The Monkey Block

How San Francisco's Montgomery Block, built in 1853, survived every disaster, but lost to one man.

“The march of time, as a general rule, takes a heavy yearly toll of the works of man. Once in a while one of these is built so sturdily that it defies the ravages of the elements and the demands of progress, and is left standing as a landmark, to help record the passing of the years.”

Or not, as we shall see.

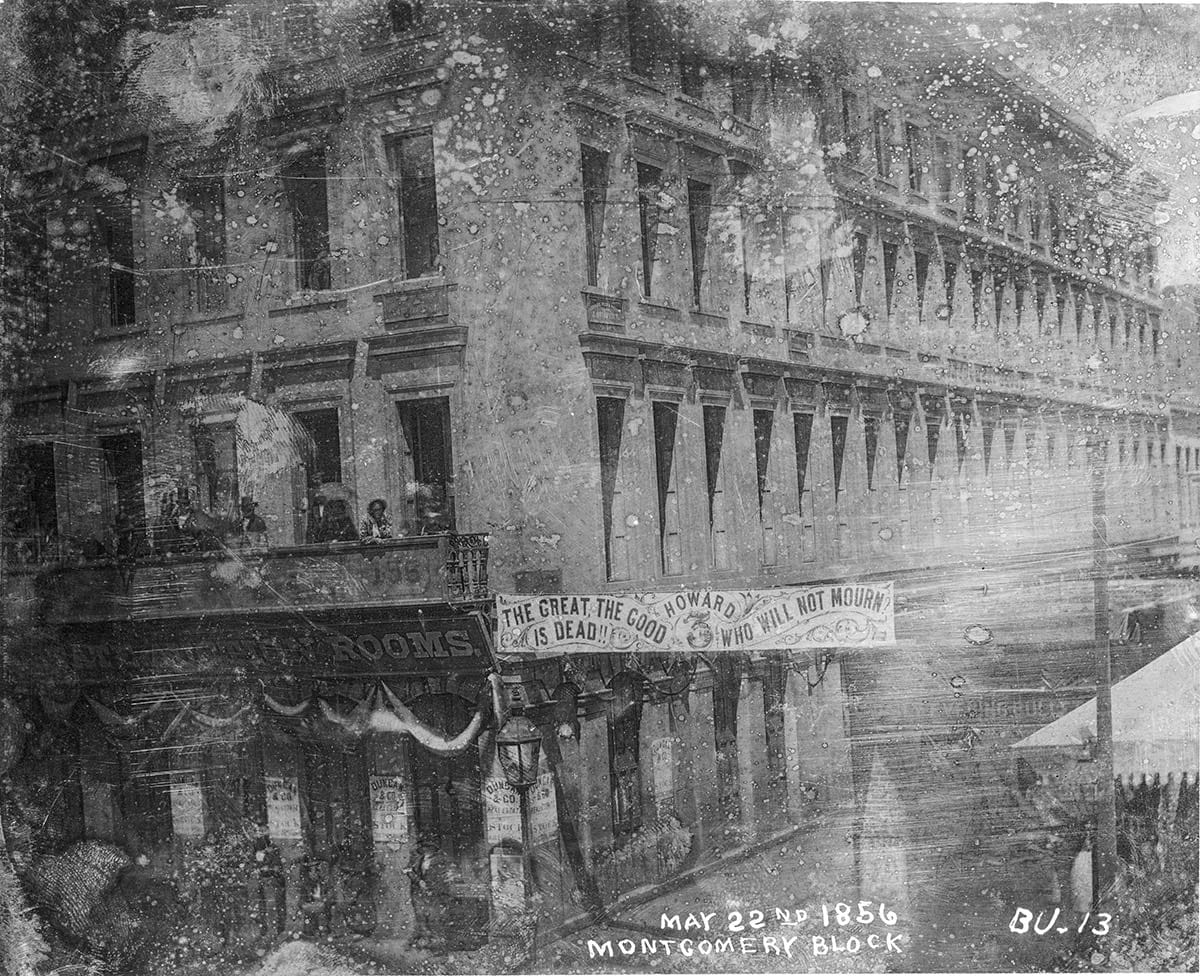

George Tays wrote the above words in 1936 about San Francisco’s Montgomery Block, an office building constructed in 1853 at the southeast corner of Washington and Montgomery Streets.

