The Unkindest Cut

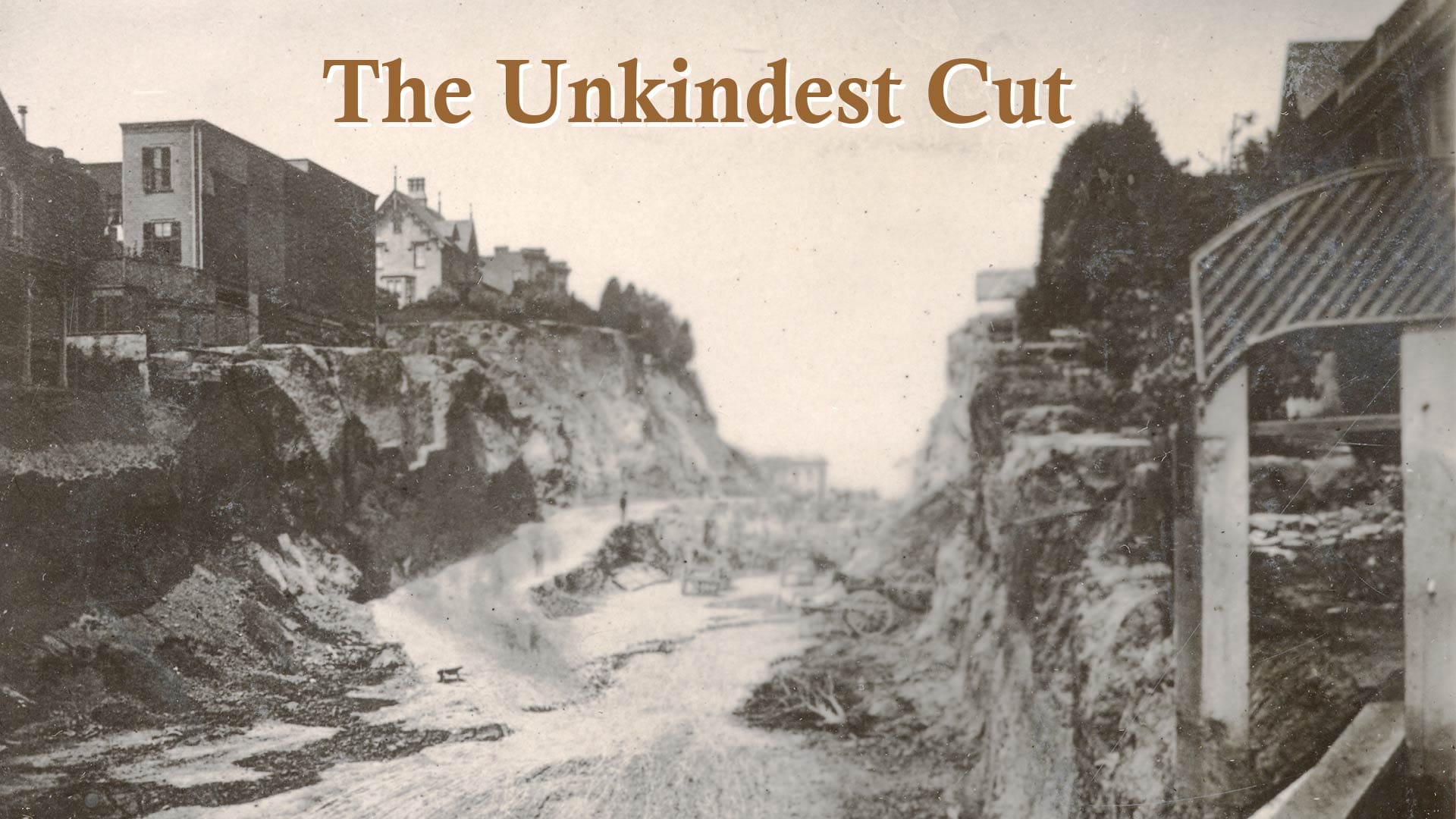

The 1860s Rincon Hill project that put the cut in San Francisco's East Cut neighborhood.

Happy New Year’s Day and thanks for being here.

For my own special, and perhaps selfish, reasons, I am excited and optimistic for 2025. I know it’s not that way for everyone this year. But we start with hope and we put in the work, and we try to stick together, right?

