Spirit of Victory

A San Francisco Spanish-American War monument with some muddy messaging.

One hundred and eighteen years ago this week, at 2:30 p.m. on Sunday, August 12, 1906, a new San Francisco monument was unveiled at Van Ness Avenue and Market Street. Twenty years later it would be moved to Dolores and Market Street, where it still stands today.

The California Volunteers monument, an assemblage of bronze figures atop a towering granite pedestal, is dynamic, dramatic, and overall, an allegorical omelet.

A wounded soldier lays splayed out over a cannon, still holding his rifle aloft. A companion stands unnaturally upright beside him holding pistol and sword, defensive, perhaps next to fall.

The pair are overshadowed by a helmeted Valkyrian goddess on a winged charger. Her face is set, merciless. Her cloak arches from her outstretched sword arm, swirling around the standard she carries.

This goddess was described as the “Spirit of Victory,” but she is not triumphant as much as grim and unrelenting. It looks like her steed is about to trample the fallen warrior. She is death in motion, and rather than Victory is really (as one newspaper reported) Bellona, the Roman goddess of war and destruction and conquest, known for her bloodlust and madness in battle.

When the monument was commissioned in 1903, no one knew how appropriate the landscape would be for its future dedication in 1906. San Francisco looked bombed-out after the April 18 earthquake and its following firestorms. The scene behind the ceremony was a charred, rubble-strewn vista of ruins dominated by the skeletal dome of city hall.

A stranger might assume Bellona had done her work here, and done it well.

Commissioned as a memorial to the local dead of the Spanish-American War and paid for by left-over funds subscribed to entertain the returning California Volunteers, the monument embodied—if unintentionally—the ironies and muddy legacies from that conflict.

