The Cobweb Palace

Abe Warner's cobweb-filled saloon in San Francisco's North Point neighborhood was captured on film before demolition and now we know when.

Decorating drinking establishments with the odd, curious, and random is not a new or uncommon practice. Your local dive may have a broken accordion or a jackalope behind the bar, but Spec’s Twelve Adler Museum & Café in North Beach is San Francisco’s reigning champion of tavern as museum of the bizarre.

Across Columbus Avenue from City Lights books, Spec’s is a hole-in-the wall retreat for both scoffing socialists and the poetically precious (“Look at me. I’m a beatnik!”) with an interior design that may be primarily described as “Nautical Eclecticism.” (Just made that up.)

Clipper ship prints and models, tiki totems, signal flags, life preservers, shark jaws, and a walrus penis are on display for tipsy perusal. There are numerous exceptions to the maritime motif—Victorian ads, license plates, wise-ass bumper stickers, and a satirical Egyptian sarcophagus of bar founder Specs Simmons—but happily Spec’s clientele is a charitable and indulgent lot.

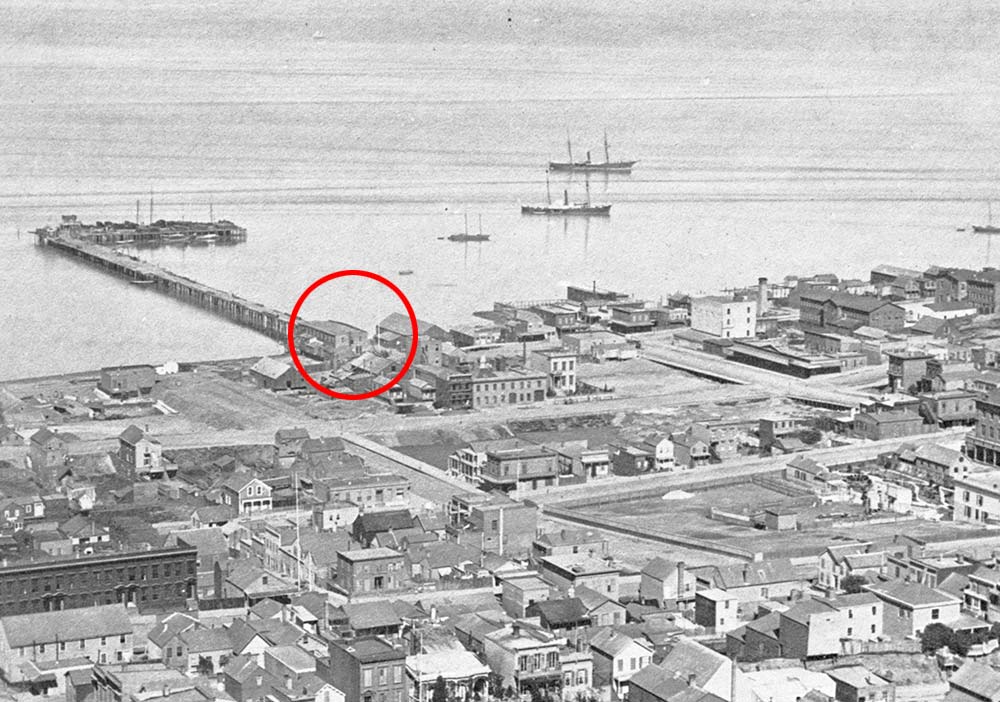

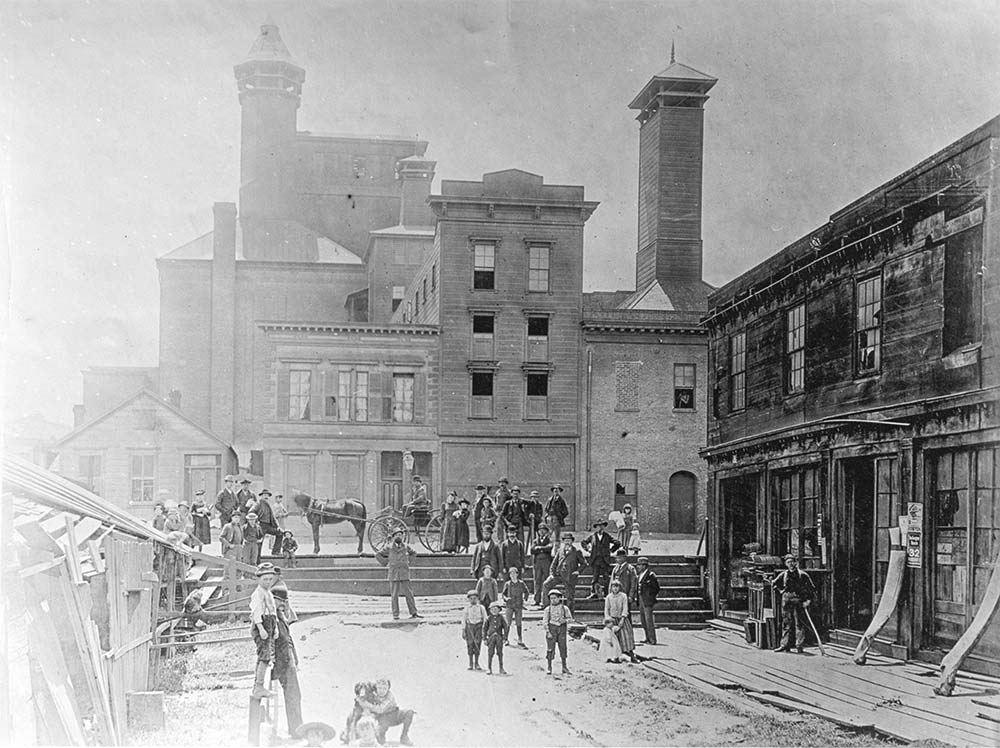

Spec’s spiritual ancestor, remote in time if not distance, was Abe Warner’s Cobweb Palace, which once stood about ¾ of a mile north of Adler Place in a ramshackle building on Meiggs’ Wharf. In the 1850s, before San Francisco had filled in its coves, lagoons, and inlets to become the smooth-edged thumb shape we know today, Meiggs’ Wharf jutted into the bay from the middle of Francisco Street between Powell and Mason Streets. (The story of forger, defrauder, and skip-out-of-towner Harry Meiggs we shall reserve for a future date.)