Today is a day for resolutions and for planning. In San Francisco we have a new mayor and a lot of new supervisors who I’m sure are ready to roll out their visions for the city. The last election’s results somewhat demonstrated a desire for change. Candidates made big promises with big ideas.

Not to kill the vibe, but this week’s story is about an elected official’s big idea that ended up being pretty terrible.

The Hill That Was

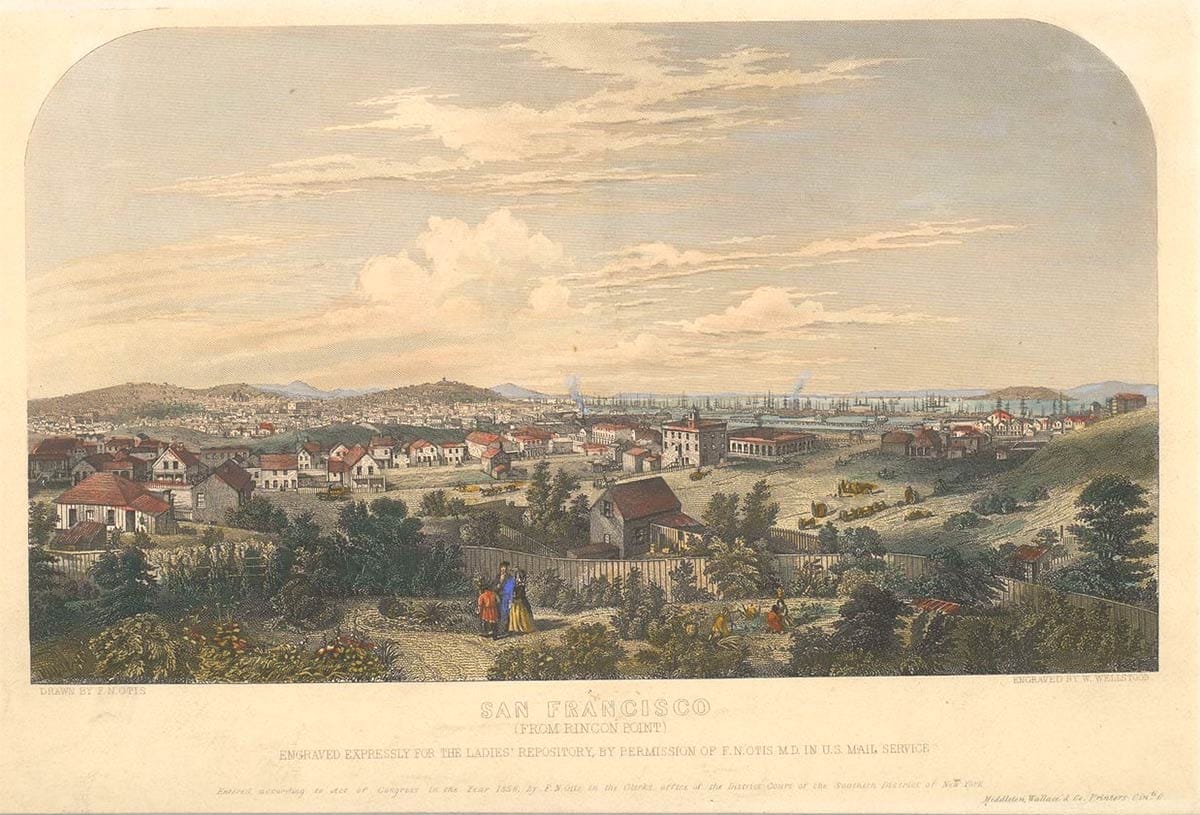

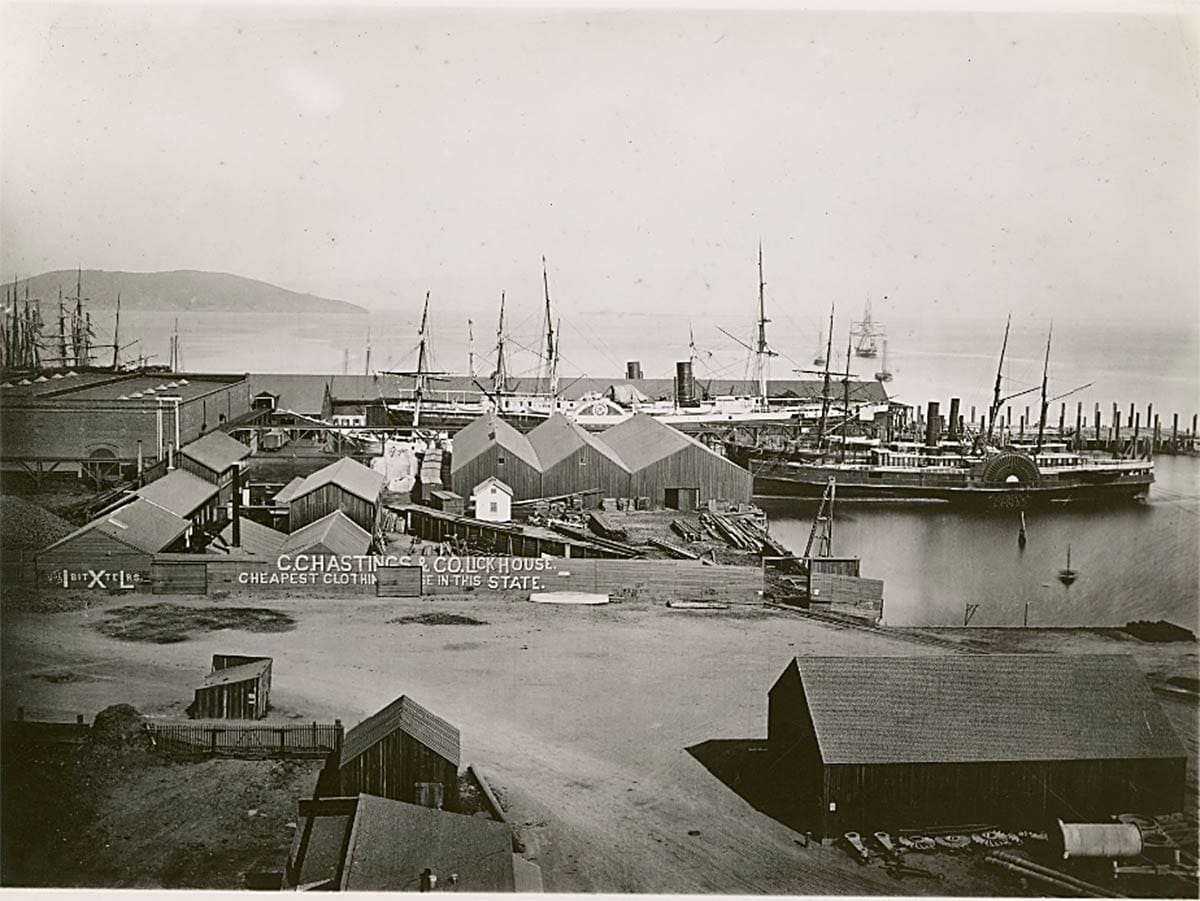

Before the Gold Rush, San Francisco was a small pueblo set on a cove bracketed by Telegraph Hill on its north and a shorter prominence on its south, Rincon Hill. The 120-foot peak of Rincon eased down into a jut of land separating Yerba Buena Cove from Mission Bay to the south. (Read more about the vanished bay that gave that neighborhood its name.)

Yerba Buena Cove was filled in quickly with sand to make our present-day downtown. Despite more than a few 1850s proposals to raze it, Telegraph Hill is still with us.

What is left of Rincon Hill sits under the western anchorage of the Bay Bridge.

For most of my lifetime Rincon Hill meant warehouses, light industrial buildings, and freeway access ramps. But in the 1850s and 1860s, Rincon Hill meant money and polite society. It was the enclave of the San Francisco gentry.

The Most Elegant Part of the City

In Spanish, rincón designates an inside corner and was used to describe angles of area formed by hills or woods or water. In San Francisco’s first two decades, Rincon Hill was the corner for the city’s elite.

With relative shelter from winds, warmer temperatures, and a good prospect of the bay and growing city, the gently rising hill was San Francisco’s first desirable neighborhood.