Outside of Mission Dolores, the building was perhaps the most significant survivor of San Francisco’s early days. Occupied over its life by bankers, lawyers, journalists, civic leaders, writers, painters, poets, herbalists, sundry merchants, spaghetti sellers, and purveyors of pisco punch, its thick walls were saturated with history. It was designated California State Landmark #80 in 1933.

Then, in 1959, it was gone.

Today, a corner of the Transamerica Pyramid, the modern icon of San Francisco, stands in its place.

Does the path from A to B have a lesson for today? Perhaps. Perhaps not.

The Best of the West

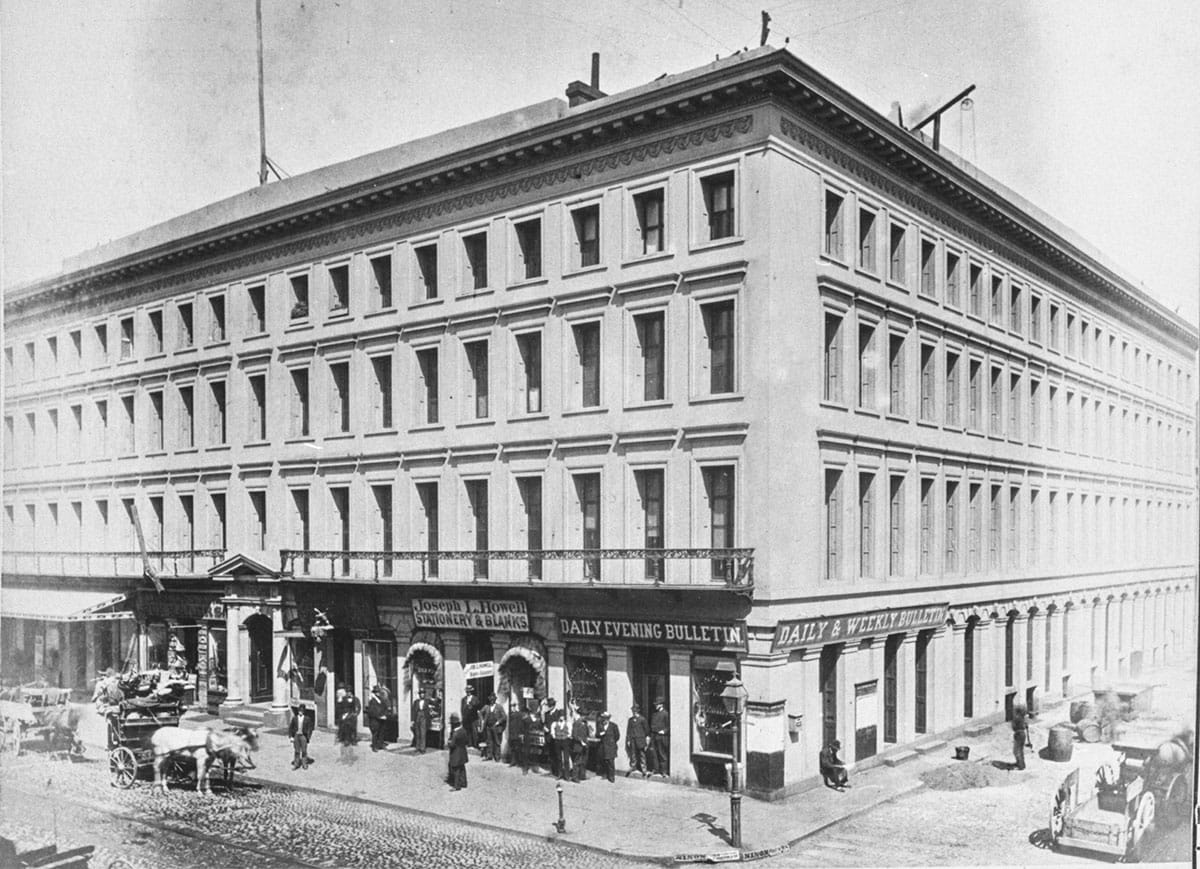

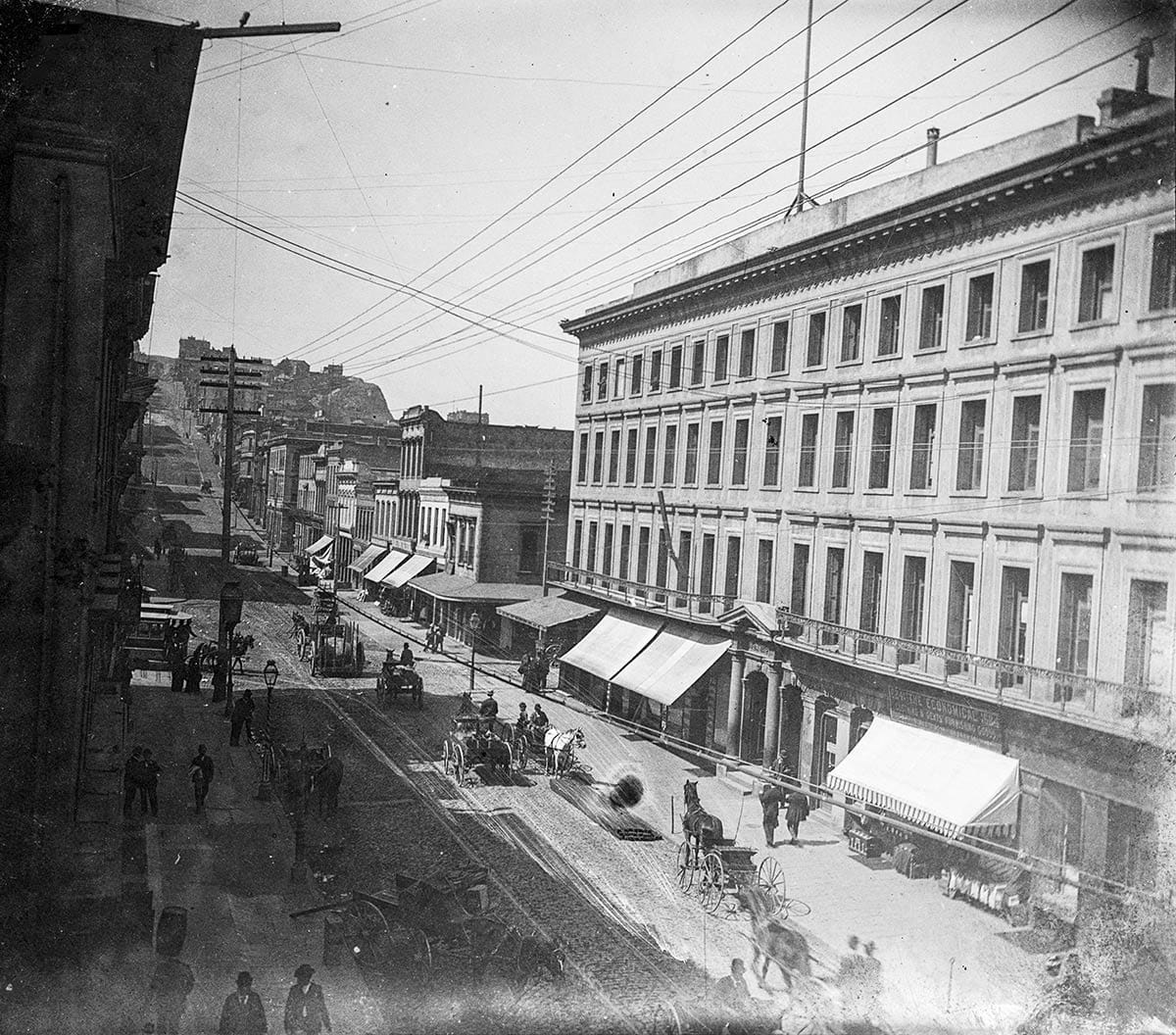

In the early 1850s San Francisco caught on fire every year, sometimes twice a year. Henry Halleck’s law firm made a bold attempt to overcome the young town’s incendiary inclinations by erecting a four-story (with basement) iron-framed office building with three-foot-thick walls and iron shutters. At the time, it was the largest in the American west.

The building was a business proposition, not a work of art, but Halleck’s architect, Gordon Cummings, added some Classical design elements: a Roman portico around the main entryway topped by a relief of George Washington’s head; a decorative frieze along the cornice; and a second-story ornamental balcony.