A Splendid Little War

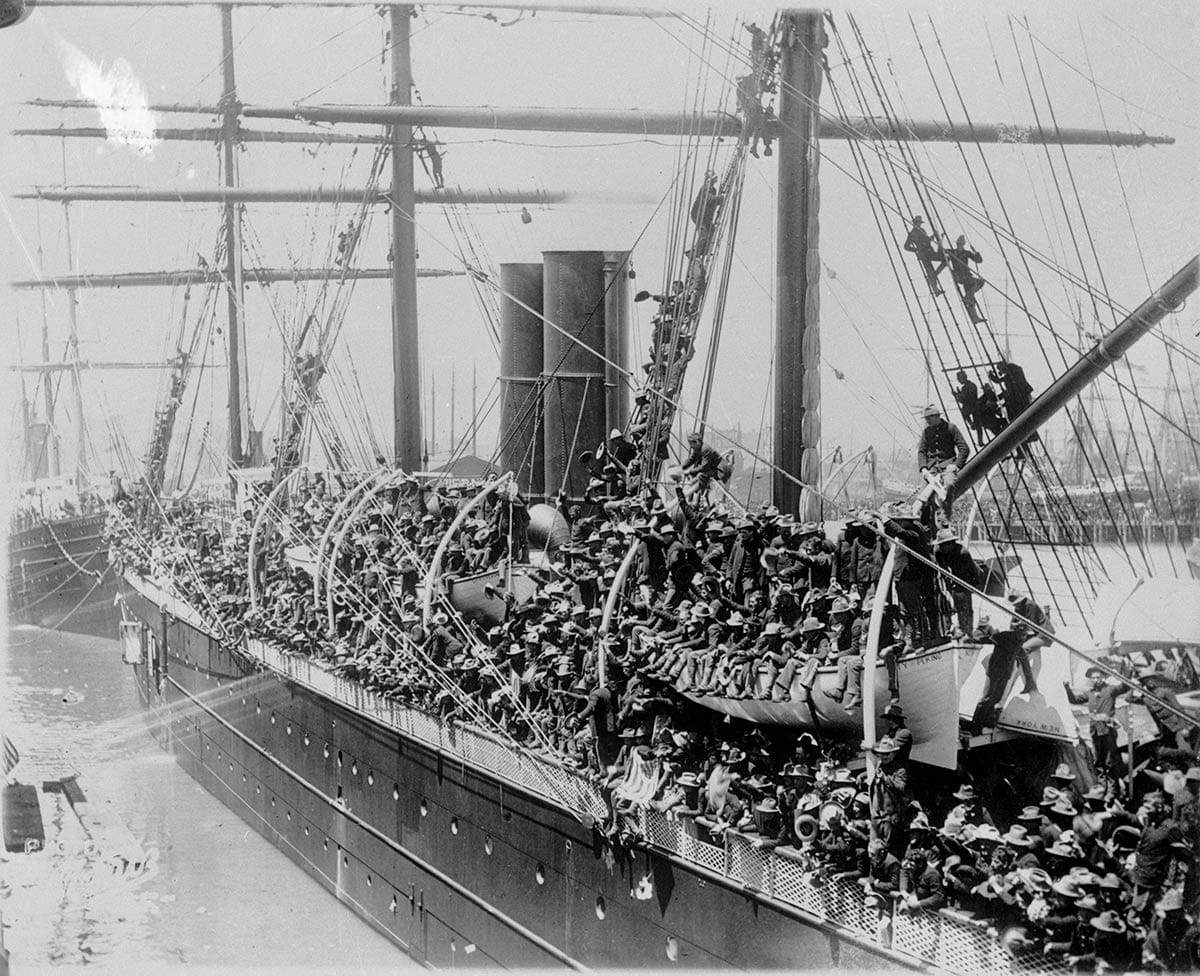

The United States’ self-imposed mission to “free” subjected peoples from the chains of Spanish tyranny, was a 16-week affair, a “splendid little war,” in the words of former Secretary of State John Hay.

In the Philippines it became clear that the conflict was as much about American Imperialism and our desire to be a colonial overlord than any release of oppressed people from bondage. Swash-buckling engagement against Spain ended in weeks, and flipped into a years-long police action to suppress “insurrection” by those we came to free.

Turned out that the Filipino people, who had been fighting a revolutionary war against Spain since 1896, didn’t want to be ruled by the United States either.

Whether sculptor Douglas Tilden intended it or not, the monument he received $24,000 to create reflects the contradictions of the Spanish-American War and the less-talked-about Philippine-American War that followed.

Originally the idea was to list the names of the California Volunteers war dead on the monument base and on the other side a long inscription of the event, ending with “In the service of their country the First California Heavy Artillery lost 103 officers and men. Honor the brave.”

But none of this commemoration of the dead happened. The message that did make the granite pedestal celebrates the enthusiasm to fight, honoring all the California volunteers, noting them as the “First to the Front.”

The pedestal is so tall, most people only see a mythic steed and figure leading with a sword. That wounded soldier seems to be as much a victim to our war fever—symbolized by Bellona’s reckless ride, let us say—than the unseen enemy. And most of the US dead in the conflict died from real disease, by the way.)

The standing companion looks ready to go any direction, forward to fight, or back home to share some bad news.

Is this a memorial to the dead or a bronze celebration of war with a capital W?

The speakers at the 1906 dedication had varying takes.

General James F. Smith, who was commander of the First California Volunteers regiment, and was shortly to become Governor General of the Philippine Islands called it “a monument to the dead, to the dead sons of California who one fair May morning bade farewell forever to all that they held dear and to the strains of martial music sailed away to return no more.”

James D. Phelan believed it “commemorate[ed] the valor” of the volunteers, their “gallantry and devotion.”

Captain Peter T. Riley thought the message was of sacrifice: “This beautiful group will teach forever the lesson of patriotism and will remind our youth that there is no greater honor than to give our lives for the republic.”

The California men who died in the Philippines were not defending our republic.

Many Unmentioned Results

War, any war, puts us all into these false phrases, intentional blind spots, and emotional confusions. Mark Twain articulated such contradictions in The War Prayer, a short piece he wrote at the end of the Philippine-American War, but which was unpublished in his lifetime.

A congregation praying for its country’s departing soldiers beseech God to “watch over our noble young soldiers, and aid, comfort, and encourage them in their patriotic work….”