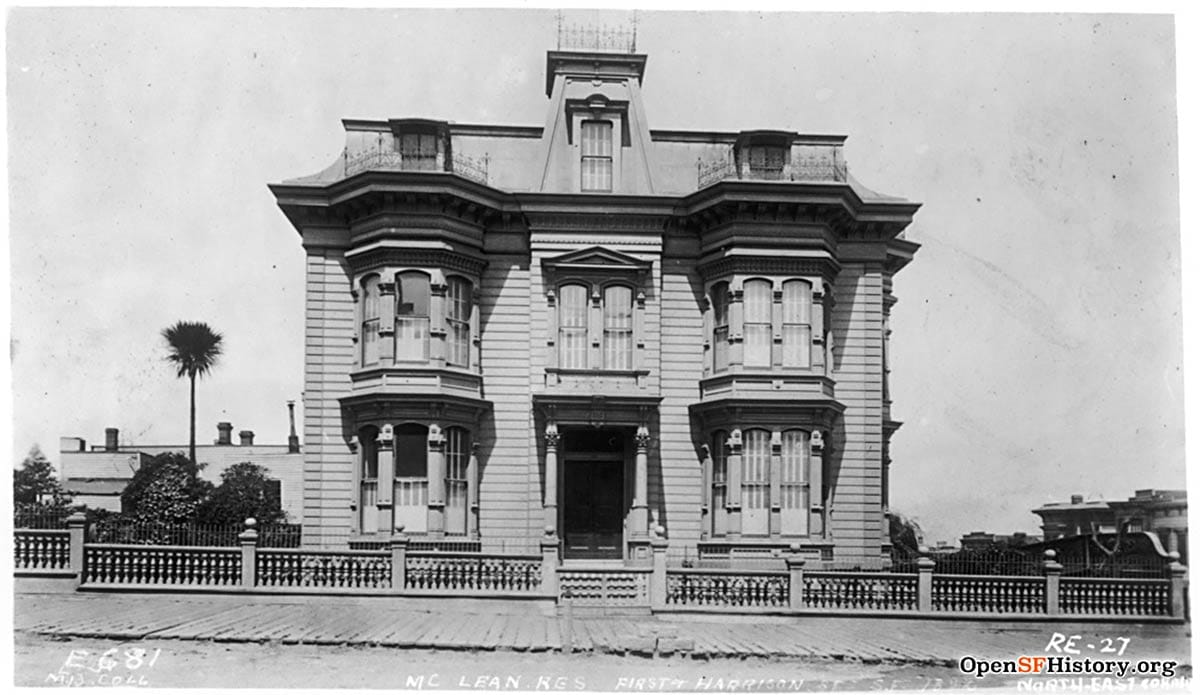

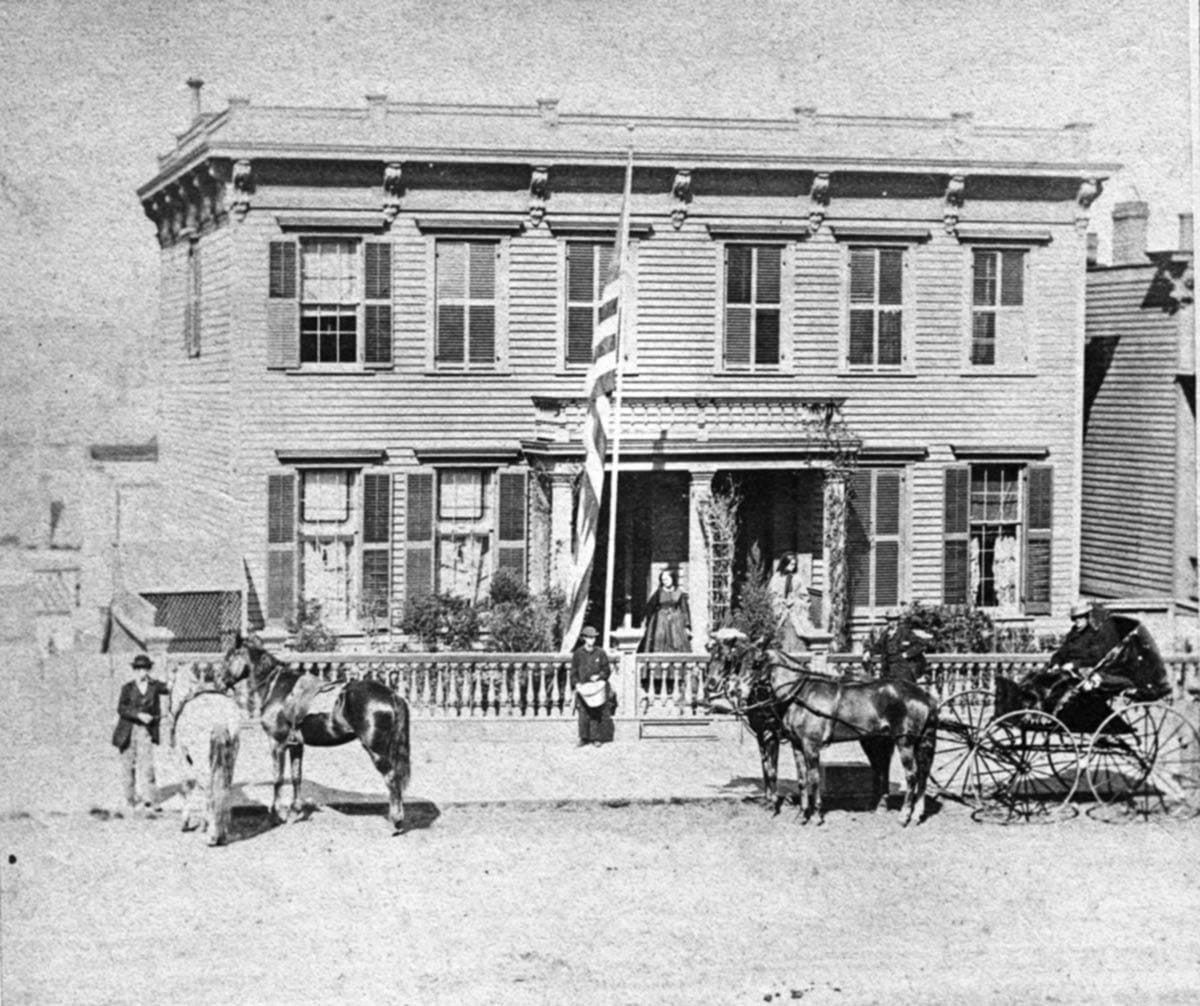

Affluent merchants, bankers, manufacturers, and clergymen dotted the slope and hilltop with gothic towers, mansard roofs, and ornamental fences.

Their residential gardens were the best in the city. Consuls, countesses, senators, and mayors all lived on Rincon Hill, which was described in 1861 as “unquestionably the most elegant part of the City.”

But then a member of the state legislature had a big idea.

The Second Street Cut

There wasn’t a problem to solve, really.

John Middleton had been a mover and shaker in San Francisco’s politics from the town’s inception and was the city’s most prominent real estate auctioneer. He was the one who came up with a big idea.

Namely, if 2nd Street between Howard and Bryant streets was cut down to a manageable grade for large wagon teams, that direct connection between downtown and the Pacific Mail wharves on the other side of Rincon Hill would radically increase property values along the street.

There was also a presumption that the transcontinental railroad would ultimately terminate at Mission Bay, adding to the attractiveness of 2nd Street as a thoroughfare from the bay to the city center. Oh, and minor point: Middleton owned property on the south side of the hill on 2nd Street.

It was Progress. Everyone would prosper. Huzzah.

In 1867, Middleton ran for state assembly and won. In early 1868, he introduced a bill authorizing the 2nd Street cut. It passed the legislature and the San Francisco Board of Supervisors were directed to start digging in 30 days.

How did the wealthy Rincon Hill folks feel about a 50-to-70-foot channel chopped out of their neighborhood’s most prestigious block? They were not happy.

A writer to the Daily Alta dismissed their NIMBY grumblings: “a very few influential people [should not stop] the march of improvement.”

Obviously, the Rincon Hillers weren’t that influential because despite their protests, and some initial inaction by the Board of the Supervisors, in early 1869 the state Supreme Court ordered that 2nd Street be cut just as the legislature directed. Work began.

