The Irving Institute

The scholastic past of a grand California Street apartment building.

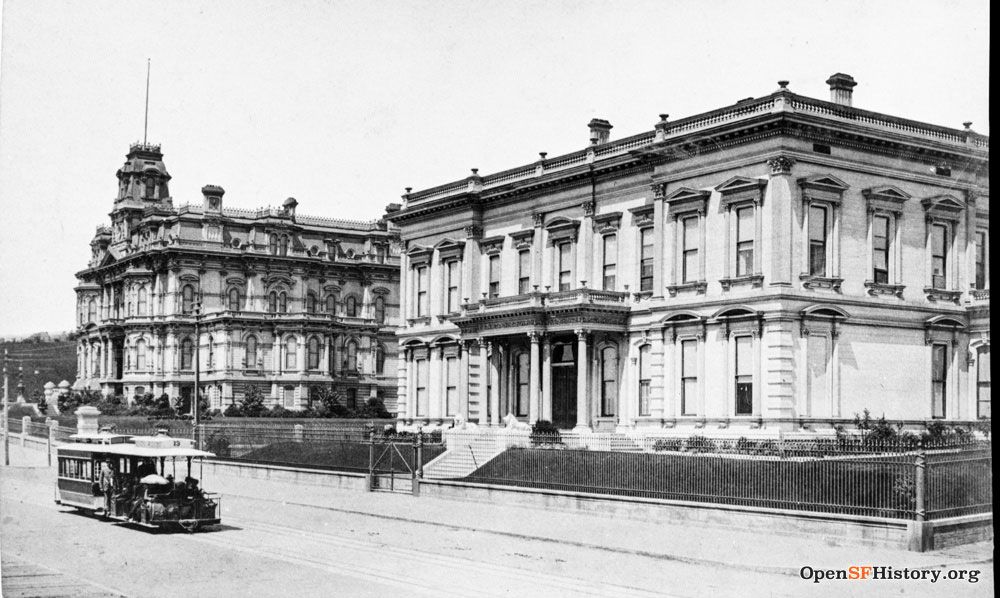

The mansions of the Big Four railroad barons on Nob Hill exemplified Gilded Age San Francisco. Elaborate, ridiculously over-done, block-filling, they were built to impress and intimidate more than be lived in. But the fires following the 1906 earthquake did a number on the summit, which now puts off more of an old-school-hotel fustiness rather than any aura of society balls and gas-lit intrigues.

The same California Street cable car line that opened up easy access to Nob Hill in 1878 also spurred development farther westward. Some great 1880s architecture survives beyond the 1906 fire line of Van Ness Avenue in the Western Addition.

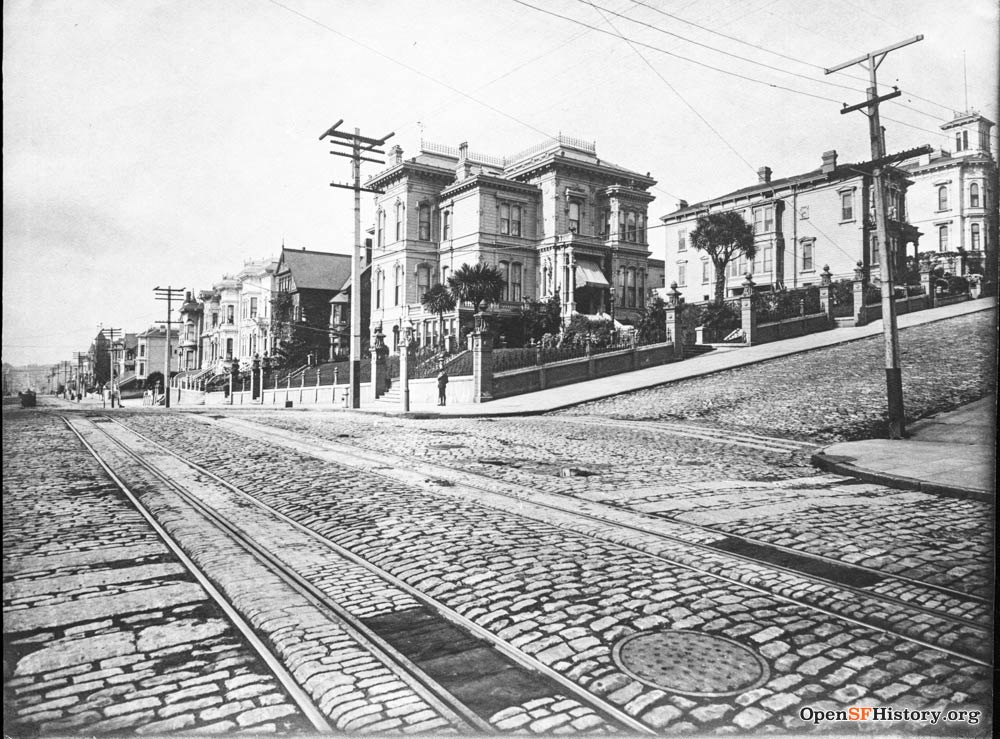

On parts of California Street past Franklin Street, it’s easier to capture that costume-drama feeling and imagine capitalists and society dames peering from their gingerbread-houses at cable cars clacking, clattering, and ding-dinging on cobblestone streets.