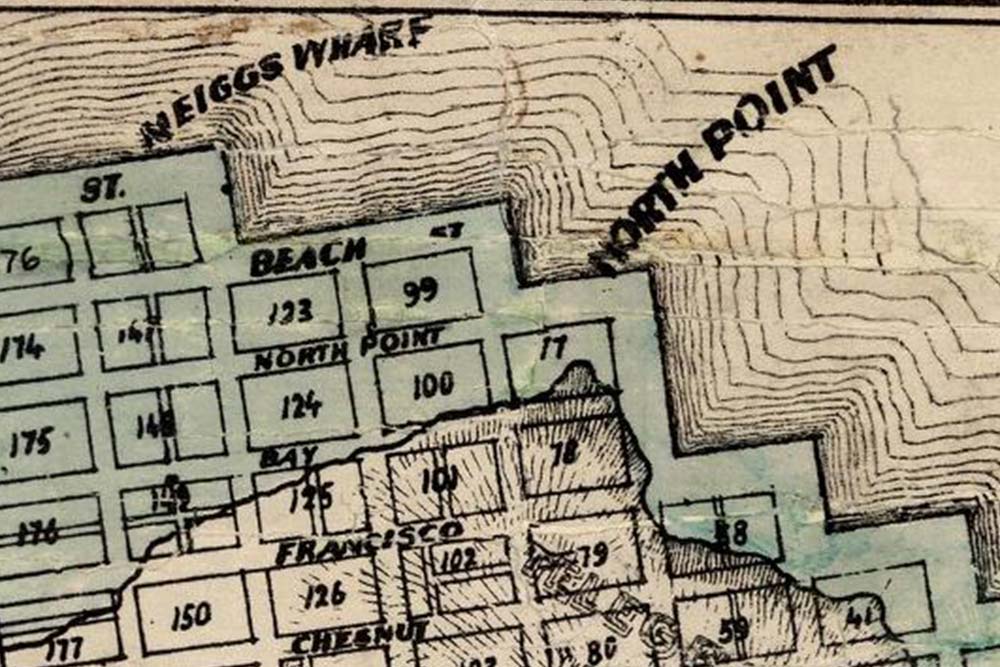

In name, folks often lump this flatlands area with Telegraph Hill, Fisherman’s Wharf, or North Beach, but it’s best described as North Point. Back when Bay Street was in the bay and Beach Street had a beach, a small cape poked north into what is now the center of a city block bounded by North Point, Bay, Grant, and Kearny Streets. This detail from an 1869 map shows the water lots around North Point awaiting their destiny as made land.