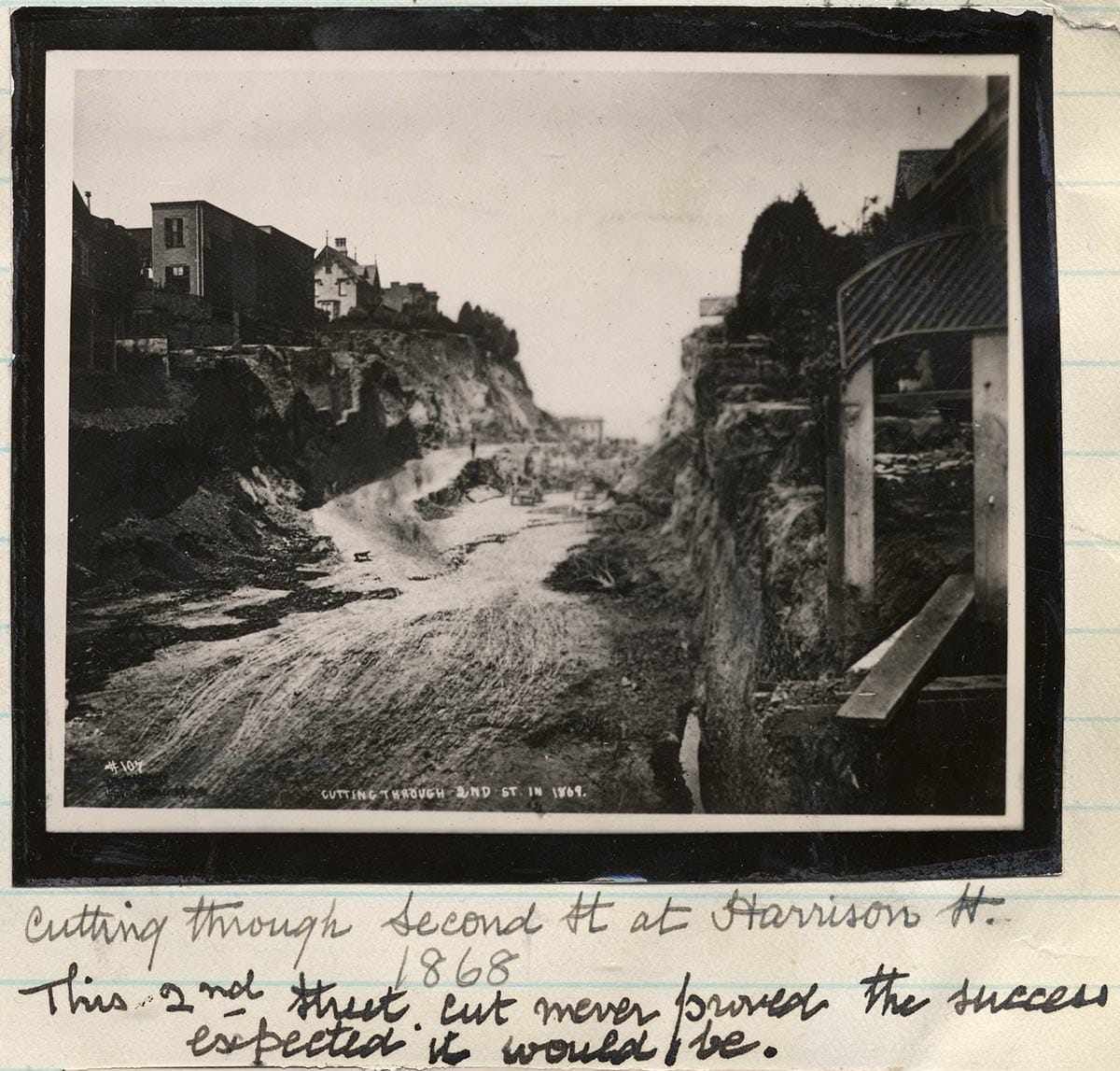

It was not pretty.

New mayor, Thomas Selby (who lived on Rincon Hill), was among the unhappy, believing that the cut and the bridge needed to run over the Harrison Street gash cost way too much, benefited just a few speculators, and was “a public outrage.” Plus, the state poking its nose into local matters with a special law for San Francisco to rip up a hill and destroy people’s homes was “destructive of legislative integrity.”