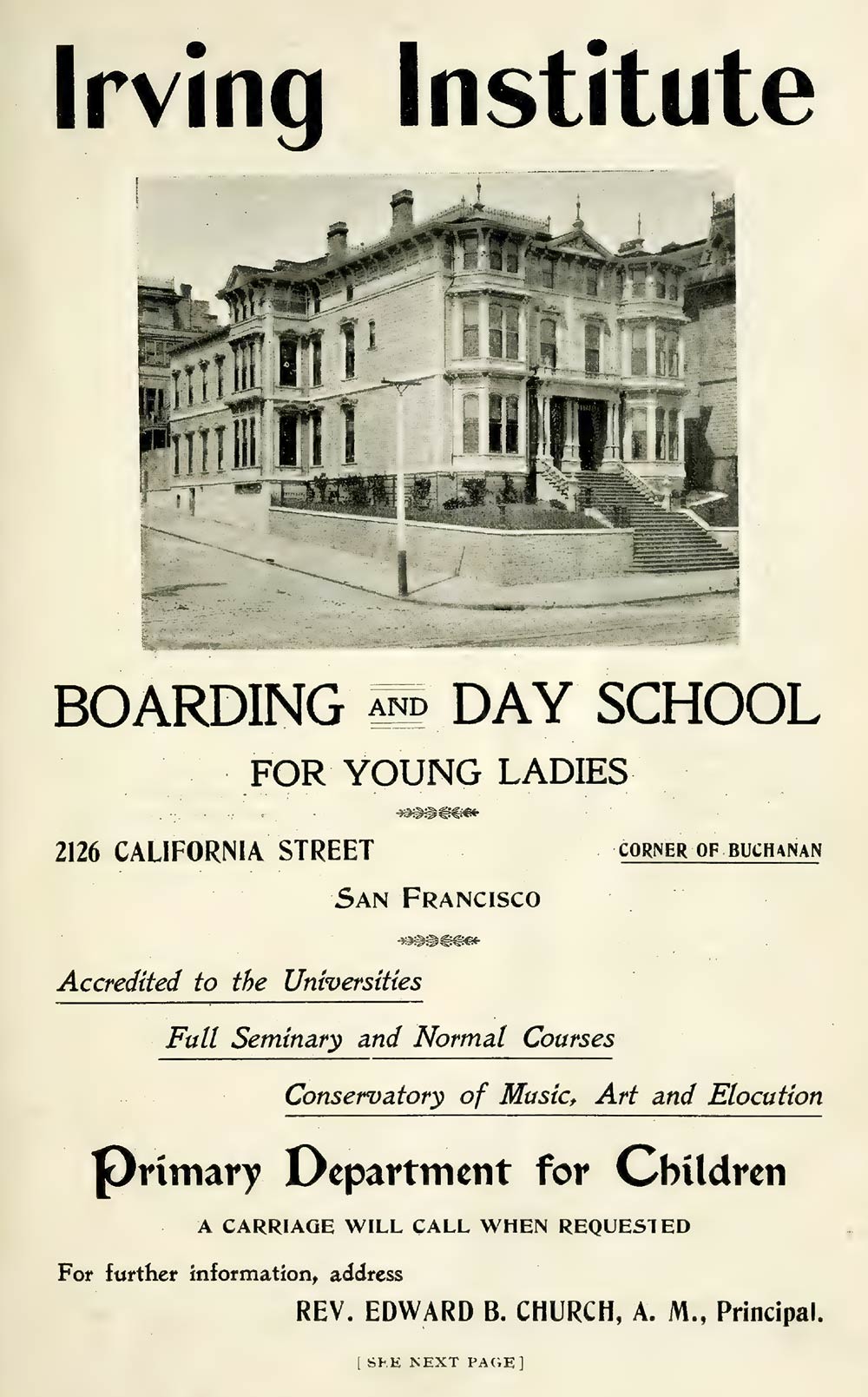

The circa 1881 multi-bayed, three-storied apartment building at 2186 California Street—originally a grand duplex addressed 2126 and 2128 California Street—is one of my favorites along this stretch. The Italiante-style ramble is set up and back from the northeast corner of Buchanan Street, on prominent view to the passerby.

Its occupants can easily return the favor: there are at least fifty windows on the front and side elevations. It is so on display, so memorable, that I recognized it immediately on a page of an old city directory.

In the 1880s and early 1890s, this block of California Street was the home of the well to do: merchants Zadoc Einstein and Joseph Bastheim, the family of W. H. Taylor, president of the Risdon Iron Works. There were servants. Neighbors advertised in the newspaper for a “competent coachman.” There were coming-out parties and lavish weddings.