Above the ground-floor arches were gargoyle faces in relief, each looking like an earnest capitalist of the 1850s, but supposedly meant to represent luminaries of western civilization and exploration. Some of these famous men would not be lauded today (Christopher Columbus, Hernando Cortez), while others we mostly keep on the heroes’ roll: Benjamin Franklin, Shakespeare, etc.

The Montgomery Block did take up a whole block: Montgomery to Sansome, Washington to Merchant Street. (That block of Merchant was later sacrificed to build the pyramid.) Water was piped in from an artesian well in the courtyard.

The advertised resilience of the building was repeatedly tested. It survived big fires (and explosions) of the 1850s and 1860s, the 1868 earthquake, and then, miraculously, both the 1906 earthquake and the following firestorm which incinerated its neighbors.

It also survived economic vicissitudes. When the newspapermen, lawyers, bankers, and mining speculators shifted to more fashionable quarters down the street the Montgomery Block kept rolling along with humbler and more interesting tenants.

A large billiard parlor occupied the upper floors in the early days. By the end of the 19th century, that space held about half of Adolph Sutro’s massive personal library, some 250,00 volumes and many exceedingly rare.

The ground floor housed famous bars (The Bank Exchange, where Pisco Punch was made popular) and restaurants (Coppa’s, where 1890 artists created an early and maybe more fun San Francisco version of New York’s Algonquin Table).