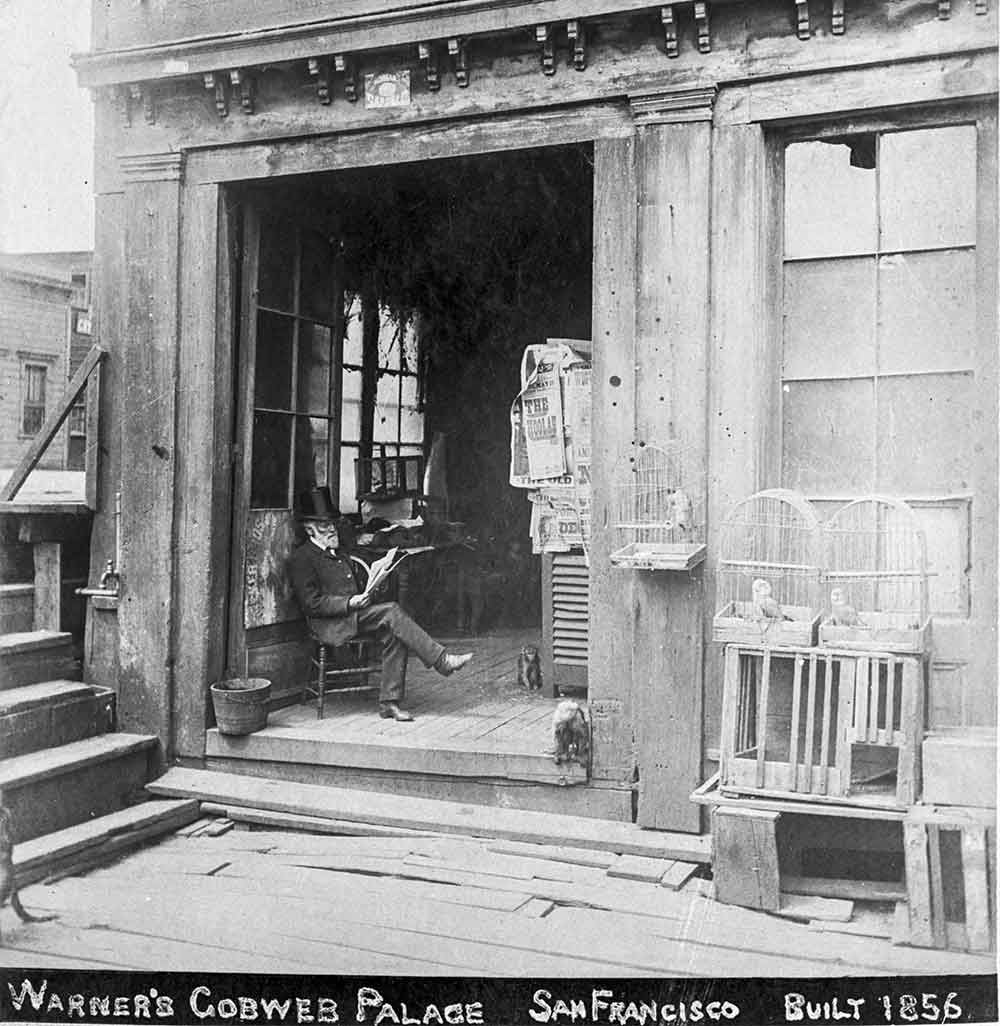

History-curious San Franciscans have long had at least a passing knowledge of the Cobweb Palace. Sometime in the middle of the 1850s, Warner took over what had originally been a boarding house/hotel at the base of the pier and made it a saloon and restaurant. This basic business morphed as Warner collected animals and curios and apparently offered a general amnesty to the city’s spider population.

