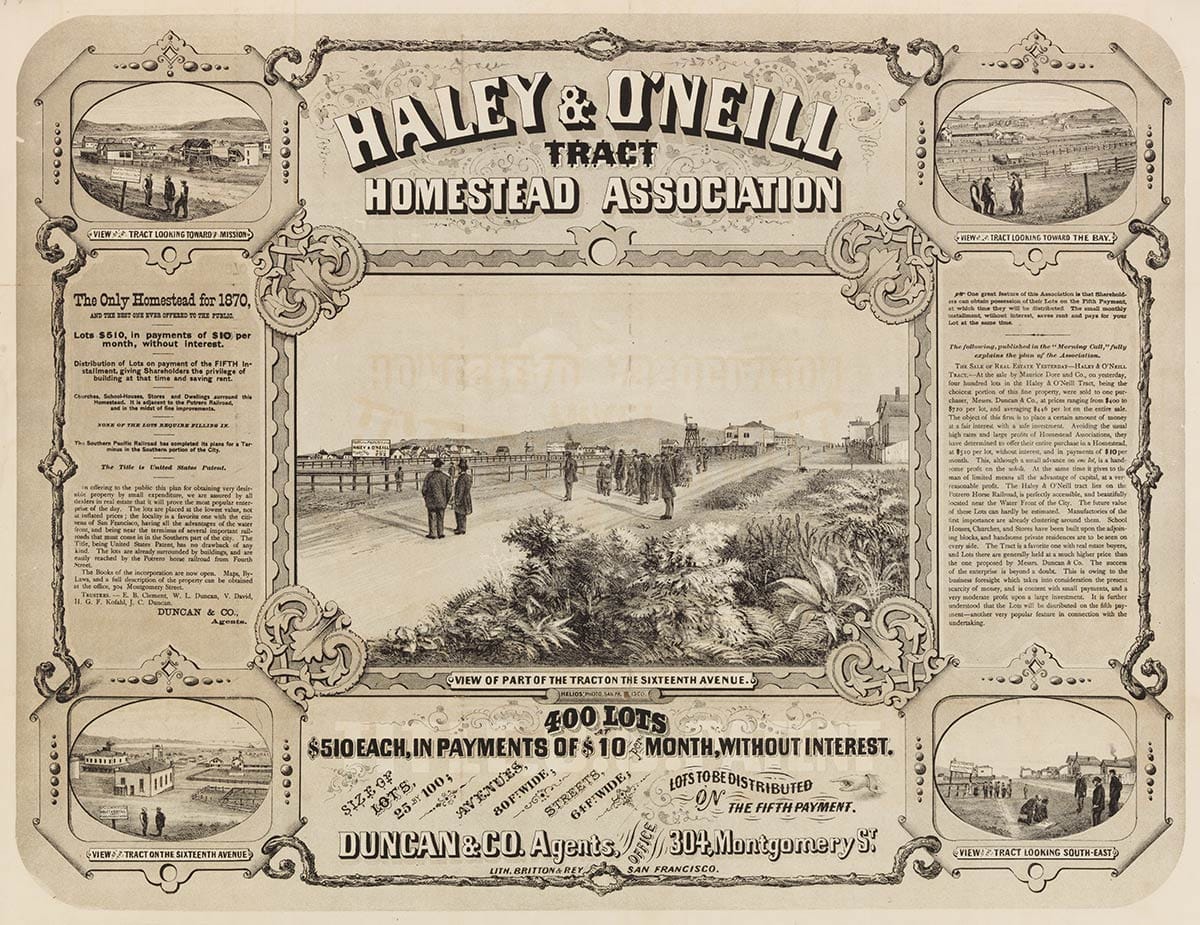

Duncan & Co. had grabbed a few hundred countryside lots in a land auction and was now trying to flip the investment as a homestead association. The Duncan boys wanted some slick promotional material and were willing to invest in photography, a big deal in 1869.

The land was in the Haley & O’Neill tract on the south side of Islais Creek. Today, we San Franciscans lump that area into the neighborhood of Silver Terrace.

Silver Terrace

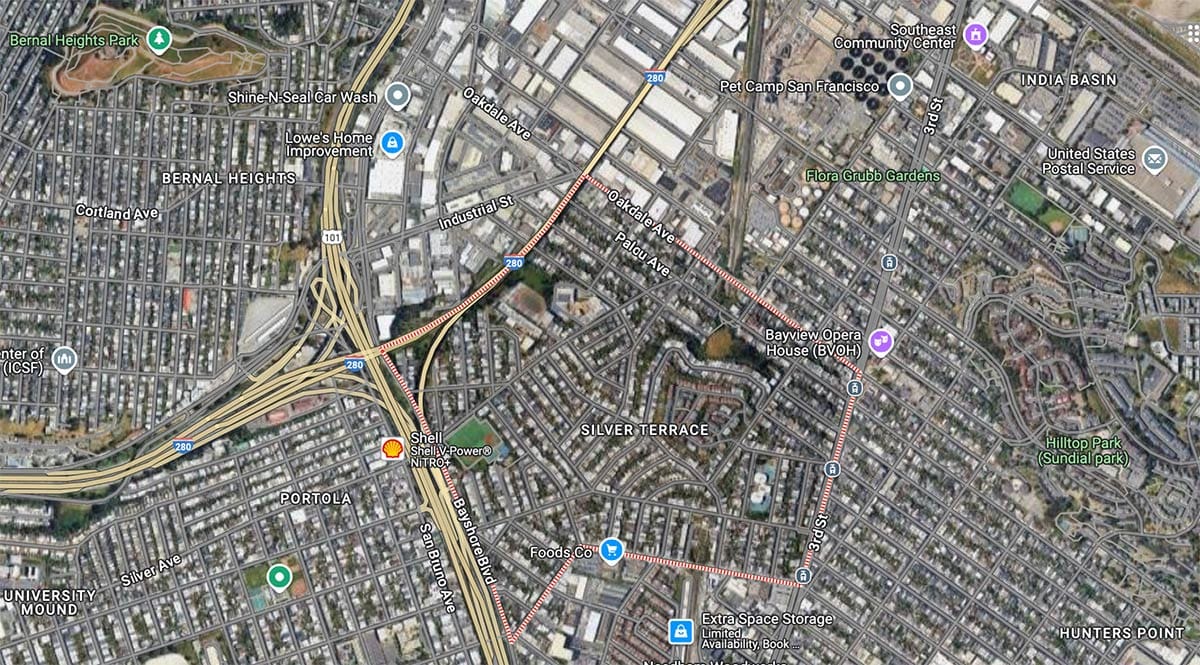

If you don’t live near there, you may be a bit vague on the location of Silver Terrace, which is mostly residential and somewhat of an island isolated by freeways, rail lines, and strange street grids.