But the judges, newspapers, and state legislators all said relax. Property values will go up. Everyone will prosper. Huzzah.

It did not work out that way.

Many Had to Pay

Rincon Hill is pretty solid, but the giant slice out of its middle was immediately a notorious mud-river on rainy days. Slurry from the sides collapsed a rickety street-to-heights staircase multiple times. Some of the finest houses in the city were condemned and others clung precariously to the edge of the new ravine.

The best story: a visiting parson tried to locate the home of the Episcopal bishop of California, William Kip, who lived at 338 2nd Street.

“So I went to 2nd Street and I found in the part where his house ought to have been a fresh-made cliff, 50 feet high, on either side, and a crowd of navvies carting away stuff. It was impossible to reach the Bishop’s house from the street, so I beat round to get to the back of it. On arriving at the spot I asked where the Bishop lived. ‘The Bishop?’ said a jolly-looking gentlemen to me; ‘why his house tumbled down into the street.’”

(The Bishop had moved to Franklin and Eddy Streets.)

Hoodlums up on the cliffsides routinely pelted pedestrians below. The writer Charles Warren Stoddard (who lived on Rincon Hill at the time) recorded that it was dangerous to walk through the gap at night “without a revolver in one’s hand.” People complained over the expensive and the crude Harrison Street bridge. Stoddard called it “an agony of wood and iron, the most unlovely object in the city.”

So the 2nd Street Cut was ugly and muddy and dangerous...at least property values went up, right? Commerce must have flooded to 2nd Street?

Nope. The wagons mostly continued using 3rd Street and other routes. Home values dropped precipitously. Everyone was mad.

Here’s historian John S. Hittell in the 1870s:

“Rincon Hill has lost much of its beauty and all of its preeminence as a district for fashionable dwellings; the most active advocates of the scheme made nothing by it; and the direct expenses of this improvement was three hundred and eighty-five thousand dollars [something like $9 million in 2025 dollars], while the loss to citizens beyond all benefits was not less than one million dollars. Many had to pay for the errors of judgement committed by a few.”

Oh well.

Celebrating the Cut

The fires following the 1906 earthquake cleared Rincon Hill, both the good and the bad of it. The 1930s Bay Bridge construction pretty much obliterated the rest of the hilltop. If you walk from downtown to a Giants game, you may not or may not notice the slight rise on 2nd Street.

This century, however, the wealthy and fashionable have somewhat returned. Lots of condo towers have gone up (and some affordable housing), and the mostly inaccurate name of Rincon Hill (No corner! No hill!) has been supplanted by new historically themed branding.

Enjoy browsing some of the housing options in “The East Cut,” and encourage your elected officials to be judicious with their next big idea.

Woody Beer and Coffee Fund

Keep your eyes open, as I am working on a schedule of 2025 San Francisco Story events. Should have some dates next week! My great thanks to Linda G. (F.O.W.), Jim B. (welcome Jim!), John A. (F.O.W.), Todd W. (F.O.W.), Canice F. (F.O.W.), and Luba M. (Super F.O.W!) for their generous donations to the keep-Woody-social (by having beverages with people) fund. Our mugs doth overflow.

Let me know when you are free for a beverage. We have to spend some of this cash!

Sources

The late Albert Shumate is the go-to for early Rincon Hill history. You can probably track down a copy of his Rincon Hill and South Park (Sausalito: Windgate Press, 1988). It may have been my favorite San Francisco history book published in the 1980s. Harder to find are:

Albert Shumate, A Visit to Rincon Hill and South Park (San Francisco: Yerba Buena Chapter of E Clampus Vitus, 1963)

Albert Shumate, The Early Gardens of Rincon Hill (San Francisco: The Arion Press, 1990)

Albert Shumate, “Rincon Hill or Telegraph Hill: Robert Louis Stevenson’s Introduction to the South Seas,” California Historical Society Quarterly, Vol. 46, No. 3, September 1967, pgs. 223–234.

“Rincon Hill Grade,” Daily Alta California, April 26, 1868, pg. 1.

Reverend Harry Jones, To San Francisco and Back (London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 1871), pg. 67-68.

John S. Hittell, A History of San Francisco and Incidentally of the State of California (San Francisco; Bancroft Company, 1878), pg. 380.