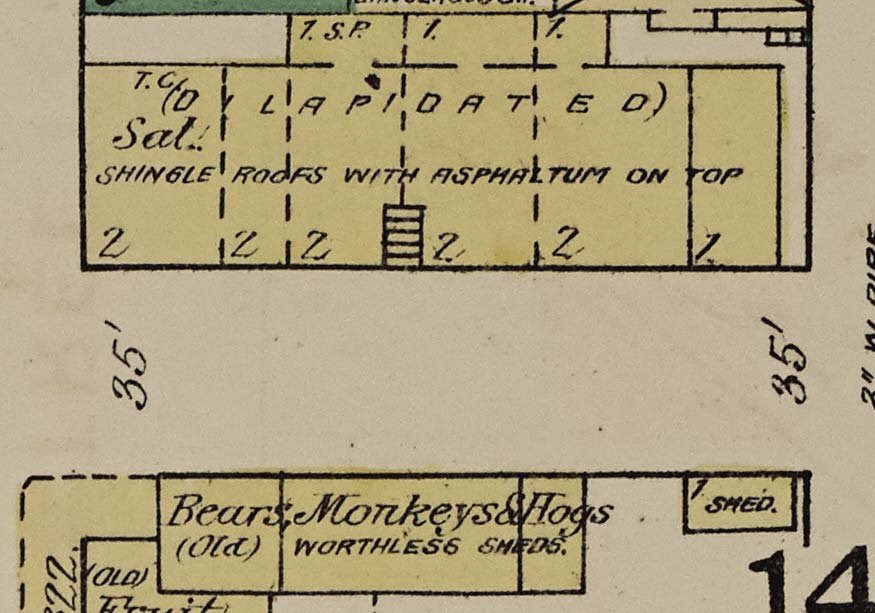

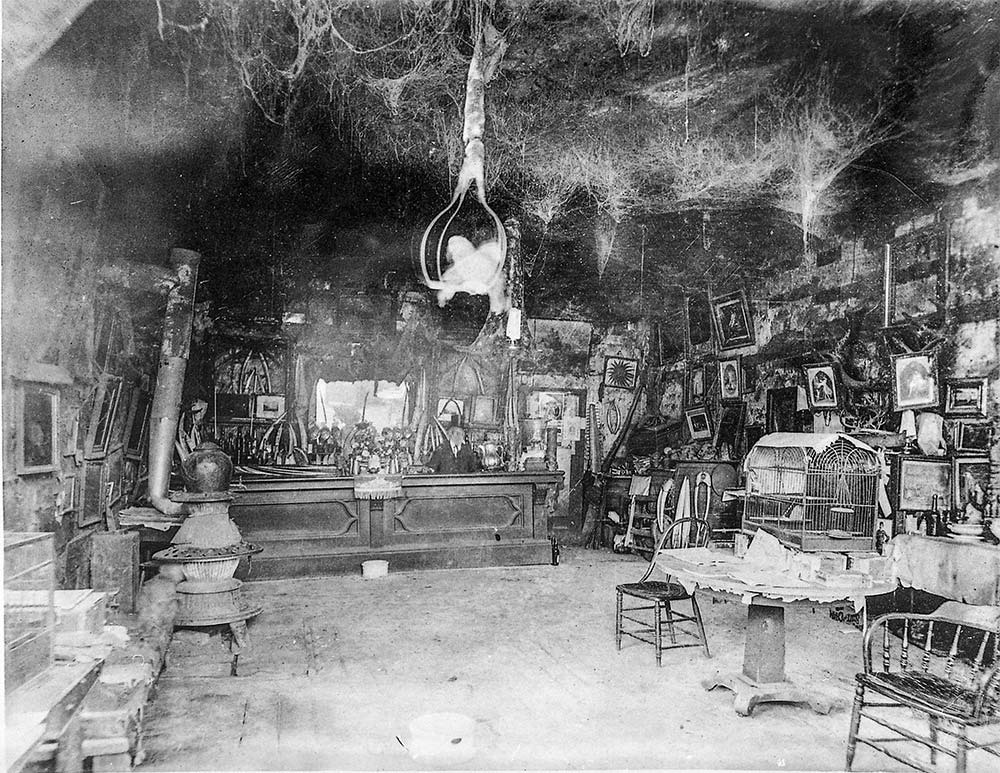

The bar became a one-man museum of old paintings, pianos, ivory tusks, seashells, coral, crab nets, spears, shark teeth, Polynesian carvings, obsolete and primitive weapons, and taxidermy. A shed opposite the bar served as an overflow zoo of bears, dogs, foxes, raccoons, badgers, pigs, and parrots.

If the Cobweb Palace operated today, the State of California would rescue the animals and post a warning sign to the arachnophobic and dust-allergic. Abe Warner owned a myna bird and a lemur, but not, it seems, a broom.

The Cobweb Palace, also called “Monkey Warner’s,” was a Sunday destination for locals. Children viewed the animals. Fathers bought clam chowder and a nickel beer from Abe. Buskers, musicians, and sideshow folk worked the wharf itself.

The end came in early 1893. A big storm had severely damaged the ramshackle sheds the previous December and the Cobweb complex was to be razed for a row of new houses. Warner’s curiosities and animals were auctioned off in June. The old host in the black top hat died three years later. The Cobweb Palace survived only in memories and a few great photographs published again and again in history books and looking-back newspaper columns.

Abe Warner's Cobweb Palace, circa 1886

— David Gallagher (@DavidGallagher) October 30, 2022

The Cobweb Palace (a saloon,1856-1893) sat at the foot of Meiggs Wharf on Francisco between Powell & Mason

I glaze over when I see these really old SF pictures, but I get interested when I can place them in a modern context. #sfhistory pic.twitter.com/bu9FnuXcTw

David Gallagher's recent examination and dating of the Cobweb Palace photos on Twitter.