It is in the city proper, not the later-incorporated town of South San Francisco. (Names in southeastern San Francisco—streets, neighborhoods, hills—were all very fluid and changing in the 19th century.)

Here’s how most of you see it: you’re driving south on Highway 101 and have just passed hospital curve and Potrero Hill. Bayshore Boulevard and a sea of warehouses open up on your left and Bernal Hill is on your right. You are about to hit that tangle of ramps and overpasses and the intersection of Hwy 280.

Off to the east is a bumpy ridge line with the prominent building of Thurgood Marshall High School. That ridge and the tangle of streets encircling it is Silver Terrace.

The name dates back to the late 1850s. There was never any literal silver ore in Silver Terrace and—while not a bad guess if you thought it—the name wasn’t coined by real estate hawkers to evoke riches. It once belonged to a Mr. Silver .

Joseph S. Silver claimed title to sections around the ridge as part of a land rush shortly after the Gold Rush in the 1850s.

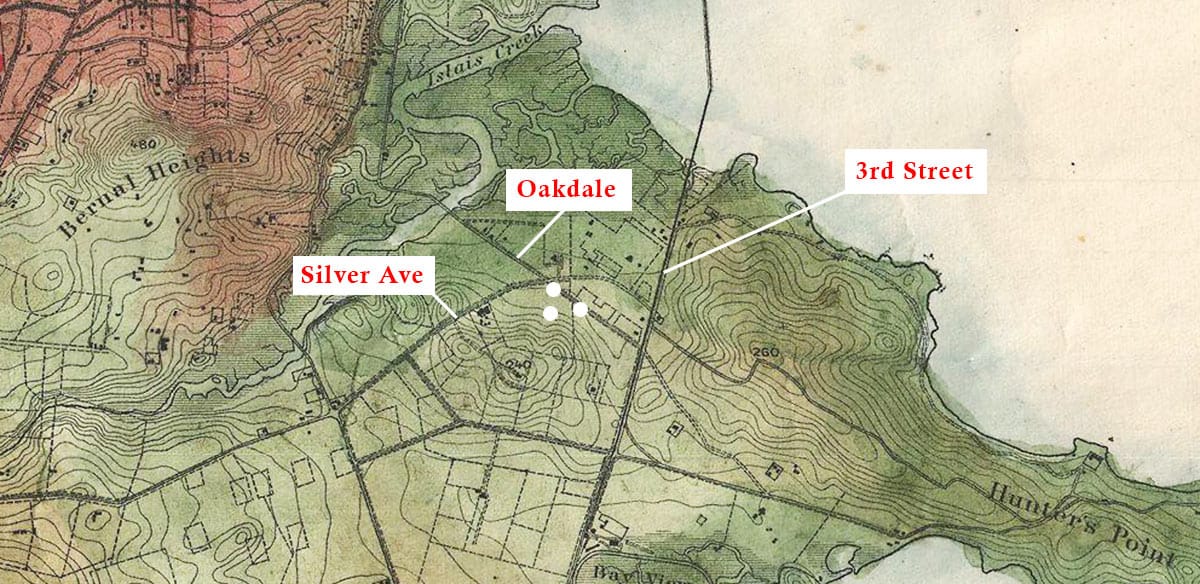

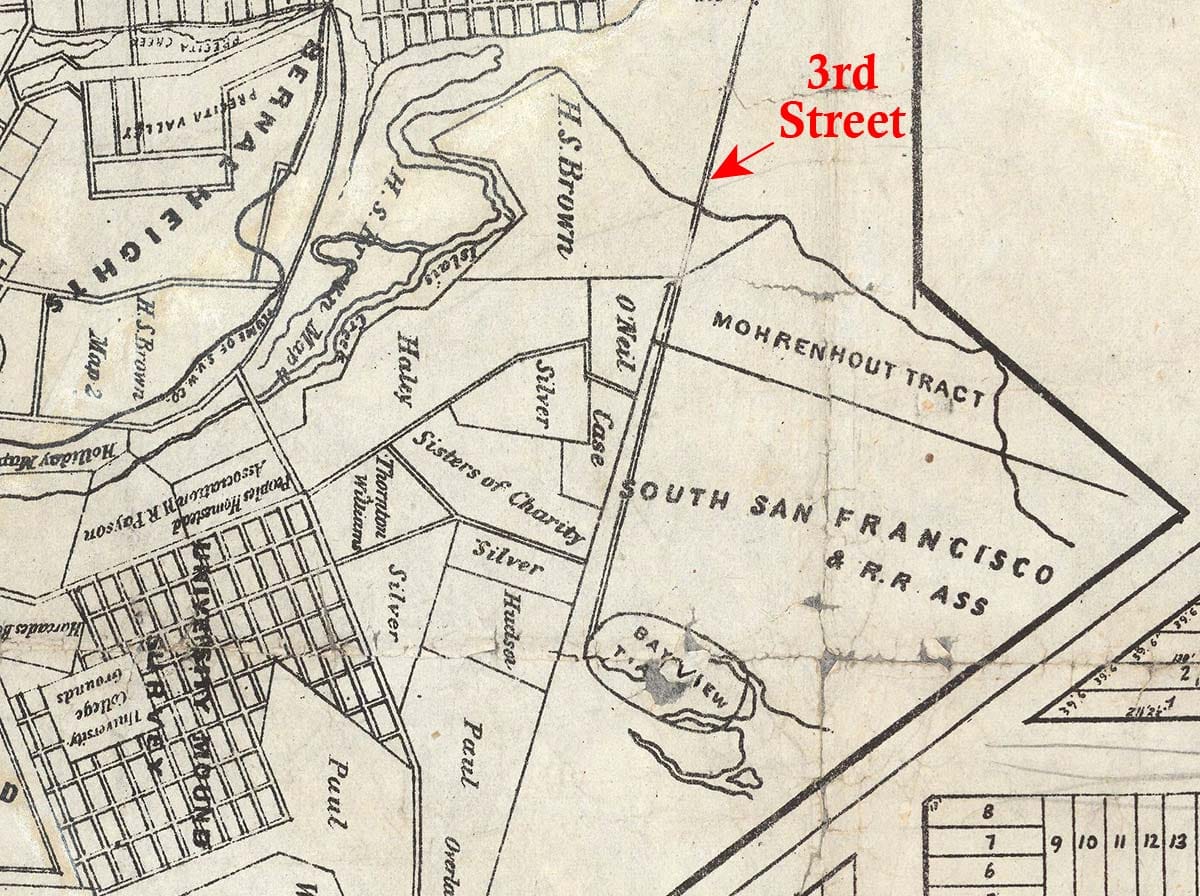

Mexican ranches were eaten up by invading Americans—squatters and speculators who claimed or bought tracts from family members or intermediaries. Silver and his partners acquired and fenced in a tract between the San Bruno turnpike road on the west (now San Bruno Avenue) and what is today 3rd Street in Bayview on the east.

Years of court cases followed to clear up the conflicting Mexican land grabs. Silver held onto his bit of the old Rincon de la Salinas y Potrero Viejo rancho, but had his dust-ups defending it.

In 1859, his neighbor Horatio Paul (for whom modern Paul Avenue is named) claimed Silver illegally tried to sell part of his land. The same year, speculators associated with Hunters Point cut a road across Silver’s plot. He filed a law suit. His antagonists called him “obnoxious to the whole community” in a resolution published in two newspapers.

On October 6, 1859, the parties ran into each other on the contested road. The wife of one of the Hunters Point contestants was present. An argument broke out.

The Bulletin reported that “in the course of the difficulty, […] the lady’s husband was thrown down and beaten, and it is said that Mr. Silver drew a pistol and snapped it at him. The wife, at this, jumped from the carriage with a heavy whip in the hand, and made a vigorous application of it upon Silver’s head and face.”

Drama, drama, drama, but in the end, Silver won the case.

Haley, O’Neill, and Muybridge

Silver seemed to have gotten along better with his neighbor, John J. Haley (the prime mover of creating Long Bridge), who teamed up with Edward O’Neill to start selling their tracts abutting Silver on the northeast.

Land agents Duncan & Co. bought more than 400 of these lots and launched a homestead association to attract investors in February 1870. All but a couple of the streets existed only on paper and many of the lots lay in marshland, but the promoters crowed that “churches, school-houses, stores and dwellings surround this homestead.”