But at the end of the 19th century, the fin-de-siecle, tides of fashion shifted and houses on the block began transitioning into apartment houses, seminaries, and schools. In 1898, the corner duplex of 2126-2128 California Street became Irving Institute.

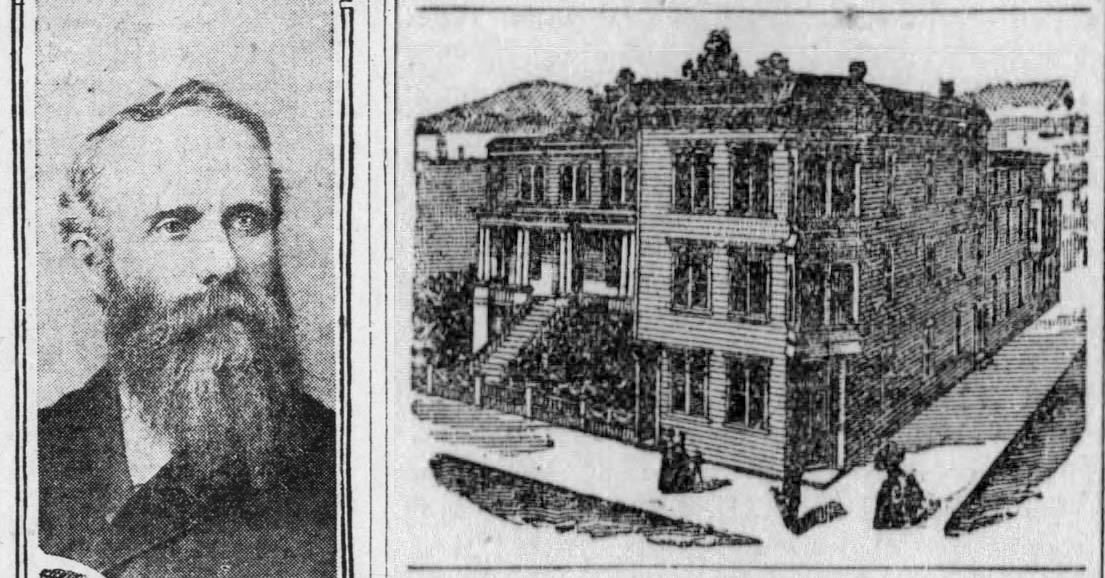

Reverend Edward Bently Church and his wife, Frances Kellogg Church first opened Irving Institute on Valencia Street in the late 1870s. The move from the Mission District to the “elegant and commodious mansion” on California Street was an ambitious step up for the young ladies’ academy.

At 1036 Valencia Street, the couple had 19 teachers on their payroll and could accommodate 50 boarding pupils in addition to running a day school. The relocation to California Street meant fewer boarders (30-girl capacity), but the neighborhood and building itself justified higher tuition rates.

While Italianate gingerbread had fallen out of style for the residences of the wealthy, it had an elegance perfect for a boarding school to impart long-established gentility and refinement. Edward and Frances certainly saw the building as a marketing asset, depicting it twice in their two-page directory ad.

Irving Institute was no mere finishing school where girls only learned how to talk nice and identify asparagus forks. There was an experimental laboratory and a library of more than 2,000 volumes. In an era when women were actively discouraged from seeking degrees, the school emphasized its accreditation and connections to East Coast women’s colleges. Supposedly, admittance to University of California or Stanford required no application, just the Reverend Church’s recommendation.

Irving Institute promised “symmetrical and harmonious development of the mental, moral and physical powers.” This meant literature, science, and the arts, especially painting and music. But for conservative parents worried about all this education, the students also received “cultivation of the refined and courteous graces of true womanhood.”

The school also ran a primary department for young children, including boys. A carriage was on call for pick-up and delivery of the small and privileged.

While we can’t assume the qualities of an institution based on its own fulsome marketing, Irving Institute seems to have been well respected. The school hosted annual alumni luncheons, had Stanford dean David Starr Jordan give commencement addresses, and tapped William Ford Nicols, Episcopal Bishop of California, to present its diplomas.

Church retired in 1902, “having been broken by overwork.” His wife, Frances, who was a dynamo—author, painter, saver of redwood forests—acted as the principal until her death in 1906. With the couple gone, Irving Institute went into decline. Enrollment dropped. The California Conservatory of Music moved in to share space (and presumably the rent). The school moved to smaller quarters at 147 Presidio Avenue in 1909, and lasted only another ten years.

The commodious two flats of 2126-2128 California Street were re-addressed as 2186 California and the structure divided into 22 apartment units, their income likely assisting the building's survival when so many neighboring houses were demolished in the 1920s and 1930s.

Now there’s one mystery left for me: who was Irving?

Send me your guesses, theories, or researched conclusions.

Woody Beer and Coffee Fund