The House Built on Sand

A 1904 DIY house built in the barren sand dunes of San Francisco's Sunset District still stands today.

But everyone who hears these words of mine and does not put them into practice is like a foolish man who built his house on sand. The rain came down, the streams rose, and the winds blew and beat against that house, and it fell with a great crash. (Matthew 7:26-27)

Jesus wasn’t talking about one Mr. Elbert N. Dodge.

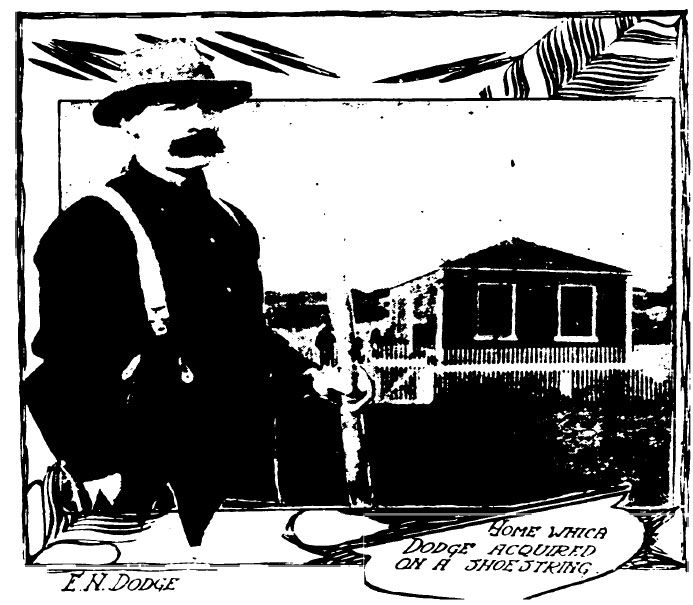

Dodge was featured in a San Francisco Chronicle article in January 1905 for buying a tract in the “forbidding and unoccupied” sand dunes of the Sunset District, building a house on the cheap, and supporting a family “in fair style but with little outlay of capital.”

One hundred and eighteen years later, the house that Dodge built over a year of Sundays and holidays still stands at 1549 22nd Avenue.

History-minded folks like myself have long admired the little house. Set back from the sidewalk, it presents itself as a quaint country cottage from the days before the assembly-line style of home building filled the dunes around it.

When Dodge arrived at the dawn of the twentieth century, most of the Sunset District still lacked graded streets, sidewalks, electricity, gas, sewage, or water mains. A house painter, he purchased four lots for $1,000 in August 1903. The full parcel was 50 feet wide and 240 feet long, running from 22nd Avenue west to the then-theoretical-23rd Avenue and lay in a hollow with a 12-foot high sand bank on its west side.

Dodge was a handy guy. With the help of his brother, he first constructed the 16-by-32-foot three-room domicile for himself, his wife, and two children.

Next came a barn and a chicken house soon to be occupied by 100 laying hens. Revenue from their daily production of eggs alone covered Dodge’s mortgage payment. (Dodge had put $40 down on the $1,000 purchase price for the four lots, paying $10 a month with a 6% interest rate).

A year after buying the sandy property the job seemed complete except for one problem: no water.

Pioneers to the cold desert of the Sunset District relied on a city water wagon that made periodic trips down the semi-graded 19th Avenue. Meeting the horse-drawn tank with buckets, washbasins, and jugs, the men and women then had to lug sloshing containers back over the dunes to their homes.

Dodge quickly tired of the trek and used a sand pump to dig his own well. Sixty feet down, he tapped the westside groundwater basin and erected a windmill to pump the liquid gold up into an elevated water tank.

That water, and a great amount of fertilizer, started an impressive little farm of cabbage, potatoes, beets, lettuce, turnips, cauliflower, onions, carrots, parsley, green peas, corn, parsnips, radishes, and rhubarb. In addition to the scores of vegetables, Dodge cultivated a strawberry patch of 350 vines. He planted fruit trees and bought a cow.

Ten years after purchasing the land, Dodge had a nice little ranch with garden plots and outbuildings. While three of the parcel lots were later gobbled up for individual houses in the late 1960s, the backyard of 1549 22nd Avenue still has a couple of small surviving structures.*

His industry and the obvious value he captured from “barren” sand dunes in one year is what made Dodge the subject of the 1905 Chronicle feature. The reporter couldn’t help but see him as a prescriptive example to renters:

Many people in this city living in houses they do not own could acquire homes by employing methods similar to those described. Those idlers who have plenty of time to watch the erecting of the big structures in San Francisco could get together, form some kind of a co-operative company, and buy some of these sand dunes cheaply on the installment plan. They could get credit to put up houses and barns, and raise chickens and ducks and grow berries and vegetables. A market would not have to be sought—it is here at the doors.

Perhaps it wasn’t a life for everyone, however. In contrast to the sober hard-working painter, Dodge had a neighbor, Annie Falix, who was allegedly “in the habit of burying herself in the sand near the beach and frightening little children.” When Dodge had her arrested for her odd behavior, the judge dismissed the case after giving the woman “a bit of sound advice.”

Woody Beer and Coffee Fund

*Researcher Jane Cryan thinks the cottage in the rear of the lot may be a relocated 1906 earthquake refugee “shack,” but it may just be a former farm building doing a clever impression.

Sources

Fred W. Schell, “How One Man Has Wrung Home and Income Out of a Bit of Sand in San Francisco,” San Francisco Chronicle, January 22, 1905, pg. 4.

“Woman Frightens Children,” San Francisco Call, July 26, 1905, pg. 10.