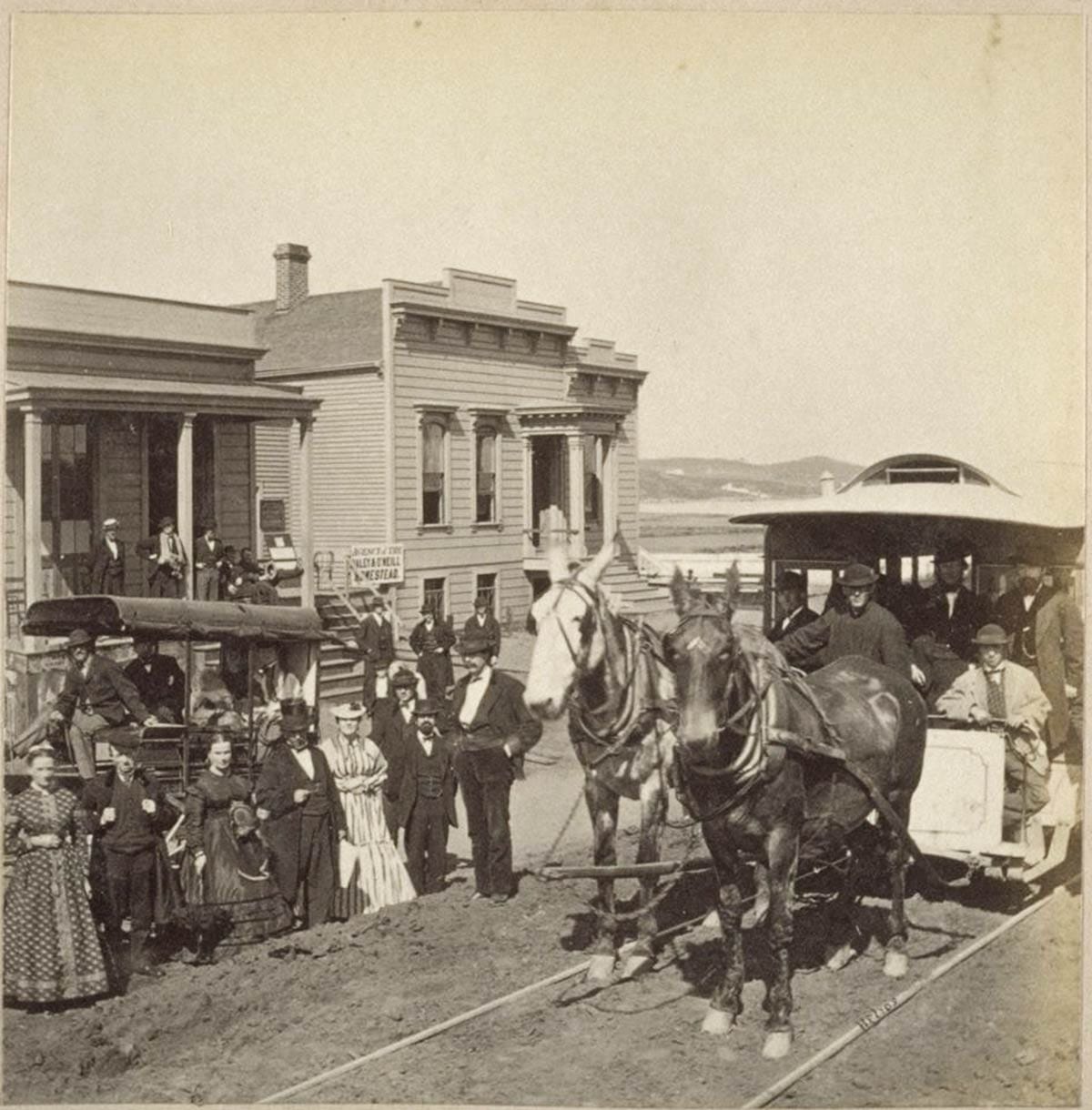

Also promised by the promoters: excellent transit connections to downtown by a new horse car line (Haley was a big backer of the new company).

The Potrero & Bay View Railroad horse car line, begun in 1866, was supposed to deliver you from downtown all the way to today’s 3rd Street and Gilman Avenue, with the line running on two long bridges across Mission Bay and the Islais Creek marsh. (Most of today’s 3rd Street started life as bridge.)

The long route over mostly empty land meant the line was doomed from the start. It never completed its projected route, but ran sporadically into the 1890s.