Two generations of San Francisco’s arts community made a home in the Montgomery Block. Name any writer, poet, or painter associated with or visiting the city between the 1870s and the 1940s—Mark Twain, Emma Goldman, Jack London, Ambrose Bierce, Mary Austin, Gelett Burgess, Xavier Martinez, Dorothea Lange, Maynard Dixon, Frida Kahlo, Otis Oldfield, Kathleen Norris, Ralph Stackpole—and you will invoke someone who walked its halls, worked in its windows, ate, and probably drank too much, at its tables.

Constructed pre-light-bulb, when big windows were necessary in offices, the building had 16 windows spanning each story of its front facade, 20 along its sides, and a center court bringing light into its center: perfect for the artists who set up their studios inside when the financiers, lawyers, and insurers moved out.

Survivor

After surviving the 1906 earthquake, the Montgomery Block’s ground-floor iron shutters saved it from the ensuing firestorm, although blazes erupting at the cornice needed to be put down several times. Its resilience made a shield for the blocks just north, preserving much of the Jackson Square neighborhood.

One of the great stories in the aftermath of the 1906 disaster was the preservation of much of Adolph Sutro’s library. (Part of the collection stored at a Battery Street warehouse were lost to the flames.) The extensive library of the San Francisco Microscopical Society (still around!) was also preserved in the Montgomery Block when every other major collection of books in the city was lost.