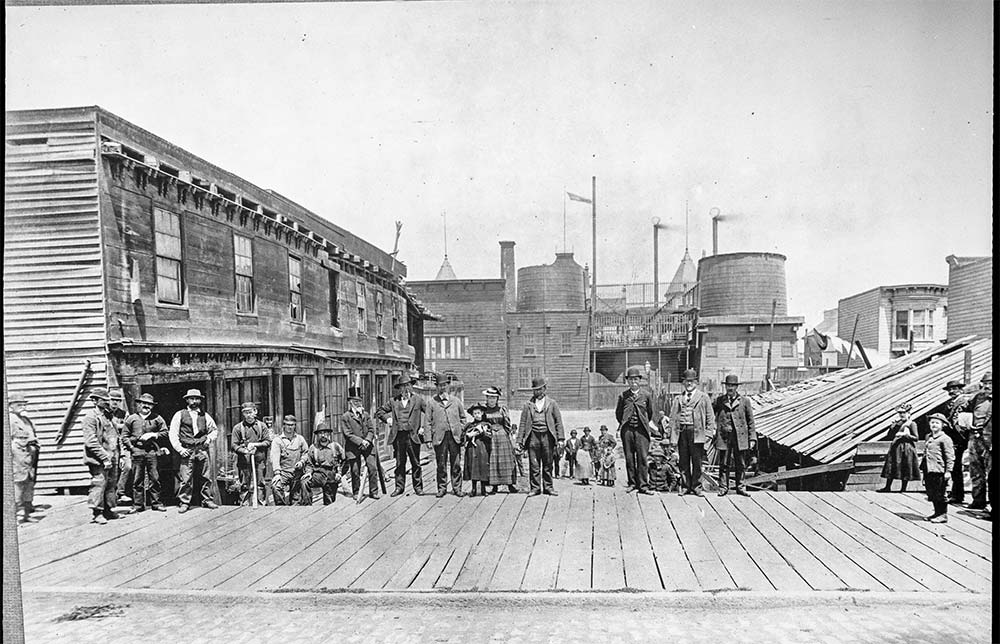

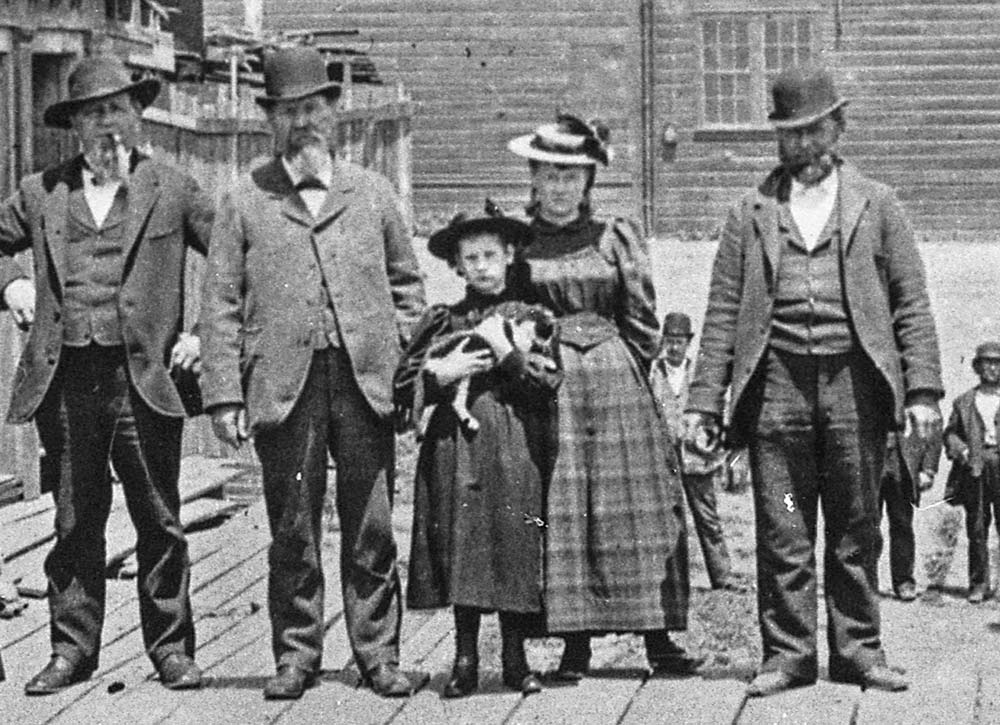

My friend David Gallagher, whose epitaph could already be written as “he looked at old pictures all day,” recently took a closer look at the extant images of the Cobweb Palace. He sussed out that they all likely came from one day shortly before the closing auction in 1893. One of his great deep-dive threads on Twitter picked out the presence of repeated characters visible in multiple shots, including the fan-favorite, “girl with cat.”

Twitter’s reputation as a garbage pit of vitriol, spite, and indignation is not undeserved. Twitter is a place where people who agree fight and snipe at each other about how they agree. But it is also the best social media platform for real-time open investigation and collaboration. Art Siegel (@arto) followed up on David’s thread and found an old newspaper article identifying Nathan Joseph, a “curio-dealer” living at 641 Clay Street, as the man who commissioned the original photographs.

A little more research in old papers revealed that in 1896 Mr. Joseph donated seven photographs of the Cobweb Palace to what is now the de Young Museum in Golden Gate Park. (The museum also supposedly owned a couple of Warner’s carved tusks.) From the park museum, copies were made and over time scattered to libraries, archives, and private collections.

I’ve seen dates put on these republished images ranging from the 1850s to the 1880s. Thanks to digitized resources and the existence of an online forum ideal for collaborative work, David and Art have now quickly and delightfully pinned down the time period to around May 1893.

Is this important? Perhaps not in comparison to Twitter’s role in public science, political reporting, and as a connective lifeline in times of disaster. But if the teetering platform fails in coming weeks such small satisfying local history wins and conversations will be what I miss the most.

Follow @DavidGallagher on Twitter and scroll through his great San Francisco history threads while you can!