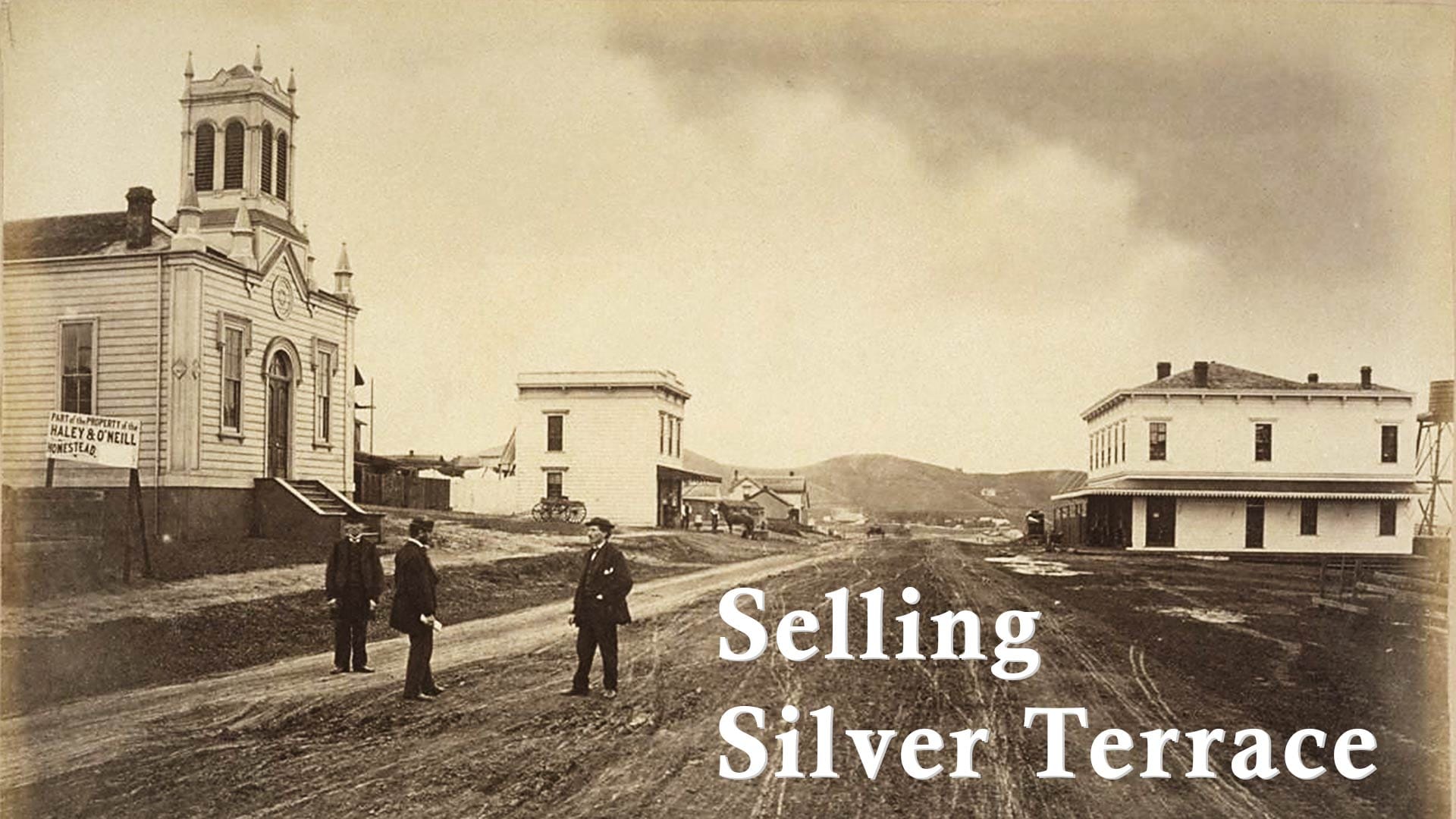

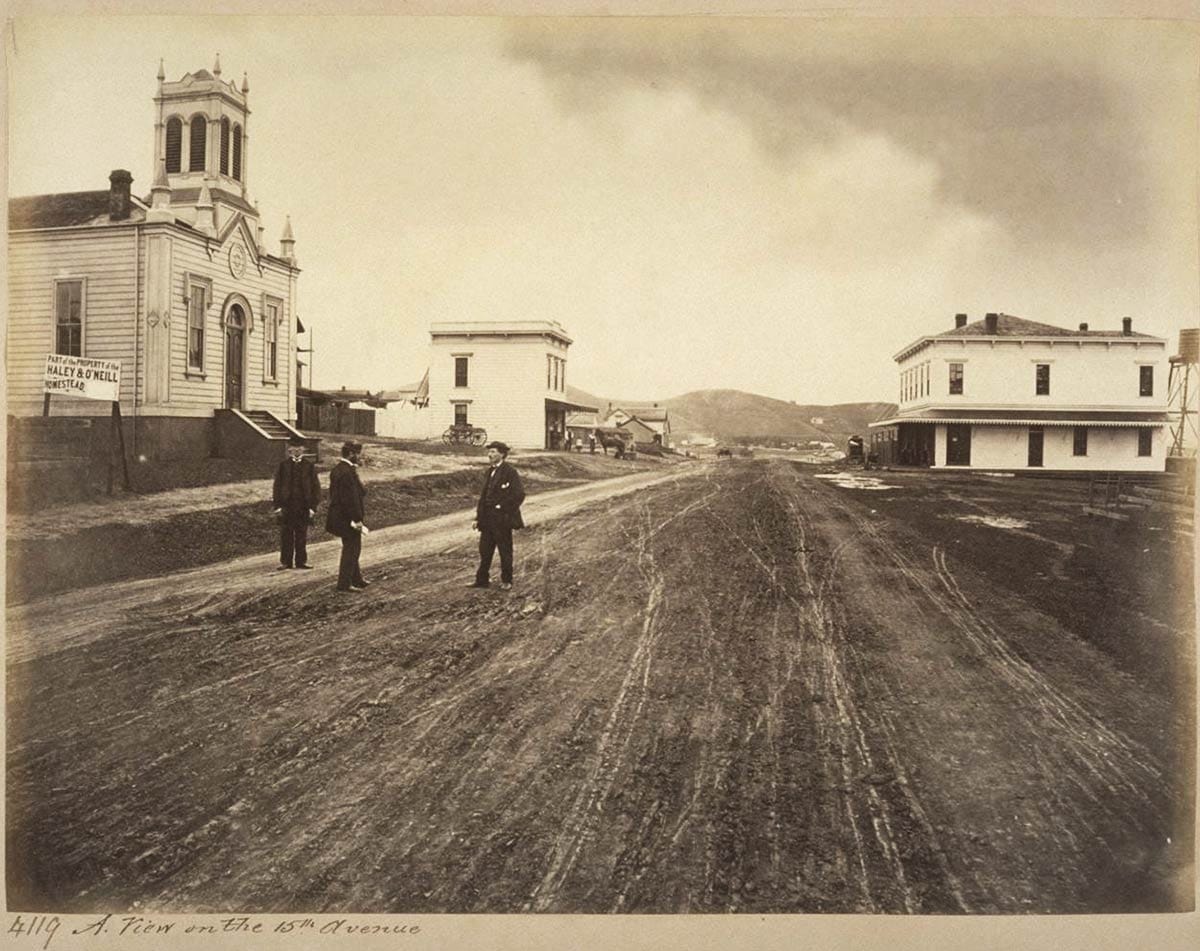

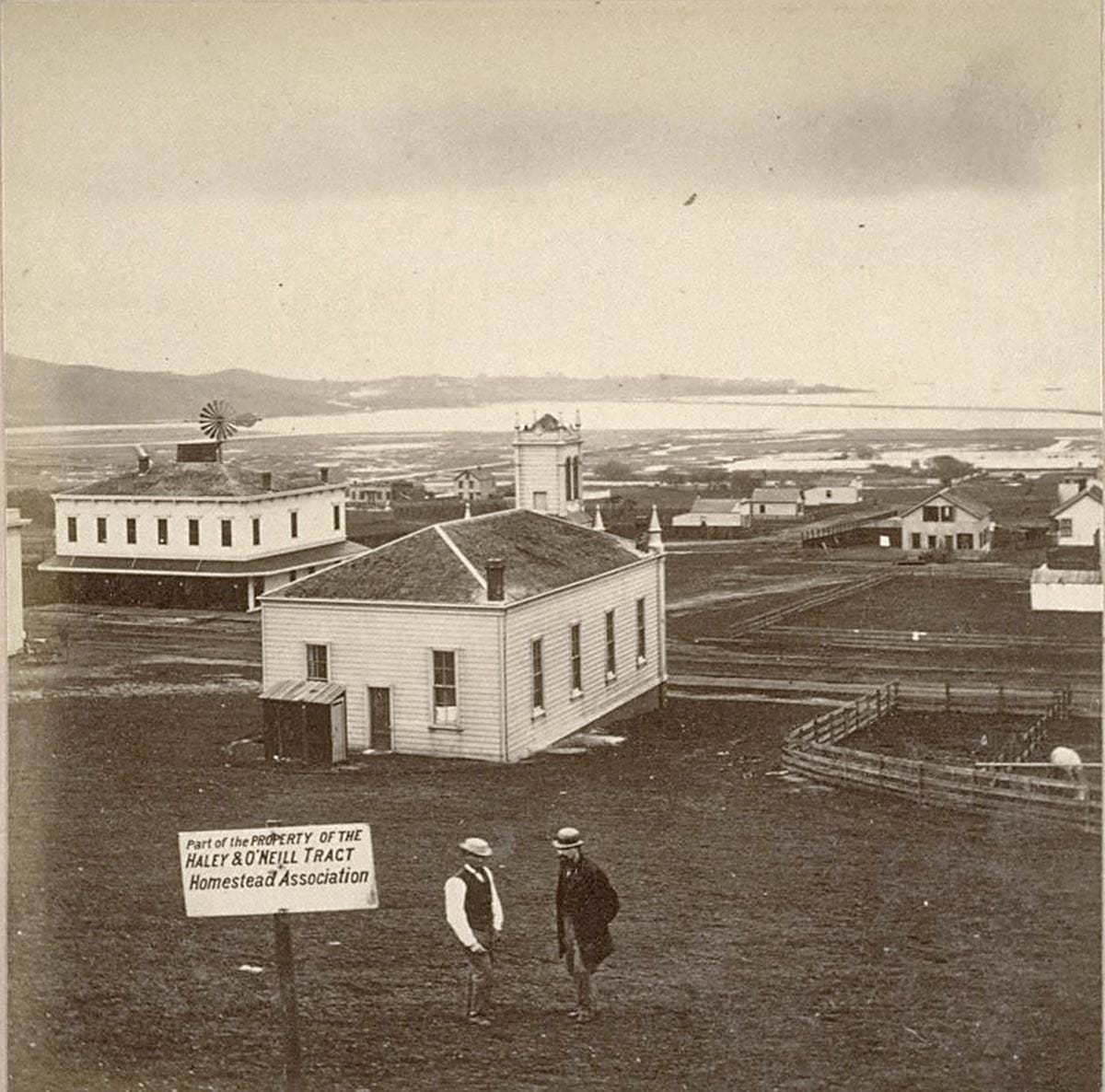

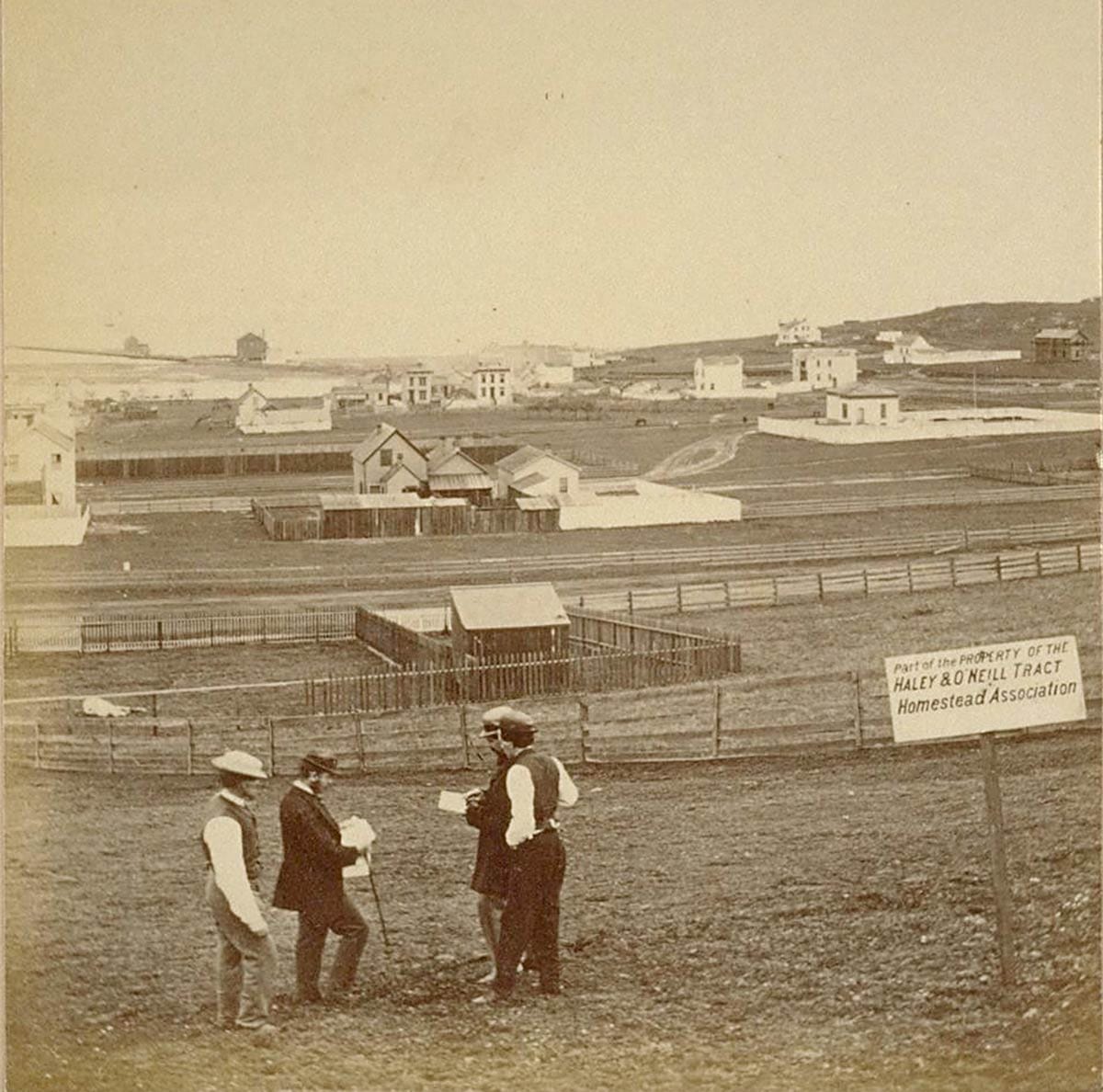

Photographer Muybridge’s job was to show the site to best advantage, even though most of the land was just fields, marsh, and signs demarcating lots. He framed his shots to show what little was standing in the area. A new Methodist Episcopal church and roadhouse on the one real road graded through the property gave the best sense of neighborhood:

What was then named South 15th Avenue is today’s Oakdale Avenue. The church stood just east of modern Phelps Avenue, where Silver Avenue then curved in to meet the road. The site still holds a church, Saint Paul Tabernacle Baptist Church. Here’s a contemporary view roughly in the same place:

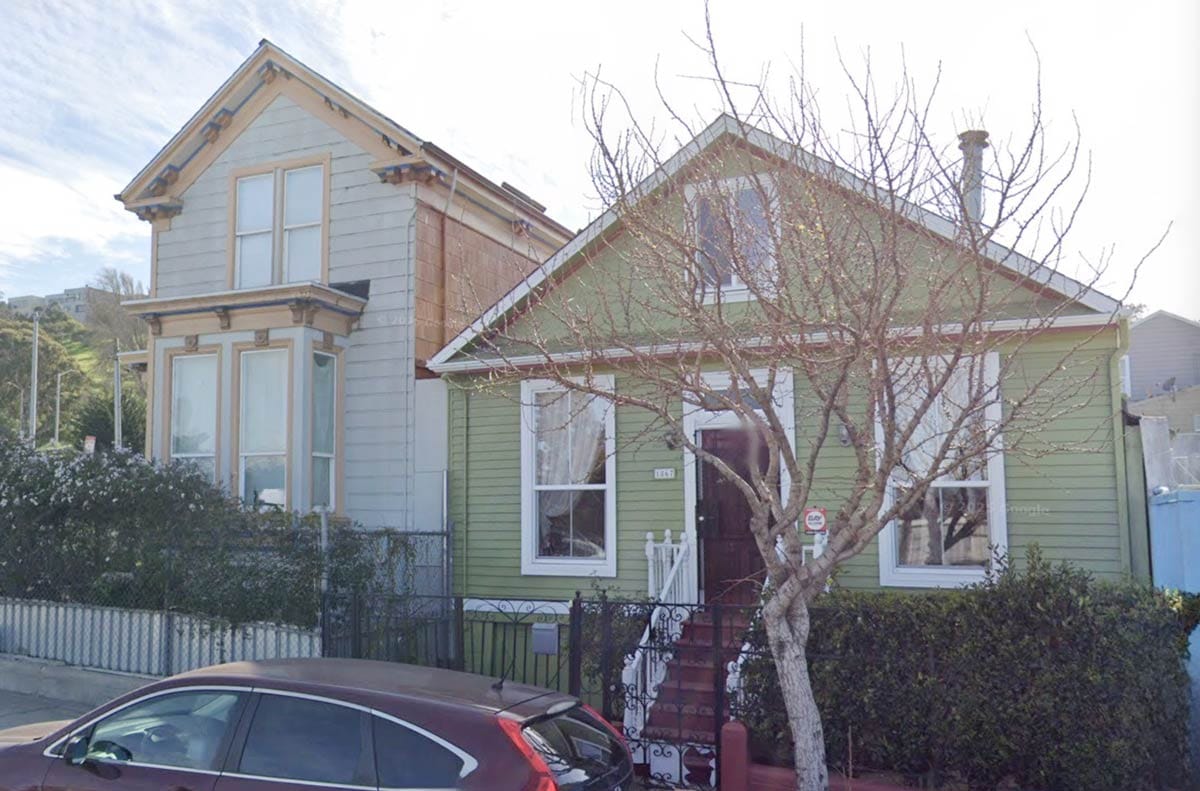

Muybridge walked west close to the corner of Quint Street today to take a shot looking the other direction. The promoters did a little scene for him, kneeling to review what looks like a sales book. At least two of the buildings visible, 1863 and 1867 Oakdale, are still standing today:

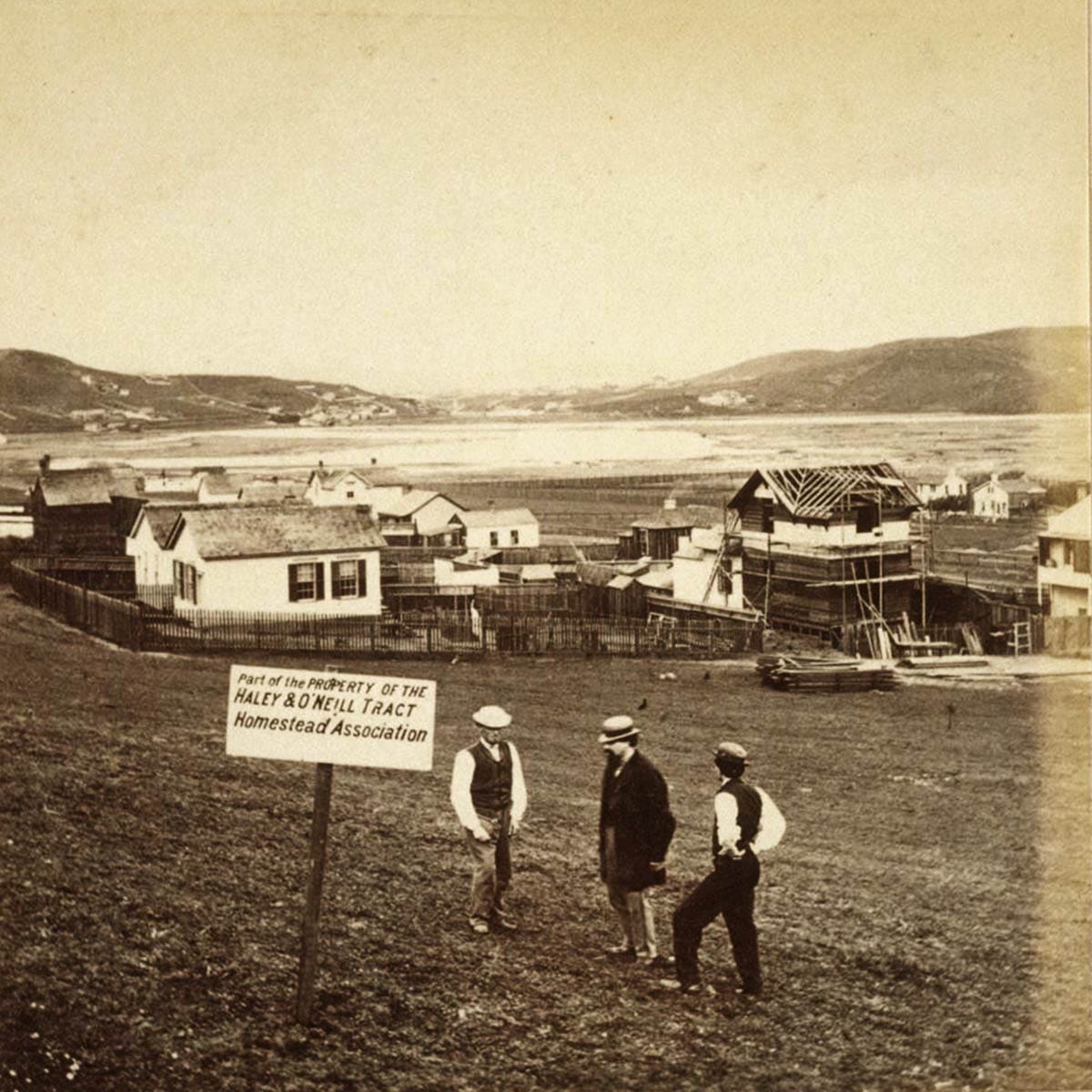

Uphill near today’s Palou Avenue, Muybridge gives us a rare early view of the vast wetland cove fed by Islais and smaller creeks before it got filled in to give us the warehouse and maintenance yard landscape we have today:

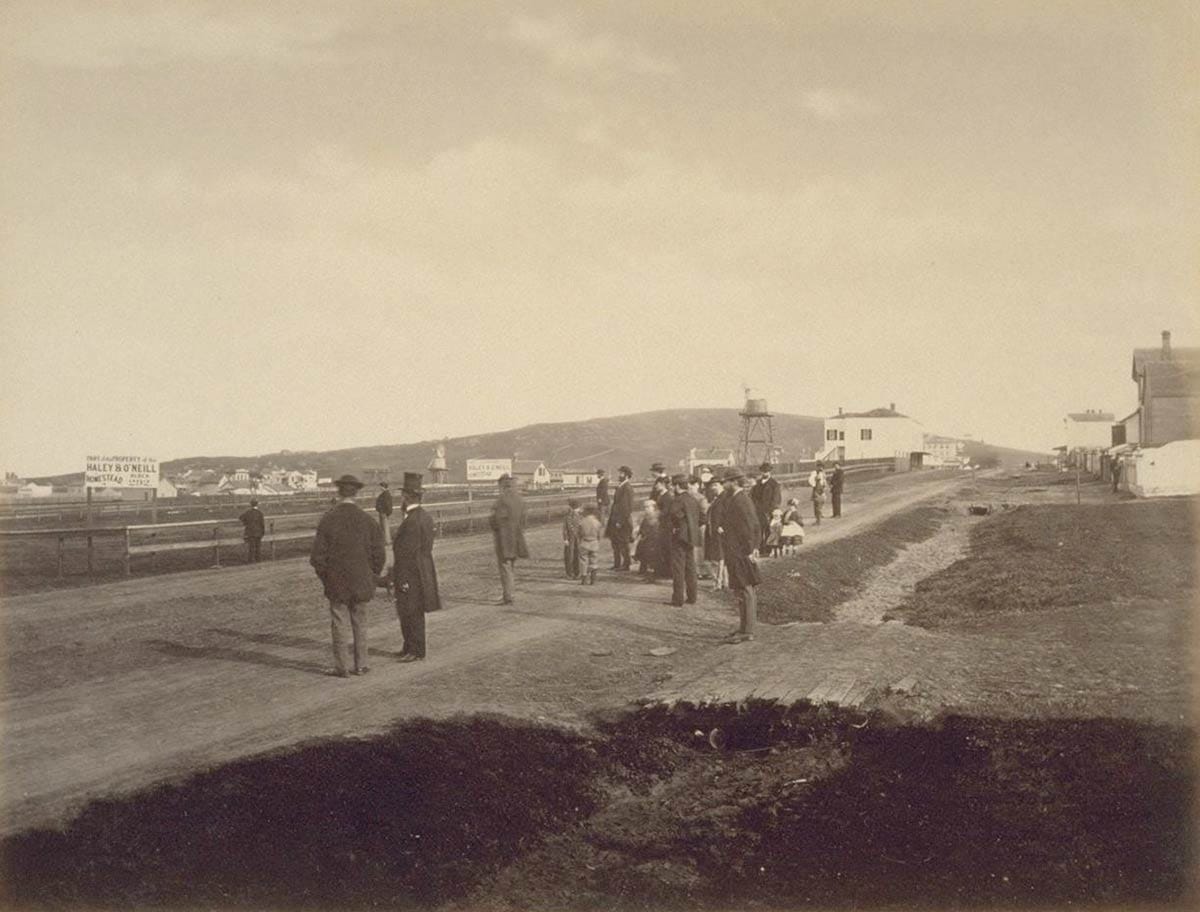

Here’s a shot more to the northeast behind the church:

The Roman Catholic archdiocese had just built a new orphanage at the top of the hill above the Haley & O’Neill tract and such a grand institution had to make an appearance. Muybridge had all the kids of the neighborhood as part of the shot to help evoke the property’s suitability for families.

Next Chapters

Muybridge got married about a year after taking the Haley & O’Neill tract photos. In October 1874 he shot and killed his wife’s lover, a crime he was acquitted of as “justifiable homicide.”

He traveled and photographed in Central America before achieving worldwide fame in the 1880s and 1890s for his photographic studies of motion.

Duncan & Co. seemed to get what they wanted out of the homestead investment at first, but by 1873 were being foreclosed upon for not paying the mortgage on what the partners still held.

Most of the tract wasn’t built upon until the 20th century. But hidden within the streets of the pie made by 3rd Street, Phelps Street, and Palou Avenue are a good number of Haley & O’Neill tract residences, some of the oldest houses in San Francisco.

Woody Beer and Coffee Fund

I owe you a drink. Good-hearted people have advanced us the dough to meet by contributing to the not-a-ponzi-scheme Woody Beer and Coffee Fund. (You might be a good-hearted person, right?)

Let me know when and where you would like to meet!

Sources

“Rencounter on the San Bruno Turnpike,” Daily Evening Bulletin, October 8, 1859, pg. 3.

Resolution, Daily Alta California, October 20, 1859, pg. 2, col. 3.

“Card from Mr. J. S. Silver—Hunter’s Point,” Daily Alta California, October 22, 1859, pg. 1, col. 8.

“Law Intelligence,” San Francisco Herald, November 5, 1859, pg. 2.

Advertisement, Daily Alta California, November 14, 1859, pg. 4, col. 3.

Advertisement, San Francisco Chronicle, February 11, 1870, pg. 2.

“City Notices,” San Francisco Chronicle, February 13, 1870. Pg. 5.