(I remember reading somewhere that library staff began moving Sutro’s library from the Montgomery Block as the fires approached from the south. Ironically the “safer” location burned while the Montgomery Block survived. Did I imagine this story? Someone else know this tale?)

The damage from the quake and fire was relatively minor in the end: a few of conquistador and statesmen heads fell off. Others were removed and sent to the collection of the de Young Museum as historical relics. (It is unlikely the de Young still has these in its collection, and if they do, they likely do not know it.)

Monkey Business

It was in the 1930s that occupant artists living off Works Progress Administration. funding nicknamed the old building the “Monkey Block.” They may have been up to some monkeyshines while painting the Coit Tower murals and other art installations around the city.

The name stuck and in most newspaper articles after World War II the building gets called the Monkey Block as much as the Montgomery Block.

The state historical landmark plaque affixed in 1933 recorded some of the structure’s important history and concluded “The building is preserved in memory of those who lived and worked in it.”

But memory-preservation was relatively short.

Post-World War II, when redevelopment and freeways were all the rage, government and business leaders maintained that the only way San Francisco’s downtown could survive economically was with more parking.

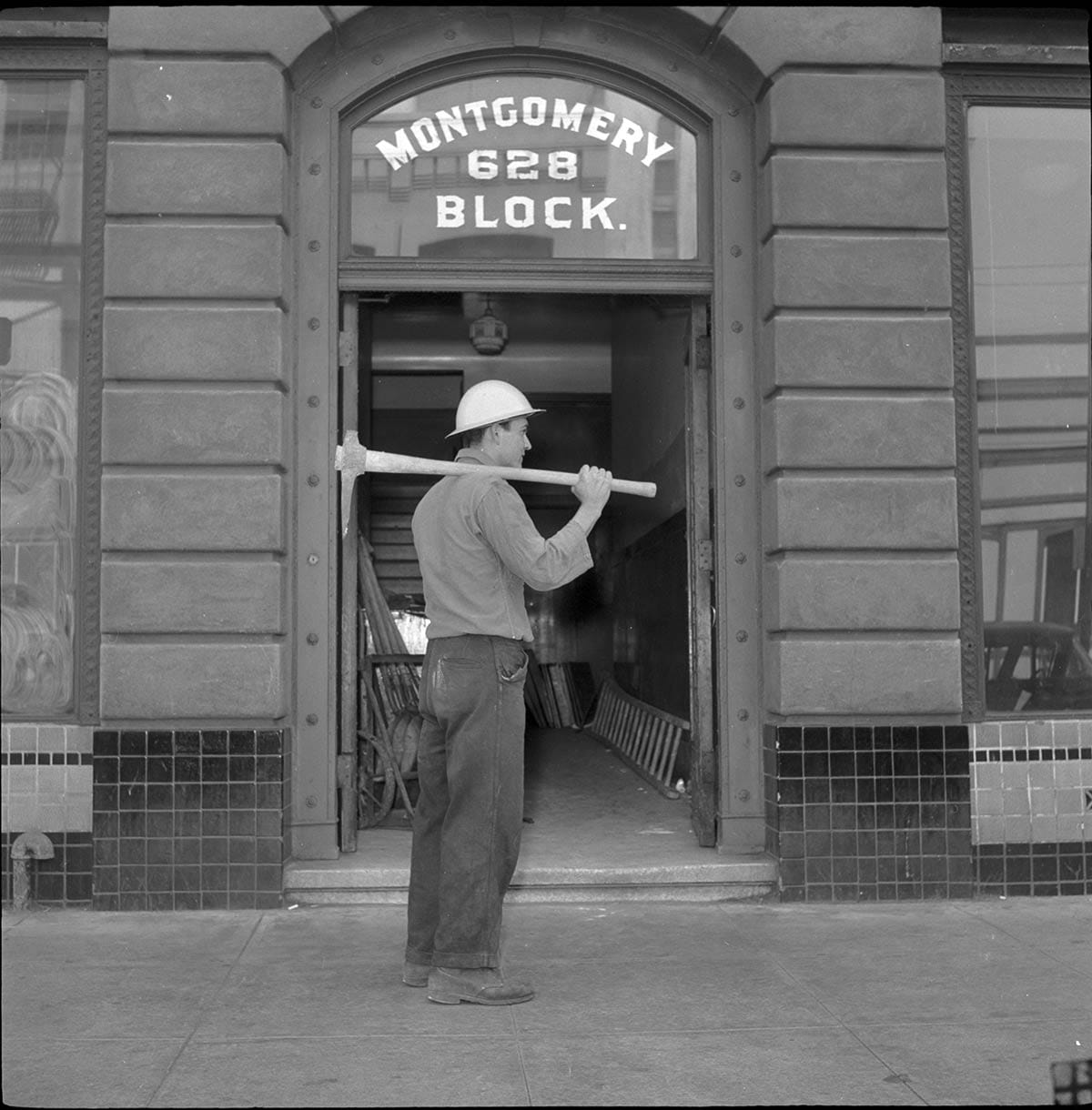

Garage magnate and “parking tycoon” S. E. Onorato was happy to help. He tore down the Montgomery Block in May 1959 for a parking lot—not a garage, just a rectangular asphalt lot with white lines. A dozen of the remaining gargoyles were saved in the demo and offered for $50 apiece. A couple ended up in a KQED fundraising auction.

A few years later a 16-story parking garage was in the works for the site, but then a better offer came along.

The economy was stagnating. City and business leaders maintained that the only way San Francisco’s downtown could survive economically was to attract big financial services and insurance companies and construct corporate towers. A controversial “Manhattanization” of the financial district began.