An emissary from God shows up to interrupt them mid-prayer: “When you have prayed for victory,” he tells them, “you have prayed for many unmentioned results which follow victory–must follow it, cannot help but follow it.”

He then enumerates what their prayers for victory mean, an entreaty really for the Lord to:

“...help us to tear their soldiers to bloody shreds with our shells; help us to cover their smiling fields with the pale forms of their patriot dead; help us to drown the thunder of the guns with the shrieks of their wounded, writhing in pain; help us to lay waste their humble homes with a hurricane of fire; help us to wring the hearts of their unoffending widows with unavailing grief; help us to turn them out roofless with little children to wander unfriended the wastes of their desolated land in rags and hunger and thirst, sports of the sun flames of summer and the icy winds of winter, broken in spirit, worn with travail, imploring Thee for the refuge of the grave and denied it — for our sakes who adore Thee, Lord, blast their hopes, blight their lives, protract their bitter pilgrimage, make heavy their steps, water their way with their tears, stain the white snow with the blood of their wounded feet! We ask it, in the spirit of love, of Him Who is the Source of Love, and Who is the ever-faithful refuge and friend of all that are sore beset and seek His aid with humble and contrite hearts. Amen.”

The piece finishes “It was believed afterward that the man was a lunatic, because there was no sense in what he said.”

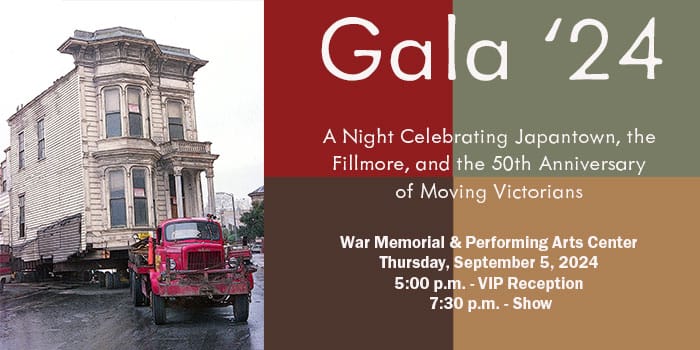

Join me on September 5th

The program for the San Francisco Heritage annual gala is coming together wonderfully. I hope you can join me on Thursday, September 5, 2024 at the War Memorial & Performing Arts Center. There are still $250 individual tickets for the whole evening with VIP reception—but you can also just sign up for the big show in Herbst Theater for just $50.

Oh, and there’s a silent auction now too. Get art, go on history walks, or win your very own San Francisco Directory from the 1910s to look up old relatives and do research just like the pros. (The pros who like the smell of books.)

Can’t make it because you live in Copenhagen or Tampa? Consider donating to the nonprofit to send a community member to the event: scroll a smidge on this page.

Woody Beer and Coffee Fund

I think these weekly posts are getting longer? Probably a bad sign. I should reflect on the matter over a drink and some conversation, and thanks to the contribution by Todd W. (F.O.W.) to the Woody Beer and Coffee Fund, I can! Thanks Todd.

I am behind on scheduling meet-ups with some of you, but fear-not, I’ve almost got a handle on everything. Yes, everything.

Sources

“Tilden’s Model the One Chosen,” San Francisco Chronicle, January 31, 1903., pg. 14.

“Monument to Honor Spanish War Heroes,” San Francisco Call, January 31, 1903, pg. 6.

Will Sparks, “Studio Building for Artists Proposed for San Francisco,” San Francisco Call, August 5, 1906. Pg. 27.

“Will Unveil New Statue on Sunday,” San Francisco Call, August 6, 1906, pg. 5.

“Ready to Dedicate the Monument,” San Francisco Call, August 12, 1906, pg. 25.

“Monument Dedicated to Memory of California Volunteers,” San Francisco Call, August 13, 1906, pg. 12.

“Monument to the California Volunteers is Unveiled with Fitting Ceremonies,” San Francisco Chronicle, August 13, 1906, pg. 1.