In January 1969, with the Bank of America building rising at California and Montgomery Streets to become the city’s tallest building, the news got out that the Transamerica Corporation was shooting higher on the site of the old Monkey Block: a 1,000-foot-tall pyramid of high-end office space.

And so it happened, not to everyone’s delight.

Earlier this year the Transamerica Building celebrated its 50th anniversary, now hailed as an architectural icon, a symbol of San Francisco. Some of the speakers made reference to the current economic difficulties in San Francisco’s downtown.

City and business leaders now say we can’t depend on offices anymore, that we need to diversify downtown for it to survive economically.

Most suggest we need to find ways to attract artists to the area.

Woody Beer and Coffee Fund

My old friend Lorri Ungaretti will be giving a two-hour mini-course on the history of the Montgomery Block on Thursday, January 16, 2025, from 1:30 to 3:30 pm at 160 Spear Street in San Francisco. The mini course is sponsored by OLLI (Osher Lifelong Learning Institute) and the fee is $29. If you are interested, send an email to olli@sfsu.edu!

Oh, and if you want to have a coffee or a beer sometime, I am so up for that! Thanks to Vincent C. (F.O.W.), Athena K., Phillip S., and Lance L. for their recent contributions to the good cheer fund!

Sources

“Soldiers and Clerks Save Custom House,” San Francisco Chronicle, May 7, 1906, pg. 11.

“Move Books to Place of Safety,” San Francisco Chronicle, May 23, 1906, pg. 3.

Edward A. Morphy, “San Francisco Thoroughfares,” San Francisco Chronicle, May 18, 1919, pg. 6.

George Tays, “The Montgomery Block,” California Historical Landmarks Series, State of California, 1936.

“No Garage at Monkey Block Site,” San Francisco Chronicle, February 12, 1960, pg. 1.

Donald Canter, “1040-Foot Skyscraper for City,” San Francisco Chronicle, January 26, 1969, pg. 1

Harvey Smith, “The New Deal Artists of the Monkey Block,” Living New Deal website, March 30, 2021.

“Meet the Monkey Block,” San Francisco Historical Society website.